Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

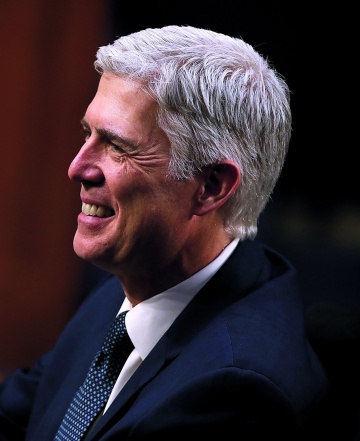

“A Republic, If You Can Keep It,” by Neil M. Gorsuch ’88

© Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

Now, as the 101st associate justice to the nation’s highest court, Gorsuch is offering his writing for broader view. His new book, A Republic, If You Can Keep It (Crown Forum, $30) mixes personal reflections with past speeches, essays and court opinions. The book offers insights into his judicial philosophy, though Gorsuch emphasizes it is neither academic in nature nor encyclopedic in its approach to the law. Rather, “it is intended for citizens interested in introductory and personal reflections on our Constitution, its separation of powers, and some of the challenges we face in preserving and protecting our republic today.”

In the following excerpt, Gorsuch introduces his view of the Constitution and the judge’s role within that framework.

F

Our founders knew that the surest protections of human freedom and the rule of law come not from written assurances of liberty but from sound structures. As James Madison put it, men are not angels and the value of their promises depends on structures to enforce them. To protect the rights of the people, the founders designed a Constitution that cedes to the central government only certain limited and enumerated powers that are, in turn, carefully separated and balanced. To the people’s representatives in Congress, the framers gave the power to make new laws restricting liberty—but at the same time they insisted that our representatives follow a deliberate and difficult process designed to achieve broad consensus before any new law might emerge. To ensure that the laws able to survive this careful process are vigorously enforced, the framers gave the power to execute the law to a single president rather than trust management-by-committee—but they also sought to ensure that the president could never arrogate the power to make laws or judge persons under them. Finally, to guarantee that all persons, regardless of their popularity or prestige, would enjoy the benefit of the laws when disputes arise, the framers created an independent judiciary—but they insisted, too, that judges insulated from democratic processes must have no role in lawmaking and should be counterbalanced with juries composed of the people.

In all these ways, the framers recognized that each branch had not only a virtue to offer but also a vice to guard against. When this design is respected, liberty is protected and the rule of law advanced. But when the executive or judiciary claims the power to write new legislation, or when the legislature or executive assumes the power to adjudicate cases, or when some other blurring of the lines occurs, liberty and the rule of law are placed at risk. Nor are these hypothetical worries or problems of the distant past. Later in the book, I share some everyday cases I encountered in my time as a judge where overlooking the structural protections of our Constitution had profound consequences for real people in our own time.

The design of our founders doesn’t just disperse power; it also has implications for how power should be exercised in each branch. Take the judicial branch. When it comes to the business of judging, our separation of powers makes clear that a judge’s task is not to pursue his own policy vision for the country, whether in the name of some political creed, social science theory, or any other consideration extrinsic to the law. Nor is it to pretend to represent (or bend to) popular will. The task of making new legislation is assigned elsewhere. As Alexander Hamilton put it, a judge’s job is to exercise “merely judgment,” not “FORCE [or] WILL.” A judge should apply the Constitution or a congressional statute as it is, not as he thinks it should be.

How is a judge to go about that job? For me, respect for the separation of powers implies originalism in the application of the Constitution and textualism in the interpretation of statutes. These tools have served as the dominant methods for interpreting legal texts for most of our history—and for good reason. Each seeks to ensure that judges honor the law as adopted by the people’s representatives, and each offers neutral (nonpolitical, nonpersonal) principles for judges to follow to ascertain its meaning. Rather than guess about unspoken purposes hidden in the hearts of legislators or rework the law to meet the judge’s estimation of what an “evolving” or “maturing” society should look like, an originalist and a textualist will study dictionary definitions, rules of grammar, and the historical context, all to determine what the law meant to the people when their representatives adopted it.

Now, sticking to the law’s original meaning doesn’t always make a judge popular or majorities happy. There are times when a faithful application of the law means that a friendless party will win and the sympathetic side will lose. That can be a hard thing for many people to swallow, and a hard thing for a judge too. But sticking to the law’s terms is the very reason we have independent judges: not to favor certain groups or guarantee particular outcomes, but to ensure that all persons enjoy the benefit of equal treatment under existing law as adopted by the people and their representatives.

Still, this tells only half the story. While our constitutional republic may be the greatest the world has known, that is no license to ignore its shortcomings. Some I’ve alluded to already and many are discussed in the chapters that follow. What happens to our experiment in self-government when we have such difficulty talking with and learning from one another in civil discussion? How can a self-governing people rule themselves if so many do not understand how our government works or the limits on its powers? How can we expect our own rights to be protected if we are not willing to respect the rights of others in return?

For judges and lawyers there are other questions, too, that maybe hit even closer to home. Why is it that cases in our civil justice system today drag on for so long, and the fees pile up so high, that many people cannot afford to bring good claims to court and others are forced to settle bad ones? How is it that in our criminal justice system the laws have grown so numerous that a prosecutor can often enough choose his defendant first and find the crime later? Over the years, I’ve worked on and written about challenges like these. I don’t begin to claim to have all the answers, but I am sure we cannot ignore the questions.

These days I sometimes find myself thinking back a quarter century to a day when, as a law clerk, I was walking with my boss, Justice Byron White, along the ground-floor hallway of the Supreme Court. As we passed portrait after portrait of former justices, he asked me how many of them I could name. As much as I wanted to impress the boss, I admitted the answer was about half. The justice surprised me when he said, “Me too. We’ll all be forgotten soon enough.”

At the time, I didn’t realize what he was telling me. Justice White was not just one of the most famous men of his day but one of the most impressive. He was a World War II hero. The highest-paid professional football player of his day. A Rhodes Scholar. Before joining the bench, he served as John Kennedy’s deputy attorney general and helped desegregate southern schools. He never cared a fig when others criticized him—as many did, harshly and often, sometimes for supposedly “straying” from results they expected of him, and at other times for doing exactly what they knew he would do. How could anyone forget him? It seemed to me impossible.

Justice White’s portrait now hangs in the hallway with the others. Every time I walk by I see visitors standing before it wondering who he was. The truth is, Justice White was right and we are all forgotten soon enough. But with the passage of time I’ve come to see that this is exactly as it should be. In our conversation all those years ago, Justice White wasn’t so much lamenting a loss as speaking a truth he warmly embraced. He knew that joy in life comes from something greater than satisfying our own needs and wants. That this raucous republic is among history’s greatest experiments. And that, at the end of it all, the most any of us who believe in its cause can hope for is that we have done, each in our own small ways, what we could in its service.

Excerpt adapted from A REPUBLIC, IF YOU CAN KEEP IT © 2019 by Neil M. Gorsuch. Published by Crown Forum, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.