|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COVER STORY

Through magical realism, Salman Rushdie examines private lives, public realmsBY SHIRA J. BOSS '93

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

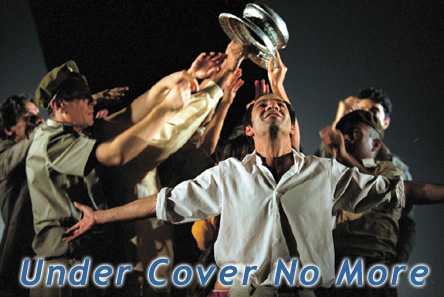

| The play stars Zubin

Varla as Saleem, whose telepathic powers allow him to communicate

with others born at the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947,

India's independence day. |

Earlier in his career, the author must have reveled in his recognition in the literary world, which came after the 1981 publication of Midnight’s Children, his second novel. It wasn’t until the dramatic controversy surrounding The Satanic Verses, his fifth novel, published in 1988, that Rushdie was shrouded with an ugly side of fame. With his distinctive outward-slanting eyebrows and domed, Garfield-like eyes, Rushdie became an international symbol, sometimes played up in caricatures making him look devilish. People asked him if he was going to apologize, and he responded, for what?

“I include Rushdie among the great novelists who we study — Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, E.M. Forster. These great novelists manage, at times, to give us insights into their civilizations that we cannot get from an historical account,” says Dennis Dalton, political science professor at Barnard.

During the 10 years following the execution order, Rushdie gradually wove himself back into the fabric of public society, and the new Iranian regime officially rescinded the order in 1998. Rushdie now lives in New York. He has continued to write novels and now has co-written Midnight’s Children as a play, and whether or not he welcomes it, his nearly iconic status is not likely to fade.

“New York is the only city in the world, since I’ve left Bombay, where I’ve actually felt normal, or at least everybody else is abnormal in the same way,” Rushdie recently stated.

Abnormalities and commonalities are a theme of Rushdie’s work. Through the genre of magical realism, the author examines how private lives intersect in public realms, and how individuals fit into history. Rushdie chose a profession rooted in solitary work, yet he has a gregarious personality and believes that to be a writer one has to “plunge into the world as far as you can.” He is a voracious movie viewer, a rock ’n’ roll fan and even a bit of a socialite. He thrives on big cities, having successively lived in and written about Bombay, London and New York.

Rushdie himself belongs to India’s generation of Midnight’s Children, who in his novel were born at the stroke of midnight on India’s independence day of August 15, 1947. Rushdie was born in Bombay two months prior to that date, and a family joke goes, “Salman was born, and two months later, the British ran away!” A Muslim by birth, Rushdie says he grew up without religion. He was raised in Bombay — a “happy, uneventful” childhood — until he was 13, when he was sent to England to attend the private Rugby School. There, he was pestered and unpopular, ostracized as a minority.

He had a better time when he got to Cambridge in the mid-’60s to study at King’s College. Majoring in history, he also began acting in the theater and spent a prodigious amount of time at the movies — so much that when he refused to cut back to concentrate on his studies, the school took away his scholarship. “I always say I got my education in the cinema,” Rushdie said. He had grown up with Indian popular movies (Bombay later became known as Bollywood), and his collegiate years coincided with a golden age of international cinema, with films from French New Wave directors and from Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray and other greats.

|

|

|

| Salman Rushdie working

during rehearsals with one of the actresses from Midnight's

Children, co-authored the stage adaptation more than

two decades after his novel was published. |

Rushdie credits the language of film with giving writers an expanded collection of expressive tools. After he saw French director Jean Luc Godard breaking cinematic rules by using jump cuts, he brought that technique into his writing. “I thought, that’s something that you could do in a book. You could go from the wide angle to the intimate very suddenly. It gave me an interest in very fast changes,” he said. “One of the things I tried to do in prose was to write in a way where the weather can change very fast — the paragraph or even the sentence can begin very comically and suddenly shift register into darkness.”

After graduating from Cambridge in 1968, Rushdie briefly moved to Pakistan, where his family had relocated. Television was just starting to take hold there, and he convinced a station to co-produce with him a version of Edward Albee’s play Zoo Story, in which Rushdie acted. It was a disaster. Besides the technical shortcomings of the studio, Rushdie tangled with censors over the play’s mention of pork. He returned to England, where he worked for a couple of years acting in London’s fringe theater. Then he turned seriously to writing, and began his first novel while supporting himself as an advertising copywriter.

“In a way, I never left. I still feel as much rooted in the East as in the West,” Rushdie said in a 1995 interview. “It simply was that I chose to make my primary home in the West, but my imagination never migrated.”

His first novel, Grimus, came out in 1975. An abstract tale about a Native American, it was panned and quickly remaindered. Even Rushdie had problems with the book, and retreated to figure out where he had gone wrong (he determined it was too abstract, too unrecognizable). Undeterred, he was soon inspired to return to his childhood roots and to write a semi-autobiographical novel, set in Bombay, that traced the birth and coming of age of post-independence India.

With the little money he had earned from Grimus, Rushdie returned to India to travel for six months. The tradition of oral storytelling particularly intrigued him. Instead of linear stories meant to keep an audience’s attention and draw them through the plot, Indian storytellers mix plot with performance art. They take breaks, detour through side stories, sing songs, tell jokes, even ad-lib political satire. Instead of being distracted, the audiences are further entertained.

|

|

|

| Saleem is swapped at

birth, and his life becomes entwined with the destinies of

the twin nations, India and Pakistan, born at the same moment

as he. |

That realization, along with Rushdie’s comfort with big cities, led him to an unorthodox way of constructing a novel: packing it in. He said he wanted to figure out how to build “the literary equivalent of a crowd.” “Our lives are constantly being bumped into,” he described, referring not just to the physical jostling of a metropolis but to the emotional and circumstantial interaction between an individual life and its surroundings. He started to write by padding a main story with other tales. “The way you keep people interested is by making it complicated,” Rushdie decided.

It took Rushdie five years to complete Midnight’s Children, and his reinvention worked. It won the 1981 Booker Prize and established Rushdie as a unique literary voice. Later, in 1993, it would be honored with the “Booker of Bookers,” the best Booker-winner of 25 years.

“Midnight’s Children is a highly cinematic novel,” says Gayatri Spivak, Avalon Professor in Humanities. “Orality contains within itself certain kinds of potential filmic elements, which the great, traditional, realistic novel does not. I think Rushdie’s novel brings these two together.”

Rushdie’s next novel, Shame, in 1983, also was a Booker finalist, as was his next five-year effort, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988. Set in London, The Satanic Verses incorporates events from the Koran and Islamic life in novelistic fashion. Some Muslims were outraged by it, calling it insulting and blasphemous.

While not referring specifically to The Satanic Verses, SIPA visiting professor Saeed Shafqat says of Rushdie, “He looks at the Muslim culture as sort of authoritarian, and thereby conveys an impression that basically reinforces the same kind of image that continues to perpetuate — or has been perpetuated by many Orientalist writers with reference to Islamic society.”

The Satanic Verses was banned in India, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which pained Rushdie even before the real trouble hit. Soon there were demonstrations complete with book burnings and picket-style signs depicting Rushdie as evil and calling for his murder.

|

|

|

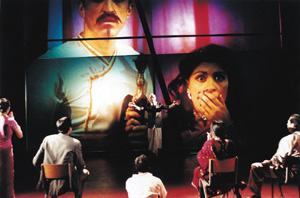

| A scene from Midnight's

Children, playing at the Apollo Theater in Harlem on

March 21-30, 2003. |

“It was clear to me that Khomeini was a very powerful man, and the danger was very real and very serious,” Rushdie said in 1995. “At the same time, I felt a sense of unreality. A large part of me felt that this is unreal and something out of a bad storybook. The world of the fatwa (religious order) seems more unreal than the world of my own fiction — that feels like real life.”

His publishers received bomb threats and death threats. His Japanese translator was stabbed to death, and his Italian translator and Norwegian publisher were attacked.

Angered and shaken, Rushdie went into hiding. Separated from his family, he was put under police protection in Britain and moved from one safe house to another for years. His secretly scheduled appearance at Columbia in 1991 was a rare public outing.

But Rushdie kept working. He was determined not to be silenced by the death threats, so he wrote daily. “One of the things I’ve always done is sit alone in a room, so now I do it even more,” he said during this period. He wrote essays, short stories and a children’s book inspired by his son, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990). Eventually, he went to work on his next novel, The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), which is largely about loss. It is also a nostalgic novel, again set in India. For the decade of the fatwa, Rushdie was denied a visa to return to India.

While Rushdie was underground, a wave of writers, journalists, artists and activists countered the threats with a show of support for him and for free speech. Paul Auster ’69 wrote an op-ed article in The New York Times describing how sad and horrifying it was as a writer to think of what happened to Rushdie. In 1993, an entire book was written about the “Rushdie affair” titled For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech, which includes a contribution by University Professor Edward Said.

His supporters, along with Rushdie, campaigned for governments to pressure Iran to remove the fatwa. The Ayatollah died shortly after issuing it in 1989, but it remained in effect.

Rushdie emerged gradually, particularly after the publication of The Moor’s Last Sigh. “My interest throughout this has been not to run and hide like some kind of rat, but to fight back like an intellectual and artist against a very unintellectual and very philistine threat,” he said when that book came out.

In September 1998, the Iranian government removed the fatwa and the ordeal, which Rushdie has called “the transforming experience of my life,” was over. The next year, he came out with The Ground Beneath Her Feet, a novel that combines the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice with rock ’n’ roll.

Rushdie makes a special effort to stay connected with popular culture; he has hung out with U2 as well as literati. “Both sides are necessary,” he said. “Homer and Homer Simpson.”

Rushdie, whose most recent novel, Fury (2001), is set in New York, says he has moved on from writing about India. But the trendiness of India makes now an opportune time for the production of Midnight’s Children as a play. He says the play resembles the free form of fringe theater in which he worked in London in the ’60s, and he feels he has come full circle by doing collaborative work again.

Shira J. Boss ’93 is a contributing writer for Columbia College Today. Her last feature was on second careers.

| || | || |

CCT Home |

|

|

CCT Masthead |