We pay tribute to the campus centerpiece, completed in 1897.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

We pay tribute to the campus centerpiece, completed in 1897.

Low Memorial Library, the first major building to be erected on the Morningside Heights campus, is having a big birthday this year. To celebrate, we raided the Columbia University Archives, requested insights from alumni architects and historians, and recalled memories from years of Steps fans. We love you, Low!

— Jill C. Shomer

Low Memorial Library, circa 1897.

Courtesy Columbia University Archives

An 1897 pamphlet summarizes Columbia’s lofty aims: “[It] is not so much a storehouse for books as it is a laboratory for those who are to use books. Quite as much thought has been given to the reader as well as the book.”

The Rotunda was conceived as the principal reading room, modeled after the main reading room of London’s British Museum. The architects designed a circle of tiered desks fitted with bronze reading lamps and bookcases that held 12,000 volumes. Stacks on the floors beneath the reading room housed an additional 150,000 volumes, while another 16,000 were shelved in the galleries above. At full capacity the library was expected to accommodate 1.9 million books.

Low would also be home to campus administrators: Seth Low held public office hours in the President’s Room — Room 213 — but worked in Room 307. (In 1948, Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first University president to occupy the current suite of offices on the second floor.) The Trustees, meanwhile, have always convened in Room 212.

The building was renamed the “Seth Low Memorial Library” by President Nicholas Murray Butler CC 1882 in 1935, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987.

McKim recommended sculptor Daniel Chester French for the commission (the artist was well known at the time, and would go on to design the Pulitzer Prize and the statue of Abraham Lincoln inside the Lincoln Memorial, among other monuments). French aimed to create “a figure that should be gracious in the impression that it should make, with an attitude of welcome to the youths who should choose Columbia as their college.” Early drafts featured Alma with her hands in her lap; after a round of critique, French changed her arms to be outstretched and holding a scepter. His final design was approved by the Trustees on March 4, 1901; the total cost was $20,000.

Alma Mater was installed in 1903. McKim was said to be delighted; he described Alma as “dignified, classic and stately ... exhibiting as much perception of the spirit and freedom of the Greek as any modern can.”

The dome under construction in June 1897.

COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Nott Memorial library reading room, 1936.

COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, SCHAFFER LIBRARY, UNION COLLEGE

Enter Dixon Ryan Fox CC 1911, GSAS 1917, a well-liked American history professor at the College. It was thought he would succeed Butler as University president, but in 1934, with Butler seemingly having no plans to retire, Fox left Columbia to become president of Union College in Schenectady. He returned to campus in 1935 to receive an honorary degree at Commencement; while visiting the Low ceremonial space, Fox found the old reading room furniture.

Union College happened to have its own iconic round building, Nott Memorial, and Fox asked Butler if he could have the McKim, Mead & White pieces for its library. With the Trustees’s consent, they were loaned to Union; the Low Rotunda furniture remained in Nott until the library was relocated in 1963.

Even before we started gathering responses for our 2021 online feature “Your Favorite Campus Places,” we knew the Steps would be number 1. And it was, by a landslide — they’re just that special to you. Here are a few of the memories we’ve heard through the years:

I always look to sitting on the Low Steps as a quintessential example of carefree youth and fun.

— Dr. Diane Hilal-Campo ’87

I know it’s cliché, but there was nothing like experiencing the Riot of Spring on the Low Steps. Glorious.

— Lawrence Trilling ’88

Every spring, after a long cold winter, all these pale, eager students would venture out of hibernation, gathering on the Steps in T-shirts, shorts and sundresses, and hang out together until the sun went down. It felt like the ideal college experience.

— Germaine Choe ’95

It was the jumping-off point for so many idyllic afternoons. It became increasingly difficult in the spring to go to your classes on that side of campus because every time you passed by, groups of friends would shout at you to come hang out.

— Cassius Michael Kim ’02

Low Steps is the best place on campus to hang out, people watch, eat, talk, read and just be.

— La Toya Tavernier ’05

Low on the Silver Screen

The building has played a role in these films:

Simon (1980)

Ghostbusters (1984)

Spider-Man (2002)

Spider-Man 2 (2004)

Spider-Man 3 (2007)

Hitch (2005)

The Nanny Diaries (2007)

The Post (2017; acting as the U.S. Supreme Court)

There is a masterly sequence of spaces in the design of Low Library that starts on 116th Street and ends under the dome. It was meant to lead students and scholars from the New York City street, up a series of stairs funneling us progressively into the orbit of Low Library, a cosmic universe of knowledge where we would be conducted through a vestibule — stepping on the way over the signs of the zodiac — to the central desk of the reading room to request books from a desk that was both the center of the campus and in the axis of the heavenly spheres above on the inside surface of the dome.

— Barry Bergdoll ’77, GSAS’86

Interim Department of Art History & Archaeology chair (2021–22), and the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History

When I first saw Low Library, I found it impressive yet unsettling. After attending high school in France, I found the Morningside Heights campus full of American bravado — overscaled — so unfamiliar to my refined continental eye.

The campus is inherently American: Charles McKim’s urban ode to Thomas Jefferson’s bucolic University of Virginia. The library, at the center point of the campus, is conceived on a brash 19th-century scale. The soft pink brick of Jefferson’s rotunda is reinterpreted in Low’s massive Indiana limestone walls, fluted ionic colonnade and dome that rivals the Pantheon’s. And then there are the anthemion, Vitruvian scrolls, dentils, bead and reel, egg and dart — the goodies of Classical architecture. The building boldly and unapologetically proclaims the importance of knowledge as a higher purpose.

I quickly got over my French reticence.

The recent interior restoration shows us McKim’s colorful intention — as though a gem-filled geode has been cracked open. The rich entrance vestibule showcases a marble bust of Pallas Athena, a marble floor beneath the intricate coffered plaster ceiling, supported by gilded-topped Connemara marble columns. Beyond is the voluminous former Reading Room. High above, four giant arched thermal windows send shafts of sunlight angling in. For those missing the sadly destroyed Pennsylvania Station, here is a hint of what that building was like.

Low is a fitting stage for luminaries (like Jacques Cousteau, whom I memorably heard speak there in 1978), modern thinkers in the tradition of Plato and his marble colleagues looking down from their perches on the parapet above.

— Tom Kligerman ’79

Architect, author and partner, Ike Kligerman Barkley

I have long admired Low Library as an architectural masterpiece, not only for the building itself, but also for how it embraces its site. Low seamlessly integrates Columbia’s upper and lower campus into one uniform plan, forming the heart of the University. Its inviting main steps, so beloved by generations of students, cascade toward College Walk like a stone waterfall. It is Classical city planning at its best (no surprise to students of the Core Curriculum).

I wonder, however, how many Columbia students have ever set foot inside Low’s interior, other than for a sneak peek? Now that the Business School is moving uptown, maybe some of Low’s offices could relocate to Uris, thereby allowing Low to provide more student-friendly spaces for classrooms, club offices, practice rooms and student publications. Just a thought — but I think McKim would approve.

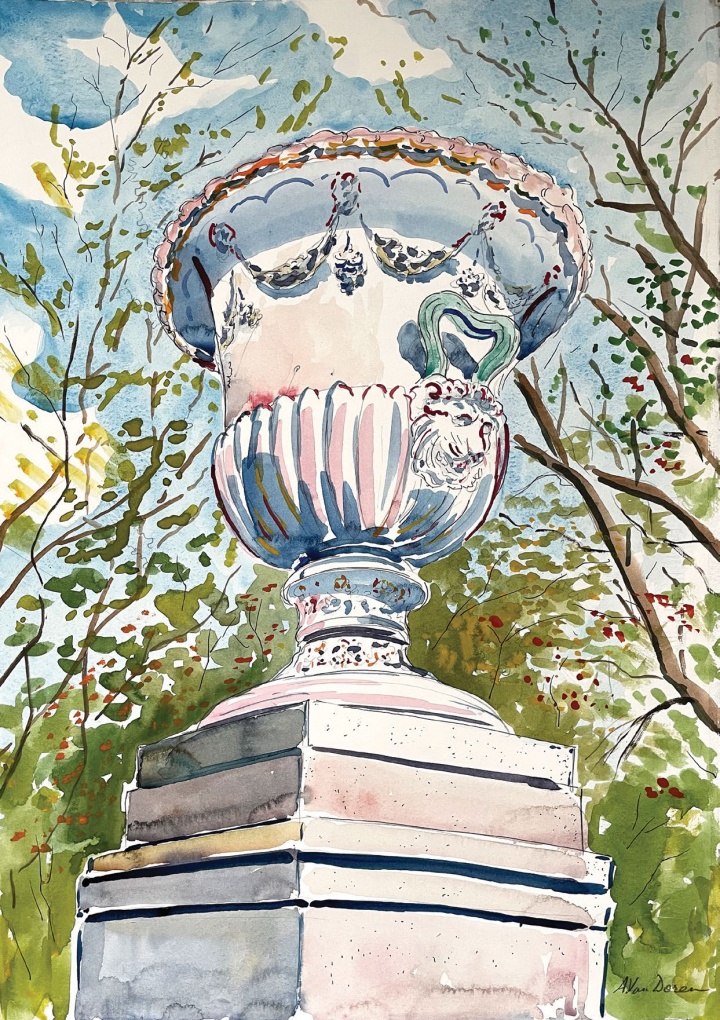

— Adam Van Doren ’84, GSAPP’89

Author, artist and filmmaker

To me, the most significant feature of Low Library is the way the building generously creates a backdrop for the most amazing public space at the heart of the campus. Perhaps it is the rising elevation from the plaza to the top of the Steps, which seems to place the activities and lives of Columbians on a pedestal for all to see. As a student, I had only been in the actual building a handful of times, but there was not a day that went by when I did not walk, sit, eat or drink on the Steps a few times.

— Jenny Wu ’97

Architect, designer and partner, Olyer Wu Collaborative

The best definition of a university is, to my mind, a city from which the universe can be surveyed.

Aesthetically ancient but technologically advanced, Low Library rose to this challenge. Its walls are several feet thick, thicker than was necessary in an 1890s America that had moved on from heavy stone construction to steel-frame skeletal structures for skyscrapers and railroad stations. Buried within hundreds of tons of Milford granite, Indiana limestone and the architecture of antiquity were the latest technologies: electricity, steam heating, Corliss steam engines and internal plumbing at a time when hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers still used outhouses.

The great library aimed to collapse the universe into the size of a room. From the dome’s center was suspended a seven-foot-diameter white ball, which Scientific American described in 1898 as “Columbia’s artificial moon.” So that students could read by moonlight under a canopy of stars, the 500-pound ball was illuminated by spotlights hidden in upstairs galleries, reflecting the “moon” against the painted dark dome to resemble the night sky. (With no other point of reference except candles, Scientific American calculated the glow of Columbia’s moon as equivalent in power to 3,972 candles.)

But light technology had yet to be perfected, and the lightbulbs’ carbon filaments could only burn for two and a half hours before the moon went dark. As a result, Columbia needed to replace the filaments daily and could only illuminate the universe from 5:00 to 7:00 p.m.

The moon came down to Earth in January 1965. As part of an extensive renovation, a new light and sound system was installed in Low and the lunar cycles were left to the real heavens above.

— Myles Zhang ’19

Ph.D. candidate in architectural history, University of Michigan

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu