Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Student Fiction Contest Honorable Mentions

We hope you enjoyed “Host,” the winner of CCT’s inaugural student short fiction contest by Sophia Cornell ’20. Here are the two stories chosen as Honorable Mentions, from Philip Kim ’20 and by Rachel Page ’20.

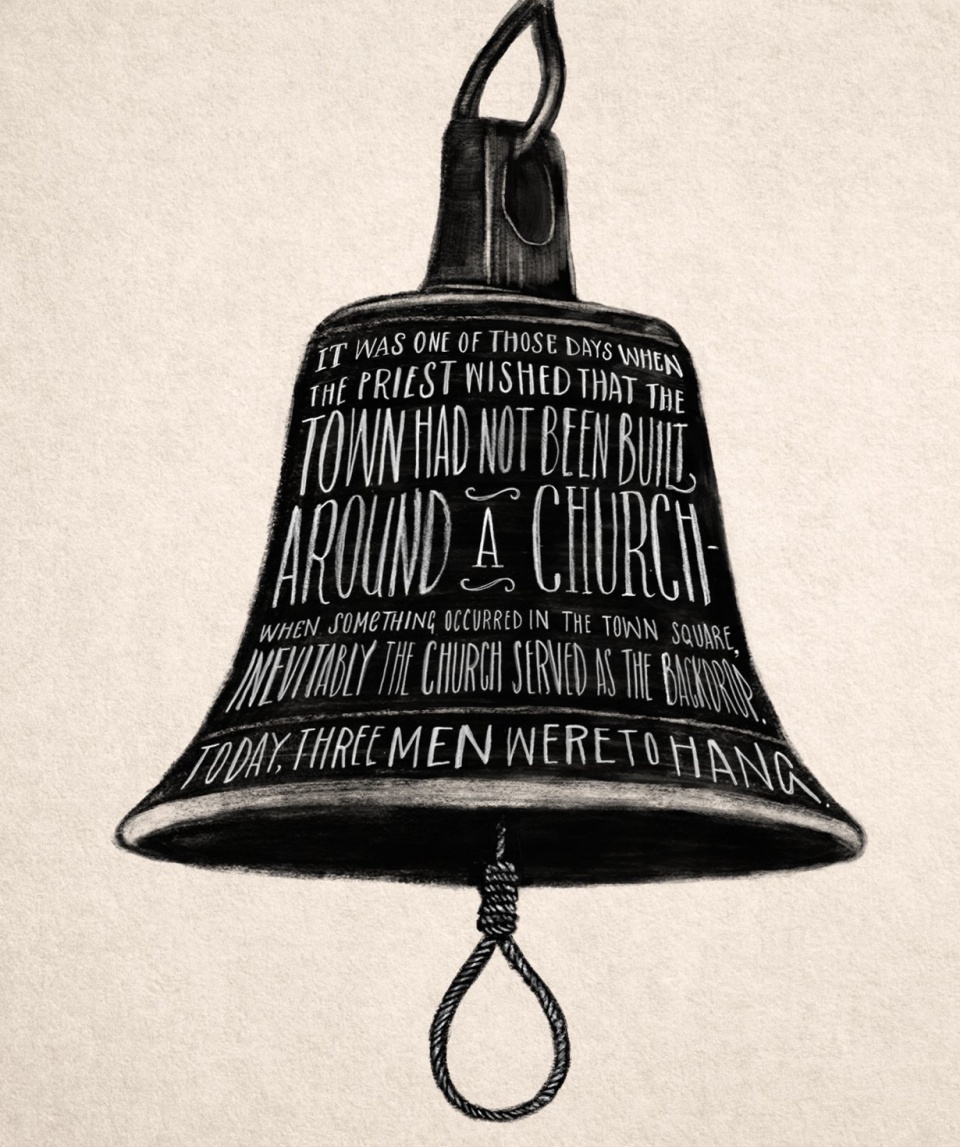

“Until the Bell Tolls,” by Philip Kim ’20

Illustration by Peter Strain

It was one of those days when the Priest wished that the town had not been built around a church — when something occurred in the town square, inevitably the church served as the backdrop. Today, three men were to hang.

The construction of the platform was done as quick as the trial. One wooden beam upon which the nooses were tied; one confiscated floor plank that could be kicked away; a pair of supporting triangular structures made up of three vertical beams, their ends converging at the end of the noose-tied strut. The platform was a pure sanded yellow, and it even still had a sawmill smell.

The Priest stood on the steps of the church, right behind the hanging platform. There were at least two dozen armed paramilitary men surrounding him. They wore Italian army-issue uniforms, black turtleneck sweaters and black field caps with metal skull insignias. While some of them set up a perimeter around the platform, others fanned out from the square and returned with parties of the uninformed and the no-shows.

These armed men were a new invention of the fascist government in Salo — what locals whispered and hissed were “Brigate Nere,” or Black Brigades. In the service of their disgraced dictator, Benito Mussolini, they enacted reprisals on the Italian populace for every partisan attack. The Priest had heard of executions occurring around Genoa further south, where the Black Brigades shot or hanged the relatives of known partisans, extinguishing seven families in the span of an afternoon.

There were suddenly shouts from within the crowd. The Priest saw an elderly couple, the Vallis, making their way to the front. Terence Valli, who once brought loaves of bread to the Priest in the expectation that he could make them multiply, didn’t waver in front of his wailing parents and stood tall next to his fellow partisans. Marie Fontana shouted encouraging words to her husband, Dominic, with a resounding voice she never once used until now. He was as serene before the noose as he was in church, head bowed forward. The entire family of the Serlios cried out to their beloved Ernesto, and he responded, with his emotion overpowering theirs.

In the crowd, there were many who were good friends of the Vallis, Fontanas and Serlios. Their voices soon joined those of the partisans’ relatives. The crowd collectively advanced a step, but a black uniform stopped them with a gunshot in the air. The captain of the Black Brigades barked the order to present arms, and in unison, the men separating the crowd from the hanging platform raised their rifles and bayonets. At this display, the citizens backed down.

Satisfied with the show of terror, the captain shouted to his men by the platform, “Tie the nooses! And put them ahead of the ear. Let them choke.”

The execution went ahead without delay. The captain kicked the plank away from the feet of the condemned. The nooses tightened, and the men began to choke. They floundered in the air. Their loved ones howled in that ineffable yet universal language of agony.

The Priest averted his eyes from the hanging men and spotted a familiar man in the furthest ranks of the crowd. His face turned away, this man was the only one who wept to himself. He clamped his hand over his mouth, as though something threatened to burst from his throat.

The Priest knew him to be one of his oldest parishioners. He brought his wife and children to the church on Sundays, but started coming by himself on Saturdays a month back. He would always come before sunset, right after finishing his day at the auto factory a few miles south in Piacenza and right before going home. He came to the Priest with a confession each time, at first seeking forgiveness for accepting payment from the Black Brigades in exchange for information on the activities of the partisans in the mountains. Then, a week before the hangings, the man admitted he had given up people of his own community.

The Priest glared at the informant. I was able to tolerate his collaboration, if only because a clergyman has no place in this war. But … now he’s killed three of my parishioners … Lord, how can I say he is forgiven and turn a blind eye to those deaths? It’s against my responsibilities, but I need to do something about him lest more of my flock die.

But the Priest would think about the informant later. At the moment, there were families that sought solace in God. The Priest climbed back up the stairs into the church to receive them.

In the following days, the Priest received a grieving town in his church. But between services, he asked the families of the dead men for whatever information they had on the activities of their dearly departed. Of those families, the Serlios told him of one more partisan planted inside the town — a woman named Matilde. The Priest learned that the Serlios grieved in their own way, seeking vengeance rather than comfort, and they offered to deliver a message to Matilde for the Priest.

Writing the letter took nearly three days, as the Priest struggled to write down the informant’s confession. If not for the vivid memory of the hangings, he would have never finished it. This partisan, the Priest believed, would listen to him and help him deal with the informant.

A week passed. A muted feeling came over the town. There were fewer conversations had in the street. Heads were bowed as if the whole town was held to a vow of silence. The walls of the closely packed stone buildings, painted in yellows and pinks, no longer stood out. The shrubs and trees, when the sunlight fell on them, didn’t quite shine as brilliantly as before. Where he had once been overwhelmed by the aroma of freshly baked bread at the market stands, he smelled more cigar smoke and alcohol.

In the town square, the hanging platform had been left for future use. The nooses swung slowly in the wind.

Inside the church, at least, the world had not lost one bit of its color. Here the smell of the incense and candle smoke made the air thick and still. The high, vaulted ceiling made noises reverberate, so that the echoes sounded rich and deep. The aisles were lit up during the day by rays filtering through the stained glass windows. The benches had a wood grain surface that still gleamed despite how worn they have become, and the cold marble in the floors and structural supports had a timeless luster.

The Priest easily regained his composure once he was inside.

Before sunset that day, the informant came. He appeared in the narthex, with the town’s dulled color palette behind him. He came across as sheepish to the Priest, as one who thinks too modestly of themselves might when entering a holy place.

The Priest waited until he was within arm’s length of the informant before he spoke. “Good day. Have you and your family been well this week?”

“Father,” the man breathed with a deep voice at odds with his appearance, “We’ve been a little shaken this week … just as much as the rest of the town. Well, those who didn’t lose someone last week, anyway.” He fell silent and rubbed his shoulder.

“I’ve noticed it’s been quieter in town since that day,” the Priest whispered. “I hope Dona and the children aren’t taking this too badly.”

The informant blinked rapidly. “We’ve tried pretending like it never happened. Dona’s scared beyond belief, but she’s been hiding that for Aldo and Clara. I’m sure they’re old enough already to understand, but they play along too. It’s so hard on them, though. On me as well.”

He stepped close and whispered, “I wanted to believe they wouldn’t do anything more than imprison them, maybe rough them up for information. And yet, I knew they would hang partisans. It’s strange. I just — Father, I just never know best.”

The Priest donned a matching sorrowful smile, even as he was cursing his loyal parishioner in the name of Terence Valli, Dominic Fontana and Ernesto Serlio.

He put a hand on the informant’s shoulder and made him face the confessional further inside. “If you have something you wish to confess … ”

The informant nodded and walked ahead. “Thank you, Father. I only make it through these times because of your help.”

“You wait in there for me. I have some matters to attend to first.”

Only after the informant was behind the curtain did the Priest drop his smile. He turned to his pulpit and picked up an unmarked letter — Matilde’s reply.

She had agreed to take care of the informant. Discreetly. But there was a condition — with the government’s strong presence in Piacenza, the deed had to be done here in this church by next week. The Priest looked back at the confessional, and the bell began to toll.

The week passed quickly. It was apparent that the fighting in the surrounding areas had intensified when columns of fascist soldiers and fighting vehicles began passing through town toward the mountains. The Black Brigades conducted regular patrols on the streets. The town remained muted.

Right before sunset, the informant appeared. The Priest couldn’t stop looking back to the Bible in his hands. He had been on the same page of Proverbs for an hour now.

This week, the informant had a longer, more confident gait. He also held a parcel between his hands and an easy smile on his face.

The Priest briefly furrowed his eyebrows, wondering how a man with a guilty conscience could smile like that.

“Father, good day.”

“Good day.”

The informant tapped the parcel. “I wanted to thank you for listening to me this past month. So I bought this for you.”

The Priest nodded, accepting the gift with stiff hands. He hefted the parcel as he spoke, “Prosciutto? Prosciutto di Parma?”

The informant was beaming.

“I never realized you were so cultured when it came to delicacies.” The Priest rested the parcel on a bench. “You’re too kind.”

Probably bought this gift using money from the Black Brigades.

The informant’s face began to sink, eyes falling to the ground. “And I know I’ve asked a lot of you, Father … but will you please … ?”

The Priest wanted to turn him away. He closed his eyes and nodded, “Will you give me a moment to myself and wait in the confessional?”

“Of course, Father.”

“Thank you.”

The informant walked to the confessional, footsteps ringing out in the church. Once the man was behind the veiled portal, a new pair of footsteps sounded from the opposite direction.

The Priest turned around to see a short woman fast approaching. She wore a sanded yellow dress one size too big and a brown beret, which allowed only a few strands of black hair to slip out from underneath. Her complexion was bright, but her expression had no warmth. Behind her, three other visitors walked up the aisle and began ushering churchgoers outside.

Matilde spoke up, “That’s the man who got my men killed?”

The Priest looked back at the confessional. The Priest asked, his voice shaking, “Will it be quick?”

“No,” she said.

“Will it be painless?”

“It’ll be very painful.” With that said, she produced a steel wire garrote from the inside of her dress. The sight of the wire sent a chill through his soul.

The Priest sighed and felt a knot forming in his stomach.

“Go, Father,” Matilde ordered. “Give him his last rites. I’ll wait by the curtain until the bell tolls.”

The Priest hesitated at first but forced himself to march to the confessional. Each step took a conscious effort. All the while, Matilde stayed behind him and matched her steps to his. It was his longest procession.

“Father,” the informant said as the Priest entered the confessional. A translucent screen separated them, and pale orange light entered the space through a pair of windows. The panes were too cloudy to see through. There would be no witnesses.

The Priest stiffly assumed the position, with his left shoulder facing the screen and his head held high and facing forward.

The informant leaned forward in his seat and began making the cross. “Bless me Father, for I have sinned … ”

The Priest swallowed. “Pl — The bell will toll soon. Will you please wait until they’re silent?”

The informant answered, “Of course, Father.”

The Priest waited, taking quick and shallow breaths.

When the bell finally tolled, the Priest jolted in his seat. Whether the informant saw the movement or not, he never had the chance to say anything. Matilde phased through the curtain and had the wire around his neck before he could react.

The Priest shut his eyes and tensed up as he heard the informant start to choke, kick and throw his arms.

The bell tolled.

He was still sputtering despite the stranglehold she had on him. It sounded as though he were retching his lungs out. In pauses between the clamor and the horrible guttural noises, the Priest could hear the man’s attempts at syllables: “F … Fa … He …”

The bell tolled.

The Priest ground his teeth together. Perhaps it would drown out the cacophony across the screen. His teeth grew numb.

The bell tolled.

Matilde ordered, “Father! Come here and — ”

The bell tolled.

“ — restrain him!”

The Priest found himself moving right on prompt. He parted the curtain on the other side of the confessional and slipped into the narrow space. Matilde was struggling to starve the breath out of the informant, since he kept fighting back with his arms.

The Priest gripped both the informant’s arms and pulled them down.

The bell tolled.

The informant struggled with even more vigor, one last burst of adrenaline inside him.

The bell tolled.

The Priest tried to tie him down by wrapping his own arms around his body and hugging him close. The informant’s limbs began to slow down and lose their fight.

The bell tolled.

He gasped one last time before the air passageway in his throat was completely blocked. In his position, the Priest could feel the heartbeat slowing down until it faded away.

The informant fell limp.

The Priest removed himself only after the bell’s final ring had dissipated. He leaned his back on the confessional screen and let his head drop to his shoulder. Matilde put a finger against the informant’s neck. She looked at the Priest with an expressionless face and nodded.

He was dead.

The Priest closed his eyes and let his head bow forward. When he opened them again as Matilde’s men removed the body, he saw that the orange light had lost its shine. Everything inside the church looked muted to him.

“Rats,” by Rachel Page ’20

Illustration by Peter Strain

We call each other at the exact same time the day the towers fall. They say twins have special receptors in their brains that allow them to communicate telepathically; I don’t know if this is true, but I have the feeling that knowing each other for a lifetime means something in us is synchronized. I am visiting our father in the hospital and Georgia is across the city in our favorite coffee shop eating a bagel. Both of us saw it on TV screens. When we pick up we just sit there for a bit on our separate ends and breathe into the phones and this feels like enough. Georgia’s breath sounds like crumpling paper, like something being balled up into itself.

Our father turns over in his hospital bed, squints at the TV. “Is that the Empire State Building?” he says. The newscaster is crying; she keeps tapping the pressing at the little receiver in her ear like she hopes it’ll fall away inside of her. The camera zooms into the smoke that spirals out of the building until all we can see is black. Is that the Empire State Building? It could be any building; now it is nothing at all. I open my mouth to tell him but his eyes are already closed again, and I am glad because I do not want to be the bearer of any information right now.

“Yeah,” Georgia says, “maybe.” I imagine her eyes watching the screen just like my eyes are watching the screen. Both of us keep breathing. In the weeks to come, when the only question people ask is where we were on that day, we will say that we were with each other.

When we were kids our father kept rats in the house. The lab kind, all of them white and beady-eyed. He was a scientist and the rats were his pet experiment, the test subjects of a study he was doing on fear and its effect across generations. This, of course, being something we only learned years later, when we were old enough to understand words like “neuroanatomy” and “epigenetic” and “genome.” Back then they mostly just felt like pets. He’d let us feed them and sometimes even let them out of the cage onto his office floor, where they’d scurry about like blind things bumping into desk drawers and trying to burrow underneath the carpet. We gave each of them names after our favorite storybook characters: Madeline, George, Harold, Chrysanthemum. Maybe it was strange for us to love them so much, some transgression of the boundary between tester and subject. But he never let us watch when he was performing his experiments. Our only hint was the cloying smell of acetophenone that stuck to his office. Even now I cannot think about our rats without remembering that chemical scent, like melted cherry popsicles.

Our father published his first paper on the rats when we were in middle school. In it, he described his experimental procedure in detail: The rats were given shocks that were timed with the release of acetophenone, a gas he chose for its distinctive scent. He delivered the shocks in intervals of three. They were strong enough to be painful, he wrote, even in some cases to stun, but not to kill. The rats were allowed 15 minutes to recover and then the shocks would begin again. He did this seven times a day for five years. When the rats gave birth and he exposed their offspring to acetophenone, they showed a fear response even without the shocks. Conclusion: Fear can be inherited across generations. The journals loved it.

In the paper, and in the notebooks we’d find later piled up in his dusty office, there was no mention of our storybook-inspired names. Instead he’d assigned each rat a letter, A through K: A particularly thirsty today. D scratching at scab 2mm from tip of tail — try ivermectin? On these pages, in his scrawled scientist’s handwriting, our old family pets were unrecognizable. It was odd to think that this was how he had seen our rats, these animals we had grown up alongside. That after all of his years of feeding, of scraping cages and refilling water bottles, of tagging and tracking and careful observation, they had never become more to him than a series of letters on a page, alphabetically aligned.

Our father dies 10 days after the towers fall. We walk around the city together breathing in the dust of dead people, not wanting to let go of each other’s hands. When the little man on the crosswalk sign turns white and one of us starts to walk before the other it feels like a betrayal. Like if we were separated now it could be the last time. We go to our childhood home to collect his things, flip through the bookshelves of notebooks he organized by date and research subject. There are more of them than can fit in our arms.

In the months that follow we make the rounds to friends and family. Everyone is clinging to everyone else. Everyone has condolences to offer. We fly to D.C. to stay at the apartment of our childhood neighbor Billy Grayson, now a dentist in Takoma Park. He cooks dinner the night we get there; there’s steak that neither of us eats and mashed potatoes that we spoon mountainfuls of onto our plates. He tells us that there is a sniper in D.C. now who’s been killing people from afar. His daughter’s kindergarten class isn’t allowed to go outside for recess anymore. He’s started leaving work early so he can drive her home from school. “I don’t know how I’m supposed to raise her in this world,” he says. “There’s so much fear. Is this what she’s going to grow up knowing?”

Our father must have thought of this, of the possibilities of living in a world like this one. It was all there in his notes. The mechanisms of fear. He’d recorded the squeals of the rats as he shocked them, furry white bodies stumbling dizzy through acetophenone. He compared pitch and decibel levels in neat charts, each number resting square on top of another. Pulse rates and heartbeats that zigzagged across the gridded paper like uneven scars, the records of a feeling too terrible to be expressed in anything but data. Fear is something that can be inherited: What will this mean for the daughters of Billy’s daughter? Will they one day shy away from empty playgrounds, cling to their mother’s legs without knowing why?

After dinner Billy’s daughter takes us to her bedroom so we can help feed her pet snake. He eats dead mice; they come in a bag that looks like it could hold freezer aisle vegetables. She tells us they have to buy them frozen because pet snakes grow up in pet stores and never learn how to kill. If we put a live mouse in his cage it would fight back, scratch him. If it hit him in the right place he could even go blind. “Pretty scary for the mouse, too, huh,” Georgia adds. Billy’s daughter furrows her brows at her. “Are you leaving tomorrow?” she says.

“Yes,” I say, “we’re taking a plane. We’ll leave in the morning.”

Billy’s daughter takes one of the mice out of the bag by a stiff tail and drops it into the cage. “I took a plane once,” she says, “to Florida to see the dolphins. It was so big there was even a basement.” The snake is hiding behind a plastic rock; he darts his head out when the mouse drops, then pulls it back in again. We see the flicker of a pink tongue. Billy’s daughter nods wisely, tells us: “That kind of plane could kill a lot of people.”

In the security line at Reagan they pull aside a man with a turban for an extended search. We’ve never seen the lines this long. “I’m going to miss my flight to O’Hare,” the man is saying. “Please, it’s my son’s birthday.” We wonder to each other if this is true or if he’s only saying it to remind the guards that he, too, is a father. They corral the rest of us into smaller lines, asking us to please shuffle closer together. Everyone obeys. We inch forward between the dividing ropes, going nowhere. Someone in front of us asks if it’s true that they’re going to start taking fingerprints at every airport checkpoint.

When the plane lifts off we look out the window together for the sniper. It’s mostly a joke, but something in us makes it feel like it could almost be possible to see him straddling the Washington Monument. Or perched on top of Lincoln’s head, shooting at his image in the Reflecting Pool. But by the time we circle around the Mall we’re so high that any person would look like a smudge, assault rifle or no.

One day when we were kids we woke up and all the rats were dead. It was the end of our father’s experiment. When we went downstairs to tell him, he was at the kitchen table staring at the newspaper in front of him, but his eyes weren’t moving, and then we knew that he knew. He told us that it must have been something in the water, or maybe one of those bugs that the lady at the pet store was always warning us about. He knew it was a shock, he was sorry, these things just happen sometimes and we can’t explain why. He had made us both pancakes that he was keeping warm in the oven, but neither of us wanted to eat.

That afternoon we placed their bodies into tissue boxes lined with hay to be buried. Georgia cried; I wanted to but couldn’t. Our father watched from the doorway, unable even after the fact to breach his sacred role as experimenter. We had to ask Billy Grayson’s dad for a shovel so we could dig the hole under the forsythia bush in our backyard, a mass burial. Jumping on the flat top of the blade to break through the frozen earth, we crushed yellow flowers beneath our 12-year-old feet like stars.

Georgia and I used to wonder whether he had killed them. It was impossible not to; the timing was just too good. At the same time it was a possibility that neither of us truly believed, more like a joke we’d bring up whenever we were reminiscing about our childhood. We always envisioned the conversation he’d have with us years later, asking us into his office and telling us to sit before solemnly admitting to his crime. In this imagined fantasy we’d vacillate between reproach and forgiveness — “How dare you do this to us?” we’d say, indignant, refusing the comforting hand he offered in his apology. But in the end we would give in, enveloping him in the hug he used to call our “twinwich,” his body the filling between our two small slices of bread. He was our father, after all.

The university where our father taught holds a memorial for him. We go to listen to the keynote speaker, an old friend of his. He discusses the virtue of science in these troubled times and the importance of innovation, of the constant striving to learn new things about ourselves. It is a speech that could be made about anyone, and in this lack of intimacy it feels uniquely suited to our father.

After the speeches we stand by the table of soda and stale brownie squares and shake hands with all the people who pass by. “Such a brilliant man,” everyone keeps saying. “We were so lucky to know him.” We meet a grad student who was inspired to pursue his degree in experimental biology by one of our father’s lectures. Now he works in a physics lab crashing atoms into each other at the speed of light; he says this is the science of the future. One day we’ll be able to see the things that make up protons and neutrons, and then our whole universe will get smaller. He sips champagne throughout our conversation and asks for Georgia’s number at the end of it. She gives him mine; we like to play this game where we see how many dates it takes for them to catch the difference.

In the cab on the ride back to my apartment the woman on the mini TV screen talks about a war on fear. What we are supposed to do, she says, is to not be afraid. To have neighborhood potlucks. To fly flags. To submit joyfully to strip searches and to our bodies being examined through one-way mirrors. Like rats in glass cages, we cannot let them know that their shocks faze us. Georgia slips her fingers between mine. I have started locking my apartment door at night; I never used to do this.

We are at the point, still, where sometimes we have to call each other late at night with questions. Like: Did we really remember to bury our father, or was it all just a dream? Or: What do we tell our future daughters when they ask us where we were that morning? Do we talk about the TV screens, the burnt coffee, the crying? Are these things that you can be too young to know? Other nights we lie awake in our separate beds on separate streets thinking about the moment when the first grandchild rat smelled the acetophenone. For the first time his body does not feel like his own. There is no possible way for him to comprehend the source of his fear; it is etched into his genetic material, a scar he never earned. How does he run when there is nothing for him to run from? We imagine ourselves into his body, or him into ours, curved around our bedsheets like a fetus. Hiding from something we do not know how to name.

Our father must have reacted to this moment with joy. His hypothesis had been proven; the results were unprecedented. And what a rush, to see those thin whiskers quiver, to track the racing heartbeat. Maybe he grinned — maybe his heart rate, too, went up — maybe he took a break from his notes for a celebratory glass of champagne. I imagine him walking to our bedroom with this glass in one hand and his lab notebook in the other, the moment too fresh to let go of just yet. He needs to share this victory with someone. But Georgia and I are asleep, it’s past midnight and we’re children, and this — this is the image I am left with. My father standing in the doorway, watching us through the darkness, our two bodies leaning into each other like towers that have never learned to fall.