|

|

|

|

|

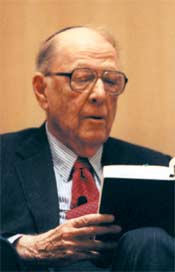

ALUMNI PROFILE

He entered the College at 16 and graduated at 20 after serving

as a staff writer of the Spectator and editor of the Jester, a

portent of literary things to come. Herman Wouk ’34

went on to become one of this nation’s greatest storytellers,

and he recently returned to Morningside Heights to commemorate the

50th anniversary of the publication of his Pulitzer Prize-winning

novel, The Caine Mutiny. Wouk’s reading on February 7 at the Kraft Family Center

for Jewish Student Life had been postponed from last fall following

the events of September 11. The event was held in conjunction with

the Rare Books and Manuscript Library, where many of Wouk’s

papers are housed. Wouk briefly addressed the audience of several hundred,

reflecting on what he described as the unexpected success of his

novels, which include Winds of War and War and Remembrance.

He also reflected on his days at the College, which awarded him the

Alexander Hamilton Medal for distinguished service and

accomplishment in 1980. “Columbia is, in effect, a

philosopher’s holiday,” Wouk said at the time,

referring to the title of a book by one of his favorite professors,

Irwin Edman ’16. “Philosopher, because you came to

grips with ideas and values that matter most. Holiday, because it

is exciting and alive and great fun. It’s a glorious school.

I owe what skill I have in the wielding of the English language to

what I learned at Columbia.” The son of Russian Jewish parents who emigrated from Minsk, Wouk

grew up in the Bronx, attended public schools and enrolled at

Columbia at a time “when great numbers of Americans, young

and old, came to believe that the capitalist system had betrayed

the citizenry, and that the whole structure was obsolete and

doomed. We had a spell of upheaval and agitation at Morningside; it

took place in the spring, as those things do. Thirty-five years had

to pass before an equally radical crisis in American life, the

Vietnam War, would evoke in Columbia College a comparable

springtime storm. “Trustees are embarrassed at such tempestuous moments, and

alumni fret. As my hair has gone from thin and black to thin and

gray, I have evolved from a vocal demonstrator to an anxious

fretter. But now, as then, I am secretly proud of what these rough

moments indicate. My school dwells at the leading edge of social

events and of progressive thought. Its situation in New York, the

world’s greatest city, so wealthy, dazzling and racked by

change, guarantees this. In the long, quiet years, as well as in

the brief troubled outbursts, Columbia is — to use the vivid

jargon of the moment — where it’s at.” In introducing Wouk, who will be 87 on May 27, Dean Austin

Quigley called him a writer who “has displayed a variety of

talents — an indispensable gift as a storyteller, a capacity

to create vivid and original characters, a remarkable ability to

depict in evocative detail social and historical situations, a

highly developed sense of humor and irony, and in the midst of it

all, a strong sense of moral imperative, of the importance of

understanding how human beings make choices, how people invoke,

abandon and defend values. This is not the moral imperative of an

ideologue who thinks he knows what is best for everyone in all

circumstances, but the moral imperative of someone who recognizes

with sympathy and humor the force of the old phrase that if we do

not all hang together, we will surely hang

separately.” Quigley concluded his introduction by describing Wouk as “a true son of Columbia, a man of great religious faith, great artistic talent, and great human achievement.”

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||