|

FEATURE

Lightweights

Earn Trip to Royal Regatta by Winning Eastern Sprints, Then Bow to

Yale

By Bill Steinman

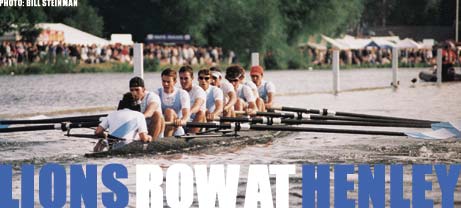

The

race course at the Henley Royal Regatta, the crown jewel of rowing,

is 2,112 meters long. To reach the starting line, crews begin from

slightly beyond the finish line and row the length of the course to

get into starting position.

Columbia’s varsity lightweight crew rowed at Henley this

summer, but began much further away than those 2,112 meters. Two

years further.

The

Lion lightweights had made this trip before, in 1998. Coming off a

second-place finish in the national championships at the IRA

Regatta, they were sent, through the generosity of supportive

alumni, to Henley, where they reached the quarterfinals of the

Temple Challenge Cup before losing to Durham University.

Every person who made that trip for Columbia wanted nothing

more than to go right back the next year, in 1999. But it

wouldn’t be easy.

“We were told that the alumni felt finishing second in

the IRA that year [was reason enough] to be sent to Henley,”

James DeFilippi ’00 recalled, “but to go back again, we

had to win something big, like the Eastern Sprints or the

IRA.”

It

was not to be. The lightweights lost their first three races, won

two cup events, then finished second to Princeton at the Eastern

Sprints. Those two crews entered the IRA as co-favorites, and while

Columbia managed to reverse its order of finish with the Tigers,

the two crews crossed the line fifth and sixth, with Harvard

winning the race. There would be no return trip to

Henley.

“It was a strange season. Nothing was predictable,”

said DeFilippi. “We were confused and disappointed by the

fifth place. I was haunted by that all this past year. But now,

looking back, we all took that as fuel to work that much

harder.”

It

worked. The varsity lightweight crew that returned last fall, and

that coaches Tom Terhaar and Dan Lewis ’94 molded through the

fall and winter months, was even more formidable than in

1999.

“We knew from the get-go we had one of the strongest

boats in the league and the nation,” said DeFilippi, now a

senior and co-captain with Ryan Ficorilli ’01. “We just

had to keep working our butts off, and make the extra effort to

learn technique. We had the power and speed, we needed the

technique.”

Columbia lost its first two races, upsets at the hands of

Georgetown and Rutgers. “We were not rowing together very

well,” said DeFilippi. “Things hadn’t come

together yet — we hadn’t jelled. To Tom

[Terhaar]’s credit, he kept our heads up and focused. We

never counted ourselves out.”

But

the Lions needed to halt the pattern that was developing. Could

they do it the next week, in the most grueling test of the regular

season, the Dodge Cup against Yale, ranked first in the nation

among varsity lightweight crews, and Penn.

It

was foggy that April morning on the New York Athletic Club’s

Orchard Beach course, and spectators couldn’t see the crews

until they were almost at the finish line. When they came into

view, Yale was in front, as expected, but Columbia was closing

fast. Very fast. In fact, although Yale held on to win, Columbia

finished just three-tenths of a second behind.

The

race signaled the beginning of collegiate rowing’s most

closely contested rivalry of 2000. It also proved, both to the

rowing world and to the Lions themselves, that Columbia was a force

to be reckoned with. “It confirmed for a lot of us that we

weren’t lying to ourselves,” said DeFilippi. “We

really were fast! We realized that if we worked, we could win.

Through the next two races, we kept our eyes on our

goals.”

Columbia beat Cornell and MIT in the Geiger Cup, then topped an

accomplished Dartmouth eight in the Subin Cup. That set the stage

for the Eastern Sprints, on Lake Quinsigamond in Worcester,

Mass.

The

Eastern coaches had seeded the team fourth, to which the Lions took

exception. “Yale had won the HYP (Harvard-Yale-Princeton)

race, so we knew we were as fast as Harvard, Yale or

Princeton,” DeFilippi said. “We didn’t expect to

win, but none of us thought that we couldn’t do it. We knew

if we were to win, though, we would have to row the race of our

lives.” Even Terhaar, their coach who never goes out on a

limb, said he “thought it was possible to win the

Sprints.”

At

many major regattas, an observer rides along the race on a motor

launch, providing a play-by-play that is broadcast to spectators

near the finish line. But right before the lightweight Grand Final,

the ship-to-shore connection went out. So after the race began,

3,000 spectators were forced to wait on edge until the leaders came

into view.

When

they did, Harvard was in front, followed by Yale. And neck-and neck

with them was Columbia.

“At 500 meters, we were even with Harvard and

Yale,” Ficorilli recalled. “In the last 400 meters, we

started sprinting. We pulled ahead of Harvard and with three

strokes to go, we were tied with Yale. We pulled ahead in the last

three strokes!”

Dean

Austin Quigley (right) enjoys a moment at Henley with Coach Tom

Terhaar.

PHOTO: BILL STEINMAN

|

The

boats crossed the finish line so close together, no one in the

crowd knew who had won. They milled nervously about, awaiting the

officials’ decision on the photo finish. On the lake, the

crews sat motionless.

“I put my head down and said a prayer,” DeFilippi

said. “We all said prayers and kind of held our breaths. Yale

was doing exactly the same.”

Finally came the announcement: “In third place with a

time of 5:55.63, Harvard.” It was met with a chorus of groans

from the Crimson fans. “In second place with a time of

5:52.59, Yale.” This elicited more groans, and a collective

gasp from the Lion faithful. Then came the cheers, almost drowning

out the announcement that for the first time since the Eastern

Sprints began in 1946, a Columbia varsity stood atop the list.

Columbia won in 5:52.48, a scant eleven-hundredths of a second

better than Yale.

Even

as the Lions were getting their medals and throwing both their

coxswain, Julia Baehr ’02, and their coach in the lake,

thoughts had turned to Henley. “We started thinking of Henley

when we put the boat in the slings after the race,” said

DeFilippi. “We can go, we thought, we’ve won a big

one.” In fact, Tom Sanford ’68 had brought a packet

containing a Henley application with him, and after the race he

slipped it to former lightweight rower Jim Weinstein ’84, who

approached Terhaar.

So

the wheels were already turning when the lightweights left

Worcester, heading directly for Dartmouth and a 10-day pre-IRA

training camp. They talked about the trip when they got to

Dartmouth, and worked on adjusting their schedules, postponing

summer jobs, classes and vacations.

“We were so excited about Henley,” DeFilippi said,

“but we had to get our minds off it and concentrate on the

national lightweight championship at the IRA in two

weeks.”

The

IRA, held on the Cooper River in Camden County, N.J., is a

three-day affair which until recently featured only heavyweight

crews. The lightweight competition takes place only on the final

day, a Saturday. The preliminary heats are the first event, usually

at about 7:30 a.m. The crews then go back to their hotels and rest

until the finals, which takes place at about 3:00 p.m.

On

the strength of its Sprints victory, Columbia entered the IRA as

the top seed. It won its qualifying heat, but got off to a slow

start in the championship race. Harvard took the early lead and

held it until the final 400 meters, when Yale pulled even and then

edged in front, with Columbia and Princeton closing fast. Those

three crews finished just six-tenths of a second apart, but it was

Yale that came in first, with Princeton second and Columbia

third.

Columbia’s rowers were disappointed to have missed the

title by so little, but they also were proud. “We had put

ourselves back into contention [after the slow start]. We

hadn’t given an inch,” DeFilippi said. “We knew

we hadn’t won, but we rowed a very, very good race.”

And Henley beckoned, just a few days later. “We started

thinking of Henley right after our race was over,” DeFilippi

said. “We knew we still could go to Henley and do very

well.”

Some

crews may approach Henley as a week-long holiday, a reward for

their hard work. Terhaar’s crews are not among them.

“It’s a carnival,” the coach said, “with a

really serious race in the middle of it.”

Columbia wasn’t there for the carnival. “We

weren’t over there to go sightseeing,” DeFilippi said.

“There wasn’t a lot of time to do anything. We

practiced twice a day. The rest of the time we watched TV, read, or

walked around the town.”

Columbia rowed in two preparatory races. In the Marlow Regatta,

the varsity eight entered two races, a 1500-meter row and a

500-yard sprint, and won them both, beating Yale in the finals of

each. A week later, Columbia rowed in the Reading Town Regatta,

also on the Thames. This time, Yale won the Elite Eight race, by a

length.

Official racing began at Henley on June 28, a Wednesday.

Columbia had been seeded — “selected” in Henley

lingo — and didn’t have to race until Thursday, against

Imperial College of London. “We were nervous before the

race,” DeFilippi said. “It was our first race at 2000

meters or more since the IRA, and we didn’t know anything

about Imperial College’s team.”

Columbia got off to a lead, Imperial caught up, then the Lions

moved out again. Suddenly Imperial’s boat began to zig-zag

across the course, finally running into a barrier on one side of

the course. By the time Imperial got going again, Columbia was well

in front and stayed there, winning “easily,” which is

rowing parlance for quite a few boat-lengths.

The

next race was on Friday against the University of Glasgow, which

had placed third in Great Britain’s national collegiate

championships. Glasgow’s rowers were larger than

Columbia’s, averaging 174 pounds to the Lions’ 161, but

Columbia had seen Glasgow row and “knew it was a race we

could win,” said DeFilippi.

Lewis, the assistant coach who rode in the umpire’s

launch, described the race as he saw it. “We had a little bit

better start, then we settled,” he said. “We were

already ahead. We put a little move on and established open water

[between us]. That was it.” Columbia crossed the finish line

for the 2112-meter course in 6:37, beating Glasgow by a comfortable

212 lengths.

In

winning its first two races, Columbia had learned not only how to

race over the Thames River course, but how to deal with the huge

crowds drawn to the spectacle that is the Henley Royal Regatta.

Over 100,000 people attended the Friday races, lining the entire

length of the course on both sides.

The

Band of the Grenadier Guards plays in the Steward's Enclosure, part

of the pagentry of Henley.

PHOTO: DAN RICHMAN '98

|

“All those people are fun, but extremely

distracting,” DeFilippi noted. “Every time you take a

stroke, there are people watching it. You get accustomed to racing

in the U.S., where the crowds gather at the end of the races. For

the first half or three-quarters of the race, it’s extremely

quiet because nobody’s on the side watching. Here you have an

audience all the way down the course.”

The

victory over Glasgow had moved Columbia into Saturday’s

quarterfinals — and another showdown with Yale. The two

schools had met six times during the season and post-season, and

each had won three times. From the moment they saw the draw, and

realized they could meet each other in the quarters, that match-up

had been on the minds of both schools’ rowers.

The

crowds had swelled, to put it mildly, by Saturday’s races.

More than 500,000 fans crowded into little Henley-on-Thames, lining

the course 50 and 60 deep in its entire length. The two Ivy League

crews, rowing slowly to the starting line, looked at the multitudes

in awe. Then the race began.

Yale

had the better start. “They led after 400 meters, then they

put on a move, which we matched,” DeFilippi said. “We

put on a move to catch them, but they matched it. All the way down

the course, they matched, we matched.”

Columbia had become known for its ability to come from behind,

but that’s very difficult at Henley, especially since heavy

rains the day before had caused a stiff current on the Thames,

flowing against the racers. “In the first 400 meters, Yale

got what they needed,” Terhaar said. “We rowed as hard

as we could. Anything we gave up early, we started to earn back.

They fought the whole way, like they fought the whole season. But

on a day like today, there was no catching up.”

Yale

swept across the finish line the winner in 6:40, with Columbia a

half-length behind. The Bulldogs went on to win its semifinal and

upset Oxford Brooks University in the finals to win the Temple

Challenge Cup.

“I’m disappointed to have lost, but we rowed a

great race, and I’m happy for Yale,” DeFilippi said as

he prepared to leave Henley.

“Yale did a great job,” Terhaar said, “and we

did a great job.”

For

the second time in three years, Columbia’s lightweights had

traveled to the crown jewel of rowing, the Henley Royal Regatta,

and had done themselves proud. There was little doubt they’d

be back.

About the

Author: Bill Steinman

is senior associate director of athletic communications, a

fixture in the athletics department for three decades and the

lifeline you want to have left if the topic is Columbia sports

trivia.

|