Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

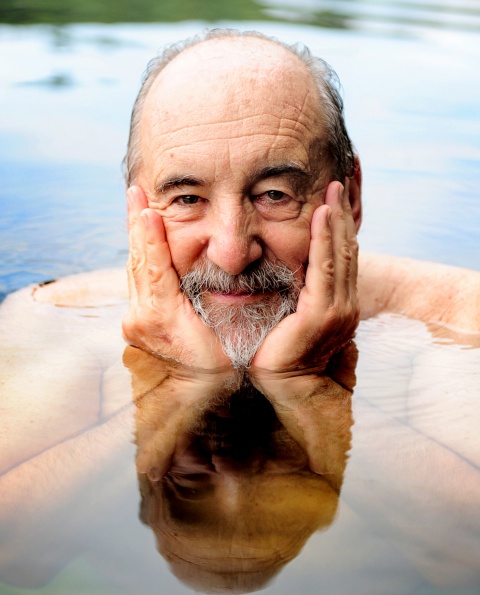

Take Five with Allen Young ’62, JRN’64

Young earned a master’s in Latin American studies from Stanford and a second master’s, from Columbia, in journalism. He was awarded a Fulbright to go to Brazil and spent three years in South America. Young left his career goals behind to devote himself wholeheartedly to a variety of causes: From the Post he went to Liberation News Service, and later edited pioneering gay liberation anthologies. Tired of dogma, he put down new roots in one of the most rural parts of Massachusetts. His last two jobs were with the Athol Daily News as reporter and assistant editor, and with the Athol Memorial Hospital as director of community relations. Young continues writing and hiking in retirement, and recently published his autobiography, Left, Gay & Green: A Writer’s Life.

What were you like when you arrived at Columbia?

Lined up with other freshmen in our mandatory blue beanies, waiting to register, I was overjoyed. I felt very fortunate to have received financial aid from Columbia and New York State, because my parents could not afford the expense. I was proud of my success as a high school student, and unaware of what it would be like to be among many other successful high school students. I also had a strong competitive aspect to my personality and I directed it immediately toward the idea of becoming the editor-in-chief of Spectator (which I did).

I arrived on campus, however, with significant inner turmoil around my sexuality. In high school, I had some homosexual experiences, and clearly my desire for more was powerful, but the overwhelming need to hide it was clear to me. This was an era when the words “gay” and “homosexual” were rarely heard and never seen in the media. The psychiatric establishment pronounced that we were mentally ill, and the government agreed. Our sex acts were serious crimes. I felt I needed to date girls, present myself as masculine as possible and try to avoid the shame and opprobrium of being gay. That was a heavy burden for a 17-year-old boy who also wanted to be a good student and become a campus leader. And yet I ended up having a wonderful experience.

What do you remember about your first-year living situation?

My roommates in Livingston Hall were John Modell ’62, GSAS’69 and Peter Berman GSAPP’69; both were affable and easy to live with. Early on, I asked Barnard student named Annabelle out on a date and when she turned me down, I decided that a “normal” boy would get drunk to drown his sorrows. I had never consumed alcohol but I knew there was a drink called Seven and Seven, so I bought some Seagram’s Seven whisky, 7 Up soda and pretzels, got drunk and threw up in our dorm room. Peter and John cleaned up and were very kind to me. I’ve heard that today’s college students want all kinds of amenities — one that we had was Irish cleaning ladies. I don’t remember ever complaining about any aspect of our dorm life.

What class do you most remember and why?

Professor James P. Shenton ’49, GSAS’54’s American history class was my favorite and most memorable one, and I’m certainly not alone in feeling that way. His lectures were always interesting, thought-provoking and exceptionally entertaining. Without thinking about it at the time, I am convinced he genuinely loved his students and knew he had a calling to be a teacher. When he died, I made a point of making a special trip from Massachusetts to New York City to attend his memorial in St. Paul’s Chapel, and I was moved by the experience of grieving along with many alumni.

Did you have a favorite spot on campus, and what did you like about it?

The Sundial was special because it was a regular place for the exercise of free speech and a gathering place for students who came from left-wing families. Students who wanted to speak out against the remnants of McCarthyism and the Cold War, racism in the South and especially, the testing of nuclear bombs, gathered there to form a kind of activist community. We also sang folk songs together — informal hootenannies that were so much fun.

What, if anything, about your College experience would you do over?

Instead of having a repressed affair with a handsome, brilliant roommate, as I did, I would ask him to marry me, and perhaps he’d say “yes.” But that’s like Christopher Columbus saying if he could do it over, he’d take a jet plane across the Atlantic.

More “Take Five”

- 1 of 32

- ›