Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The Doctor Whose Diagnosis Influenced Presidential History

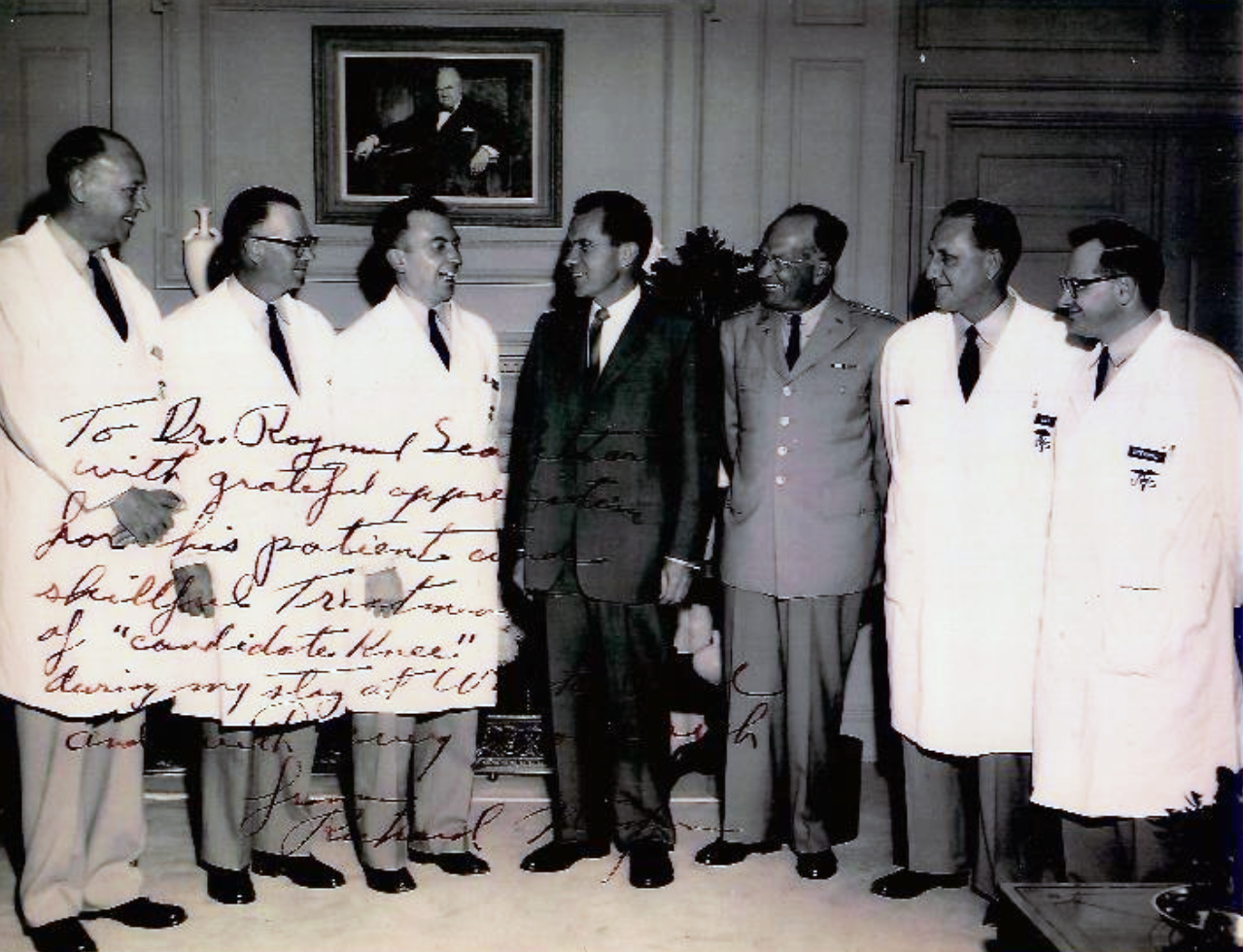

Dr. Raymond Scalettar ’50 (third from left) in an autographed photo with Vice President Richard M. Nixon and doctors at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

He was a young captain at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, late in summer 1960, when, one Saturday morning, a colonel told him to check on a VIP patient who had just arrived in the ER. The captain, recently appointed to head the hospital’s new rheumatology department, followed orders. The doctor found the patient, Vice President Richard M. Nixon, lying on a gurney.

Nixon was days away from launching a two-month campaign blitz in hopes of winning the presidency over rival John F. Kennedy. But he had an infected left knee, he was feverish and in pain, and he was about to come up against a force — the young captain, Dr. Raymond Scalettar ’50 — as resolute as his Democratic challenger.

Two weeks earlier, Nixon had torn the skin over his knee on a car door. “By the time we saw him he had a red-hot swollen joint,” recalls Scalettar, 95, who was 32 at the time. The doctor ordered a bacteria culture test; it would take two days for the result. Nixon left the Washington, D.C., hospital, expecting soon to be back on the campaign trail. Scalettar’s diagnosis upended those designs.

On Monday, the doctor learned that Nixon had hemolytic Staphylococcus aureus, an infection that, if not properly treated, could lead to blood poisoning. “Bad stuff,” Scalettar now puts it, 60-plus years since the events. He was similarly blunt with the VP. Scalettar called Nixon with instructions to return to the hospital immediately. Nixon and his aides balked; they had an election to win. The captain didn’t back down. “Mr. Vice President,” he said, “if you don’t come into the hospital tonight, there is not going to be an election.”

Nixon acquiesced, and began a 12-day stay in Walter Reed’s Eisenhower suite under the doctor’s care. Subsequently, Scalettar commenced a career-long study of Presidents and their health, and what their fitness can mean to elections and governing. His research continues today with the onset of the latest presidential election cycle involving two candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, whose physical and mental well-being have been questioned. Scalettar has explored the health histories of nearly every President, from Franklin Pierce (depression) to Franklin D. Roosevelt (polio and a stroke) to Biden, who had surgeries for two cerebral aneurysms in the 1980s.

Dr. Raymond Scalettar ’50

But on September 9, Nixon discharged himself against Scalettar’s wishes. “I was concerned he was still ill,” Scalettar says. “Had he been a private-practice patient, I would have signed him out ‘against medical advice.’” Three weeks later, in a televised debate with Kennedy, Nixon looked pale and frequently dabbed perspiration from his face. Election experts often cite his appearance next to the youthful Kennedy as one reason for his narrow election defeat. “His illness probably contributed a great deal to [his loss],” says Scalettar. “He was never able to really get up to speed.”

Scalettar does credit Nixon — known historically for his sometimes-devious behavior — with being up front with the public while under his care. “He never interfered with the dispatches that his press secretary and I wrote,” Scalettar says. And in 1984 he detailed Nixon’s treatment in an article, “Presidential Candidate Disability,” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In the article, Scalettar, who later become board chair of the AMA, also urged that “[t]he electorate should know as much as possible about the physical and emotional health of our presidential candidates … The acute illness of a candidate for the highest political office could result in an election of the healthier candidate by default.”

Forty years after its publication, though, Scalettar says candidates and elected officials are now “worse” at disclosing health issues than when Nixon was running for office. As an example he points to a lack of information the public received when Trump was hospitalized during his presidency for Covid-19. More recently, he cites the case of current secretary of defense Lloyd Austin, who failed to alert even Biden when he was hospitalized for cancer treatment.

Scalettar acknowledges that HIPAA regulations and the Goldwater Rule, which prohibits members of the American Psychiatric Association from evaluating anyone they have not personally examined, limit voters’ insight into a candidate’s physical or mental well-being. “A healthy candidate has no problem releasing [medical information]. A candidate who has some illnesses would be reluctant to do so,” says Scalettar, who was a member of the Van Am Society and president of the Pre-Medical Society while at the College. “We need honesty and transparency. Will it happen? ‘Devoutly to be wished,’ to quote Shakespeare.”

Nixon left no doubt as to what he thought of Scalettar once the 1960 election was over, and he had lost to Kennedy. He invited the doctor and his first wife, Nada BC’50, to a gathering at his home a few weeks after the election. “When we walked in, he hugged her and thanked her and told her, ‘You have one tough husband,’” Scalettar says with a smile. Then he adds, “I’ve often thought that had I missed the diagnosis, he never would have been President at a later time — and there never would have been Watergate. So, there was an historical aspect to it.”

Charles Butler ’85, JRN’99 is a journalism professor at the University of Oregon. He is researching a book on Lou Little.

More “Online Spotlights”

- 1 of 3

- ›