|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COVER STORYHome on the Heights:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Hartley Hall and the adjacent Livingston (now Wallach) Hall were the

first dormitories built on the Morningside Heights campus. When

students moved in in 1905, they found spacious lobbies with marble floors

and oak paneling. Upstairs, rooms were arranged off central corridors.

Both buildings were renovated in the 1980s and the rooms reconfigured

into suites. PHOTO: CCT FILE PHOTO |

Each fall, excitement hangs in the air as College students arrive on campus with their families, carloads of belongings in tow, ready to move into their homes for the next nine months. The day is filled with the promise of independence, new experiences and new friends. “I will always remember move-in day, maneuvering those bulky, orange moving bins from the elevator to my little slice of Columbia,” Christina Wright ’03 recalls.

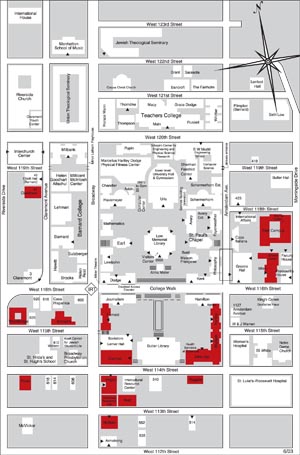

Students have partaken in this annual College rite since 1905; this fall, Columbia marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of Hartley and Wallach (formerly Livingston) Halls, the first residence halls on Morningside Heights and an important step in the creation of today’s College.

In the past century, Columbia has become a fully residential college, with 99 percent of first-years and 95 percent of upperclassmen living on campus. The College has one of the highest percentages of students living on campus in the Ivy League, a fact that defies what many people might expect of an urban school. The campus has 5,200 undergraduate beds spread across 17 residence halls bound by Riverside Drive, Morningside Drive, 113th Street and 119th Street; approximately one-quarter of the campus is used for undergraduate housing. For Dean Austin Quigley, creating a 24-hour living and learning environment has been a hallmark of his 10-year tenure. “Making Columbia College fully residential has changed its character significantly by offering new opportunities whose full exploitation still lies ahead,” he says.

MY COLUMBIA

Columbia University Development and Alumni Relations recently launched its redesigned Web site, Columbia Connection, which offers myriad alumni services and information. One popular section of the site, inspired by Ashbel Green ’50, ’52 GSAS’s book My Columbia, a collection of University alumni remembrances, allows alumni to post their Columbia memories, aptly named “My Columbia.” Following are a number of dorm-related stories that were submitted by College alumni and are printed, some in edited form, with the writers’ permission. To contribute your story, log onto My Columbia.

A REAL COLLEGIAN AT LAST

Jack Kerouac ’44

Excerpted from Vanity of Duluoz

One great move I made was to switch my dormitory room from Hartley Hall to Livingston Hall where there were no cockroaches and where b’God I had a room all to myself, on the second floor, overlooking the beautiful trees and walkways of the campus and overlooking, to my greatest delight, besides the Van Am Quadrangle, the library itself, the new one, with its stone frieze running around entire with the names engraved in stone forever: ‘Goethe ... Voltaire ... Shakespeare ... Moliere ... Dante.’ That was more like it. Lighting my fragrant pipe at 8 p.m., I’d open the pages of my homework, turn on station WQXR for the continual classical music, and sit there, in the golden glow of my lamp, in a sweater, sigh and say, ‘Well, now I’m a real collegian at last.’

|

Livingston Hall room, circa 1950 PHOTO: DANIEL KRAMER ’50E |

Columbia’s dorms have become much more than places to eat and sleep. From the halls of John Jay to the suites of East Campus, the dorms hum with the campus’ intellectual and social life. “Students get an education in the classroom at Columbia that is excellent, but they also get an education in the residence halls,” Quigley says. “What they learn from and with each other in the residence halls is every bit as important as what they learn from faculty in the classroom. The remarkable diversity of the Columbia College student community is a social and educational resource for everyone.”

|

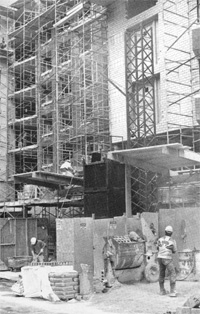

Schapiro Hall under construction, 1987 PHOTO: CCT FILE PHOTO |

The shared experience of dorm life brings people together. Tera Childs ’98 notes of her freshman year on Carman 10, “We were an eclectic group of athletes and computer geeks, East Coast sophisticates and West Coast bunnies. There were econ majors and philosophy minors. Future lawyers and future scientists. Diverse students with one thing in common: The X-Files.”

Robert Pollack ’61, the College’s dean from 1982–89, expressed the importance of the change in a New York Times article: “When you don’t live in a dormitory or fraternity, you’re not really a part of the place. You cannot be educated to think for yourself unless you are challenged by other bright young people who are trying to think for themselves. This occurs best in the environment of peers. ”

Scott Wright, head of Housing and Dining Services (formerly the University Residence Halls office), feels that the strong increase in the percentage of students wanting to live on campus in recent years is linked to four factors: improved residence hall quality, better residential programs and services, a range of campus housing options and price — living in residence halls for about $6,000 a year sure beats renting a Manhattan apartment.

Since 1988, when Schapiro Hall opened on 114th Street, the University has guaranteed four years of housing to every College and SEAS student. This has forced Columbia to increase undergraduate housing with construction of a new residence hall, renovation of existing residence halls and conversion of graduate student housing to undergraduate housing.

|

Hartley Hall cornerstone dedication, 1904 PHOTO: CCT FILE PHOTO |

|

Carman Hall under construction, 1958, with Ferris Booth Hall (the former student center) in the foreground PHOTO: CCT FILE PHOTO |

While Columbia may not have the houses of Harvard or the colleges of Yale, students may choose from a variety of accommodations including singles, doubles, suites and apartments. “Residence halls at many institutions are of a single pattern,” Quigley notes. “Our residence halls are of many kinds, allowing students to experience different kinds of living and differing ways of relating to each other that come with those living situations.”

First-years usually live in rooms on long hallways, such as in Carman and John Jay. For upperclassmen, the most sought-after housing includes suites in Hogan, East Campus, River, Woodbridge and Watt, where rooms are clustered around a common room and kitchen. The annual April housing lottery is a time of anxiety, prayer, celebration and disappointment as students vie for the best housing and negotiate roommates. A spring 2003 Spectator headline captured it best: “Tales of Joy, Worries of Wien After URH Lotto.”

Lucky first-years in the coveted upper-floor, campus-side rooms of John Jay and Carman have stunning views of Low Library and northern Manhattan. During his stay at Columbia in the 1930s, Spanish poet Frederico Garcia Lorca wrote, “My room in John Jay is wonderful. It is on the 12th floor of the dormitory, and I can see all the university buildings, the Hudson River and a distant vista of white and pink skyscrapers. On the right, spanning the horizon, is a great bridge under construction, of incredible grace and strength.” Residents of East Campus wake to the sun rising over Central Park and Harlem.

|

East Campus under construction, 1979 PHOTO: HERMAN BERNSTEIN ASSOCIATES/COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, COLUMBIANA LIBRARY |

|

Johnson (now Wien) Hall under construction, 1923 PHOTO: COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, COLUMBIANA LIBRARY |

Primarily clustered around the southern portion of campus, residence hall living puts almost the entire undergraduate student body in close proximity, allowing students to interact constantly and to roll out of bed and into their first class in minutes. Butler Library, Dodge Fitness Center and other campus facilities are minutes away, as are the subway and restaurants and shops of Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue

Yet, much of the College’s extracurricular action takes place right in the residence halls, and seemingly every Columbia alumnus can tell you where he or she lived — often right down to the room number — and will happily revisit those times. Some of this is due to the intellectual and social vitality of life in the residence halls, where students from diverse backgrounds are living away from home for the first time. It also may have to do with the fun and mischief that students find in the residence halls, from indoor football and cricket games to parties (sanctioned and unsanctioned) to memorable pranks and stunts. Perhaps the most legendary are the regular attempts to pack all of a floor’s residents into a John Jay elevator.

As dorm life has evolved, many features from yesteryear have disappeared, including daily maid service, dorm mail rooms (Alfred Lerner Hall, the student center, now is the mail center for all undergraduates), door-to-door laundry service and the campus tailor shop, along with the popular Furnald Pub (which many alumni still ask students about, though it is long closed) and rules about female visitors.

PANTY RAID

E. Michael Geiger O.D. ’58

It was a warm, beautiful, late-spring day, and we were studying for finals. As I looked out of my Livingston Hall second floor window, a pretty co-ed walking by caught my eye. I yelled a hello to her. Then someone at another window shouted something. Then someone on the campus shouted something back. Soon there were students at many windows in Livingston and John Jay shouting to the mob of students that had gathered on the campus and were shouting back. I yelled “panty raid” and hundreds (it seemed) of us rushed to the Barnard dorms. I got in the gate, but the police were there almost immediately and blocked the entrance. When asked what I was doing there I said that I had a date. Fortunately, the Barnard gal who was my “date” backed me up and all ended well ... except no panties.

WATER IN THE DORM

Stanley Futterman ’61, P’89

At the beginning of February 1958, the start of my second semester at Columbia, a bed became available in a three-bed attic room on the 10th floor of Hartley and I bid adieu to my hour-and-a-half commute from the far reaches of East Flatbush. My roommates were a senior chemistry major who was an All-American fencer from Queens and a junior Fulbright scholar from Sweden. The adjoining rooms at the north end of the corridor were occupied by two junior-year track and field athletes and a freshman/ sophomore pair from Sigma Alpha Mu, respectively.

One evening, returning late from putting Spectator to bed (perhaps), I noticed the track athletes gleefully tilting a wastebasket filled with water against the Sammies’ door. Having by then learned something about justice from CC, I returned to the scene a few minutes later and transferred the wastebasket to the perpetrators’ door. Unfortunately, a small sound resulted from the waste basket’s front tip kissing the door. I hurried back to my room and thought I was safely inside when I heard the sound of water falling and multiple expletives resounding in the hall. Soon the athletes appeared at my door.

Oblivious to my invocation of the Fifth Amendment, they carried me to the showers where, fully clothed, I got a dose of their (and my) medicine. It was worth it.

For many alumni, today’s residence halls seem cushier, with unimaginable amenities and fewer rules. Residence halls, like the College, are coed. All rooms come with telephones, high-speed Internet connections and floor or suite lounges, as well as kitchen access. Five residence halls have central air conditioning, and others have room air conditions. Singles average 125 square feet and doubles 210 square feet, and Columbia can boast of having one of the Ivy League’s highest percentages of singles.

With most of its students living at home well into the 20th century, Columbia was long considered the day school of the Ivy League. As Barnard Professor Robert McCaughey writes in Stand, Columbia, “The experience of a 19th-century Columbia student was a commuter’s experience rather than a residential one, and not all that life-altering, given the continuing impact of family life and the competing attractions of New York City.”

|

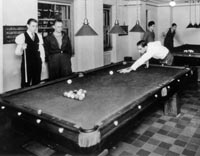

Hartley Hall once featured a game room with pool tables. PHOTO: A. TENNYSON BEALS/COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, COLUMBIANA LIBRARY |

When classes began on Morningside Heights in 1897, it was a barren section of northern Manhattan. Most students and faculty lived downtown and rode to campus on the elevated trains or streetcars until the IRT came to 116th Street in 1904. Even before the move to Morningside Heights from Midtown, many members of the Columbia community, especially alumni, dreamed of creating a residential environment on campus to develop “college spirit.”

The new campus made this dream a possibility. As Barry Bergdoll wrote in Mastering McKim’s Plan: Columbia’s First Century on Morningside Heights, “Dormitories, which were frequently a focus of alumni giving on many campuses, became the rallying cry of those who sought to reinforce the college tradition as opposed to those who felt that a university should take little interest in students’ lives outside the classroom.”

Seth Low, Columbia’s president from 1890–1901, adamantly opposed dormitories, believing that Columbia students should live throughout the New York area, making Columbia truly a university of the city, like the great German universities. Low attempted to keep dormitories the growing university’s last priority, urging alumni to construct private dormitories elsewhere on Morningside Heights.

Two important developments spurred the construction of Columbia’s first residence halls: the election of Nicholas Murray Butler (Class of 1882) as Columbia’s president in 1902 and the graduation of Marcellus Hartley Dodge (Class of 1903). Butler brought a new focus on student life and longed to attract students from outside the New York area. “As you know, it is very difficult for the students, graduates or faculty to urge boys from good families from outside New York to come to Columbia College when there is no place in which they may get suitable board,” Dean Herbert Hawkes wrote to Butler. “Until this is provided, it will be difficult to attract, and still more difficult to retain, the kind of student we desire.”

NU? HALL

Arthur Bernstein ’64

In those glorious days of yesteryear, when New Hall was unfinanced and therefore unnamed, women were prohibited from the dorm. Surprisingly, this even applied to Vassar women, as I discovered one rainy day when I smuggled such contraband into my room. Bad smuggling when wet footprints lead to your closet, which is where our floor counselor discovered the body — quite alive and embarrassed— when he flung back the door.

|

John Jay Hall room PHOTO: A. TENNYSON BEALS/COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, COLUMBIANA LIBRARY |

A PERFECT MATCH

Adam Bender ’64, ’68 P&S

In 1960, Carman Hall had just opened and still was known as New Hall. The College and the dormitories were all-male and unchaperoned women were not allowed in the rooms.

In the early 1960s, a new rule took effect that was considered very progressive at the time. During certain daylight hours, women were actually allowed to come into our rooms unchaperoned, on one condition: There had to be “a book in the door” to keep it open. The dean assumed that such a threat of exposure would prevent us gentlemen from taking too many liberties with our lady guests.

Being the clever and literate Men of Morningside that we were, we decided to interpret the definition of “book” very liberally. We opened a match book and pushed the cover between the doorpost and the closed door — and the rest is history!

SURF’S UP IN HARTLEY

Arthur Mehmel ’72, ’76 Bus.

We formed a terrific group of friends in Hartley Hall in 1968, a time when we slept on bunk beds, doors had to be open when a girl was in the room, and the hallway floors were uncarpeted tiles. One night, we got the bright idea to wet down the long hallway with soapy water. We ran and slid, like surfing, as far as we could. The winner slid so far that his lead arm went through the glass door at the end of the hallway. We spent the rest of that night at St. Luke’s Hospital, where he was getting stitches.

Dodge, who had been active in campus life, had become one of the wealthiest men in America when his grandfather, Marcellus Hartley, the owner of Remington Arms, passed away during his sophomore year. Shortly after his graduation, Dodge and his aunt, Helen Hartley Jenkins, decided to build a memorial to Marcellus Hartley with a $300,000 gift to fund the construction of Columbia’s first residence hall on the Morningside Heights campus. Dodge hoped for “the commencement of a true dormitory system … By the laying out of appropriate grounds in front of both these dormitories, South Field will at once have the character of a genuine College campus.”

When the first students moved into Hartley and Livingston in fall 1905, they were greeted by gracious lobbies with oak paneling, marble floors and enormous fireplaces. Upstairs, rooms of various sizes were arranged along a central corridor, housing about 200 students in comfortable but sparse quarters. Dances, teas with professors and other social events took place in the lounges, although there was no dining hall. Rooms were quite a bit more expensive than living in a rooming house (an average of $3.30 a week, or $129 for the academic year), and Butler noted at the opening of the buildings that “in the interest of true democracy,” rooms were arranged so as to permit “the poorer student to live in the same building and the same entry with him who is better off, and so avoids the chasm between rich and poor living in separate buildings, of which there is so much complaint at Harvard.”

While Hartley, Livingston and later Furnald (1913) put students physically at the center of College life, only a fraction of the student body could be housed on campus. By the end of World War I, there was a long waiting list of students wanting campus rooms. Rising neighborhood rents were expensive, and with roughly one-quarter of the College’s students coming from outside the New York area, the construction of additional housing was needed. The result was John Jay Hall, one of the University’s last commissions executed by the architecture firm of McKim, Meade & White.

|

The classically appointed John Jay lounge, seen here in 1959, continues to be a popular campus gathering place. PHOTO: OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS/COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES, COLUMBIANA LIBRARY |

By the time planning for John Jay began in the early 1920s, Butler envisioned a new type of dormitory that would, as he put it in his 1919 annual report, “make provision for student life and student organizations which are so important a part of the total educational influence that the university, and particularly the College, exerts.” Able to house 468 students, John Jay opened in 1927 as the new center of undergraduate life. In addition to a gracious dining hall, John Jay’s first two floors featured an impressive lounge, the popular Lions Den grill and meeting rooms and offices for student groups such as Spectator and Jester, as well as for coaches and student life administrators. Thomas Merton ’38 recalls in The Seven Storey Mountain, “The fourth floor of John Jay Hall was the place where all the offices of the student publications, the Glee Club and the Student Board and all the rest were to be found. It was the noisiest and most agitated part of campus.”

FURNALD SNOWBALL FIGHT

Robert Muirhead ’78

If I’m not mistaken, it was one of the President’s holidays in February of my senior year. I was the eighth floor residence counselor with a room right across from the TV room. Trying to grind out a paper for Professor Harris’ Tax Policy class, I heard the escalating voices of some of my residents. Not needing the distraction, I emerged from my room looking to lay down the law. Turned out some of the guys had been looking out the (open) lounge window and knocked some snow onto some of Floor 7’s finest, who were similarly poised out their window just below. Some good-natured bantering was going on, but I called a halt to the proceedings, fearing escalation. Not two minutes later, the counselor from 7, a delightful young Barnard woman, appeared in our lounge doorway suggesting there would be hell to pay over “my” charges’ doings. Then, with a grin, she popped me with a large snowball hidden behind her back. Of course, the war was on!

Quickly exhausting our ready supply of snow from the window sills, things looked bleak as the demons from the seventh floor pummeled us with a box full of snowballs. Worse, they commandeered the elevator and guarded the stairs so none could get by to open a supply route. In a moment of serendipity, I recalled having the key to the service elevator, made available to me for what reason I could not now tell you. A large contingent made its way down to the snow field in front of the dorm, loaded up to the hilt and made a charge befitting the Royal Fusiliers, bolting from the service lift screaming at the top of our lungs. By the time truce was called, both floors looked more like ski runs than Ivy League housing.

|

A dorm room circa 1965 PHOTO: DAVID PLOWDEN/ CCT FILE PHOTO |

CARMAN’S WALL OF SOUND

Saul Fisher ’86

As a freshman member of Columbia College’s last class to be admitted as an all-male cohort (women transfers graduated with us), we who lived in Carman Hall were likely also the last to experience a certain male nocturnal ritual. Almost every weekday night, around 11 p.m., a growing, groaning whelp could be heard coming out of one of the windows on the north facade of the building. Slightly rising in pitch and slowly growing in volume, one after another voice would join in until an enormous, sad howl echoed across the campus. The Carman wall of sound would last some three or four minutes — a seeming eternity of young, male angst — before dying into the night. Thus, I suspect, many of us first learned one of the salient differences (of that era) between Columbia and Barnard.

Although John Jay served as the social center of campus, hosting dances, alumni reunions and the traditional Yule Log Ceremony, the building gained early notoriety when The New York Times reported “Stair-climbing Stirs Columbia Students” as the elevators in the new “Skyscraper Dorm” rarely worked and students were assigned to unfinished rooms. One unhappy resident wrote on the elevator door, “A fellow dropped dead from old age waiting for this elevator,” a refrain offered by many generations of John Jay residents.

During both World Wars, Columbia’s residence halls were pressed into service to house thousands of recruits enrolled in training courses. During World War II, midshipmen lived in John Jay, Hartley, Livingston and Furnald as Columbia turned out “90-day wonders.” Dorm rooms at Columbia have never been so clean; commanding officers inspected daily with white gloves for signs of dust and dirt, and beds had to be made with military corners.

In the wake of World War II, Columbia’s enrollment reached new highs as veterans flocked to campus. By 1948, the College was housing 35 percent of students on campus and still not meeting the housing demand. Overcrowding led to unpleasant conditions, and in the 1950s, planning began for a new residence to be financed with a $3 million loan from the Federal Housing and Home Agency.

In 1959, New Hall, later renamed Carman Hall after Dean Harry Carman, opened to undergraduates. Never mistaken for an architectural masterpiece, Carman’s cinderblock walls and bland façade made little reference to the classical campus. Architecture critic Allan Temko ’47 noted that Carman’s long hallways and pattern of two double rooms with a shared bath called to mind a “Victorian reformatory,” and its lounge was described as “a bus station with Muzak.”

The 1960s brought change to College living as rules were liberalized, more diverse students arrived on campus and new student groups were formed, many in the residence halls. “In spring 1963, when I was in the Class of 1924 Prize Room in Hartley Hall, the College began a new regime,” recalls Eric Foner ’63, Dewitt Clinton Professor of History. “We were allowed to have a female visitor in our rooms on Sunday afternoons, from 2–4, I believe, so long as the door was propped open with a book.” Under pressure from the Undergraduate Dormitory Council, rules on visits from women disappeared in 1968.

By the late 1960s, however, Columbia’s residence halls had reached a low point. Financial difficulties made regular maintenance a low priority and students often were doubled up in rooms meant for one. Little attention was paid to residence hall programming or community life, and amenities such as common rooms and advisers were in short supply. The Cox Commission report on the riots of 1968 went so far as to say that space in the residence halls was “appallingly restricted … Naked light bulbs in corridors, scarred and battered furniture, walls and floors give the older dormitories the general atmosphere of a run-down room house … .”

In response, the University began an ambitious project to renovate and expand its undergraduate residence. By 1970, The New York Times was writing, “At Columbia, the rooms into which two students crowded are now singles, there are new television lounges on most dormitory floors, there is new furniture everywhere and, since last year, each room has its own telephone.” By 1977, plans were in motion to renovate Hartley, Livingston, Furnald and John Jay and to construct East Campus, at a cost of $20 million.

By 1980, the College was well on its way to creating a fully residential campus, with approximately 61 percent of students living in dorms. The East Campus residence hall opened in 1981, adding 723 rooms in duplex and townhouse layouts. Today, East Campus is a popular residence hall for upperclassmen; in its 2004 guide to housing, Spectator suggested, “As the capital of suite-style living for Columbia students, East Campus is home to many of Columbia’s finest (and most tasteful) parties … .”

As the College was going coed in the 1980s, Hartley and Livingston (the latter renamed in honor of Ira Wallach ’29) were renovated and planning began for another new residence hall. The 1988 completion of Schapiro Hall — made possible by a $5 million donation from Morris Schapiro ’23 — was a milestone because it allowed the College, for the first time, to guarantee housing for four years. With Schapiro Hall’s opening, The New York Times proclaimed “New Dorm at Columbia Means Diversity,” noting that Schapiro’s opening “symbolizes the completion of a dream, a national student body” for Columbia.

|

Hartley, Wallach and John Jay today PHOTO: LAURA BUTCHY ’04 SOA |

By the mid-1990s, undergraduate admissions began a sharp climb. Columbia and New York City were in demand, and planning began for a new residence hall at Broadway and 113th Street, linked to Hogan Hall by a common lobby. Designed by award-winning architect Robert A.M. Stern ’61, Broadway Hall’s pre-war style features a gracious, wood-paneled lobby that echoes detailing of Columbia’s McKim, Meade & White buildings along with great views, penthouse study lounges and many singles. Simultaneously, River Hall (on 114th Street near Riverside Drive) was closed for a year and completely renovated, turning it into a popular senior residence due to its 10-person suites of singles around kitchens and common rooms.

FURNALD FUN

Elizabeth Olesh ’95

Who doesn’t have a story about the dorms? I remember trekking up all those flights of stairs in my Columbia boxers to move into Carman 13, the band that practiced down the hall and only seemed to know “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” suitemate drama, and much more. If I were only to share one experience, though, it would be the story of senior year in Furnald.

We learned that the building was about to be gutted and renovated, so many of us took the opportunity to paint or write on the walls: my favorite decorating scheme was that of the woman down the hall, a comp lit major, who covered her walls with Baudelaire’s poems. The kitchens in the lounges were probably one step away from being condemned, and you really didn’t want to walk down the halls barefoot, but I think everyone loved living there.

I still remember finishing up my very last undergraduate paper in that less-than-desirable room, sometime late at night or very early in the morning, and looking out the window to watch life pass by on Broadway, wondering what would come next.

JOHN JAY ALLEGIANCE

Christina Wright ’03

I will always remember move-in day, maneuvering those bulky, orange moving bins from the elevator to my little slice of Columbia on John Jay 11, room 1127 to be exact. My mother quickly got over the shock of my impending co-ed living quarters and helped me make the best of what some might consider a walk-in closet. But I loved my John Jay room. I quickly made a best friend out of my next-door neighbor, Robert Rosen ’03, and we remain close friends. I suppose there was something about those tight living quarters that created an indestructible bond. Whether we were reading Cervantes or watching Dawson’s Creek, memorizing Mozart for Music Hum or preparing for a night at The West End, cramming 15 people into one John Jay elevator or spending hours in the dining hall, lasting friendships were made within those John Jay walls. Even now, two years post-graduation, I associate classmates with which John Jay floor they resided on, their Columbia origins. My closest friends were made in John Jay and I will always look back on those days with fondness.

|

An East Campus dorm room today PHOTO: SEI-WOOK KIM ’07E |

In the last decade, more than just the physical fabric of the residence halls has been updated. “By being clustered around South Field,” says Quigley, “first-year students build from the outset a sense of belonging to a class and a sense of class identity that will serve them well not just during their student years but also during their decades as alumni.” As Tricia Beckles ’01, former president of the Undergraduate Housing Council, notes, “The same people you met on your floor in John Jay are who you’re still hanging out with your senior year.”

|

Furnald lobby, 1988 PHOTO: CCT FILE PHOTO |

Quigley, along with Dean of Student Affairs Chris Colombo, also oversaw the creation of the Living and Learning Center, a housing option that opened in 2001 in which students can create programs and events for their peers. Housed in Hartley and Wallach, it has been successful and applications to participate in the program have soared. As Gerald Sherwin ’55, former president of the Alumni Association, notes, “It all takes place in the Living and Learning Center, where alumni meet with groups of students to discuss issues of the day.”

Social and intellectual events, organized by RAs, student life staff, residents and the Undergraduate Housing Council, now are a regular part of dorm life. From floor trips to Chinatown to dorm-wide chili cook-offs, and casino nights to lectures and alumni dinners, residents are provided with a constant range of events from which to choose. Faculty live in apartments in Schapiro, Hartley, East Campus and Broadway and host a variety of events. Special interest houses bring together students with similar interests, ranging in recent years from a Pan-African House to an Irish House, a Music House and a Queer House.

Most importantly, according to Quigley, is the fact that residential programs, particularly those at the Living and Learning Center, serve to extend affinity groups and establish small communities. “Rather than being brought together for one event,” he noted, “the same people come back again and again, and contacts and relationships get built on a deeper level.”

New amenities, such as game rooms, computer lounges and printing facilities, are being added to dormitories. In summer 2005, Housing and Dining Services, working with the Athletics Department, installed fitness centers in unused East Campus lounges, adding convenience to students’ lives while relieving some pressure on the Dodge gym facilities.

Despite improvements during the past two decades, much remains to be done. Several residence halls, most notably Wien, Ruggles and McBain, are overdue for major renovations, as any current student who did not fare well in the lottery will note. Wien’s tile floors, thin doors, coed bathrooms and lack of common rooms make it one of the least desirable places to live on campus; it is the perpetual butt of Varsity Show jokes.

The lack of extra housing makes it difficult to close any building for the year that would be required for complete renovation. While administrators look for a solution, incremental renovations to nearly every residence hall are made each summer. A number of smaller projects, including renovations in McBain, will add some rooms to the housing stock.

Perhaps the most exciting project on the horizon is the potential renovation of the lower floors of John Jay if Health Services moves elsewhere. Plans include additional rooms on the third and fourth floors and a historic renovation of the John Jay Dining Hall, lounge and lobby, returning them to their original splendor and providing the kitchen facilities needed to bring dining hall fare into the 21st century.

The evolution of the College into a residential school has been an important factor in its increasing popularity during the past two decades. Though there constantly is work to be done physically and programmatically, the residential experience is an important component of a Columbia education.

Michael Foss ’03 was president of the Undergraduate Housing Council and chaired the 2003 Senior Fund. He spent his first year on John Jay 13 and later lived in Schapiro, Wien, Broadway and River Halls before venturing into the real world, where housing is not guaranteed. He works at the Rosen Consulting Group.

A Look at Columbia’s Residence Halls

Who lives here: 231 students, all classes

Layout: Varied suites

Special features: Living and Learning Center; professor in residence; library; kosher deli; main lounge with piano Namesake: Marcellus Hartley, grandfather of Marcellus Hartley Dodge (Class of 1903)

History: Built in 1904, oldest campus residence hall; renovated in the 1970s and 1980s to create duplex suites in place of corridor-style layout; Living and Learning Center added in 2001 to Hartley and Wallach to increase programming and resident interaction

Who lives here: 237 students, all classes

Layout: Varied suites

Special features: Living and Learning Center; Housing and Dining Offices; wall-to-wall carpeting; main lounge with piano; study room

Namesake: Robert Livingston (Class of 1765), later, Ira D. Wallach ’29

History: Named Livingston when it was built; McKim, Meade & White design; renovated with Hartley

|

Furnald Hall PHOTOS: LAURA BUTCHY ’04 SOA |

Who lives here: 234 first-years and sophomores

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

Special features: Original oak-paneled lounge; Sophomore Class Center

Namesake: Royal Blacker Furnald (Class of 1902)

History: Renovated in 1995–96 to become part of the first-year housing complex around South Field

Who lives here: 470 first-years

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

|

John Jay Hall |

Special features: John Jay Dining Hall; JJ’s Place (originally the Lions Den); Columbia University Health Services (previously student activities rooms and private dining rooms); original detailing and lounge

Namesake: John Jay (Class of 1764)

History: The last residence hall designed by McKim, Meade & White; opened in 1929 without elevator service; designed to serve as a center for student life and activities with offices for student groups and publications

Who lives here: 572 first-years

Layout: Four-person suites

Special features: Residential Life Office; spacious main lounge with large screen TV, DVD, VCR; study room/library

Namesake: Harry Carman, Columbia College dean, 1943–50

History: Previously named New Hall, renamed in honor of the retiring dean; built at the same time as Ferris Booth Hall

|

Carman Hall, with Lerner Hall in foreground |

Who lives here: 338 sophomores and juniors

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

Special features: Original detailing; wall-to-wall carpeting; meeting rooms; lounges

Namesake: Columbia constitutional law Professor Howard Lee McBain

History: Built as the Yorkshire Hotel in 1908; converted to a residence hall in 1964; undergoing renovations 2005-06 to install new lounges and kitchens

Who lives here: 192 sophomores, juniors and seniors

Layout: Doubles and singles in suites

Special features: Original detailing; renovated lobby; wall-to-wall carpeting

Namesake: Former Columbia trustee Samuel Ruggles

History: Built as the Arizona Hotel, converted to a residence hall in 1964

Who lives here: 129 juniors and seniors

Layout: 10- and 12-person suites

Special features: Lounges in suites; spacious main lounge

History: Converted from an apartment building in 1970; gut renovated in 2000–01

Who lives here: 396 sophomores and juniors

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

Special features: Food court and lounge on ground floor, views of President’s House and Harlem

Namesake: Samuel Johnson, later, Lawrence Wien ’25

History: Built as Johnson Hall in 1924 for graduate students, converted to an undergraduate residence in the 1970s; first residence hall to house female SEAS undergraduates

Who lives here: 742 sophomores, juniors and seniors

Layout: Multi-level suites of singles and doubles

Special features: Great views, courtyard, professor in residence; houses many special interest groups, fraternities and sororities

History: Renovated in 1991, townhouse renovations in 2003

Who lives here: 417 sophomores and juniors

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

Special features: Penthouse study lounge; black box theater

Namesake: Morris Schapiro ’25

History: Originally a first-year residence hall

Who lives here: 114 seniors

Layout: Varied suites

Special features: Lounges in suites; large main lounge

Namesake: Former Columbia trustee Frank Hogan ’24

History: Built in 1898 as a nursing home; converted to a graduate residence hall in 1977; after becoming an undergraduate residence hall in 1994, became the most popular location for seniors due to its large rooms, suite layouts and location; shared lobby with Broadway Hall on 114th Street

Who lives here: 162 juniors and seniors

Layout: One-bedroom apartments

Special features: Views of Riverside Park and Hudson River

Namesake: Columbia philosophy professor Fredrick Woodbridge

History: Built in 1900 as Columbia Court; the University acquired it as a graduate residence in 1957; became an undergraduate residence in 1994

Who lives here: 123 sophomores, juniors and seniors

Layout: Varied suites

Special features: hardwood floors

History: Converted to a graduate residence in the 1970s; became an undergraduate residence in 1994

Who lives here: 143 sophomores, juniors, seniors

Layout: Studio, 1- and 2-bedroom apartments

Special features: Hardwood floors; on-floor laundry rooms

History: Built in 1908 as Clearmont Court apartments, converted to a graduate student residence in 1977; became an undergraduate residence hall in 1995

Who lives here: 371 sophomores, juniors and seniors

Layout: Corridor-style, singles and doubles

Special features: Senior class center; penthouse study lounges; wood paneling; computer lab; shares lobby with Hogan on 114th Street

History: Designed by architect Robert A.M. Stern ’60; cost $55 million

|

Broadway Hall includes a branch of the New York Public Library and retail stores. |

Who lives here: 143 undergraduates, graduate and GS students

Layout: Doubles and singles in suites

Special features: Hardwood floors, large first-floor lounge

History: Built in 1898 as Allerton apartments, converted to graduate student housing in the 1970s; 2003 housing shortage caused conversion of half of the building to undergraduate residences

| || | || |

CCT Home |

|

|

CCT Masthead |