Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Artful Recollections of Great Books, Professors and Bars

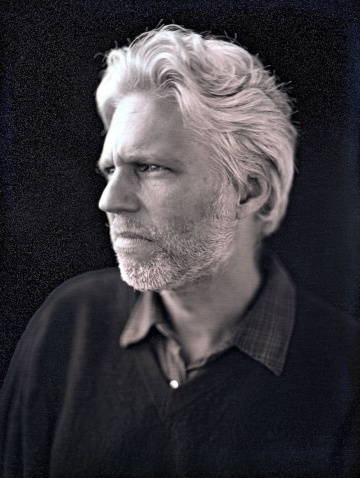

Daguerreotype by Jerry Spagnoli

What were you like when you arrived at Columbia?

I arrived as a transfer student from the University of Michigan. I was politicized by Ann Arbor, stung by rejection from Amherst, convinced I could write better than I actually could and absolutely on my own for the first time. But I knew two things: I desperately wanted to learn, and nourished by the myth of my mother’s post-college year in the city, I wanted to come to New York. I had experienced that desire the year before on my first trip to the city, with my mother. She went to a conference at the Journalism School, I went to the Guggenheim to see a Giacometti retrospective. Standing in that magnificent spiraling space, looking at those thin, anguished sculptures, I was as stunned as any astronaut setting foot on an unknown planet.

What do you remember about your first-year living situation?

“North of 72nd Street, there is no law, and north of 96th, there is no God,” said the cab driver who took me from the airport to my new home — not the cinderblock modernism of Carman Hall but the vast, decrepit prewar bulk of the Paris Hotel at 95th and West End. So, only the border of the wilderness. As a transfer student, there was no dormitory space; I learned first-hand about SRO hotels. Sex workers often trolled the lobby and the streets nearby, and I picked up my mail from the ancient Russians who managed the place. My tiny room was on an airshaft; I listened to saxophone practice and the fierce domestic strife of a couple up the shaft, who sometimes concluded by throwing their dishes out the window. But there was an upside: Because it was a hotel, I had fresh sheets and towels twice a week.

What Core class or experience do you most remember, and why?

Repeat the names — these are people who should not be forgotten (every graduate has such a list): Wallace Gray; Robert Egan; David Josephson ’63, GSAS’72; Jeff Kindley ’67, GSAS’71; the goat-bearded Carl Singer GSAS’70; Richard Steiger; and Gene Santomasso GSAS’73, of blessed memory — all except Gray were junior faculty; most joined the great diaspora of teaching talent out of Columbia. For the most part, I avoided the senior stars like Edward Said and George Stade GSAS’65, although their lectures were electric. Instead, I looked for people I could talk to, more like the teacher I like to think I am now. But my favorite Core class was Santomasso’s Art Humanities. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, it set me on the path I have now walked for nearly 30 years. I think of him almost every day. He said to us, “The Met just bought this portrait [of Juan De Pareja] for $5 million. Go see it and tell me if they paid too much.” (They didn’t, as he well knew.)

One other episode I can’t neglect because I think about it, too: Singer would begin his brilliant discussion of Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers, then suddenly stop with a supplicant gesture. From the back, one of the seniors would throw him a pack of cigarettes. He would recommence, only to stop a few minutes later. From the back would come sailing a packet of matches. He would light up, and we were off. The same ritual repeated every week. When he decided, during the protests of 1972, to move the class off-campus, the same senior group, including the most political students I ever met, refused to go, and entered into a heated discussion with him about the importance of what we were doing in the classroom. He treated them as colleagues, and they addressed him as a peer. I didn’t imagine being him, but I wanted to be them. In some way I still do, even though several of the students I have taught at SVA are now my colleagues.

Did you have a favorite spot on campus, and what did you like about it?

I spent an inordinate amount of time in Book Forum and in the miniscule Columbia Bookstore fantasizing about books to read and what the other classes were reading when I could have been actually reading the books. But rather than a favorite spot, it’s probably more appropriate to focus on a place where I always seemed to wind up, which was The Gold Rail, on Broadway. I would classify it as somewhere between the more storied and ambitious West End and a dive bar. But you could eat. So that’s where I went. It had a cast of local characters and an occasional visit from Moondog, that Black Viking poet from another planet. Most memorably, one of the habitues would routinely put the touch on students at the bar, as happened to me. I was dressed in fringed boots, a fringed jacket like Davy Crockett’s, a hand-embroidered shirt and sash from Santa Fe, shoulder length hair and a headband. My temporary friend asked me to buy him a round and I did. He took a pull, looked at me and said, “You’re all right. I kind of even like you. But you look ridiculous.”

What, if anything, about your College experience would you do over?

This question is usually answered by a litany of courses you neglected to take, wished you had taken or otherwise missed. Failed love affairs, moments of moral laziness and egotistical myopia can also be referenced. Not taking enough advantage of the city? I have a sackful of those regrets, starting with not spending enough time looking at art when Soho was just ramping up. Yet the one that stupidly gnaws at me was not having come close to achieving what I might have in the swimming pool.

I was captain of the 1973 team (Coach Don Galluzzi said, “I should tell you that the vote was not unanimous”). But it wasn’t the ancient facility (we paddled among Greek columns beneath the gym); a culture antithetical to sport (our backstroker was 6-foot-3 and weighed 116 pounds — he was trying to avoid the draft by self-starvation); or sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll that deterred me. It was Hegel. And William Blake. And Wittgenstein. And Borges. Practice was at 7:00 a.m. and it was 1:30 a.m. and I wanted to hear what my friends had to say about The Phenomenology of Mind. So I was not the unanimous choice by swimmers, but swimming could never be a unanimous choice for me.

More “Take Five”

- 1 of 32

- ›