Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

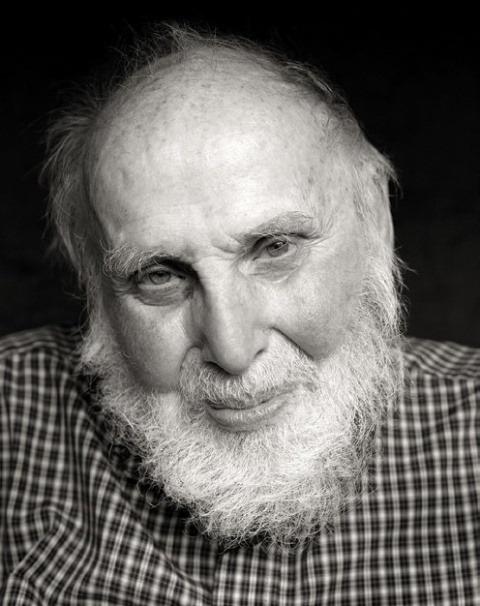

Arthur Ashkin ’47, Nobel Prize-Winning Physicist

Jörg Meyer

That was the challenge met by Arthur Ashkin ’47, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics on October 2, 2018, for his groundbreaking research in laser physics over the course of more than 50 years. Specifically, Ashkin was recognized for figuring out how to harness the power of light to trap and study microscopic objects. Ashkin’s invention of optical tweezers enabled scientists to grasp “particles, atoms, viruses and other living cells with their laser beam fingers,” creating ways to observe and control the machinery of life, wrote the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

On September 21, 2020, Ashkin died at his home in Rumson, N.J., where he had worked on various projects until his passing. He held 47 patents and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2013.

“I was interested in science since I was a kid,” Ashkin said when his Nobel Prize was announced. “So I tell my wife that’s the only thing that I’m really good at.”

Ashkin was born on September 2, 1922, in Brooklyn, N.Y., one of four children; his older brother, Julius ’40, GSAS’44, also became a physicist and played an important role in the Manhattan Project, the secret e ort during WWII to develop the atomic bomb. After graduating from James Madison H.S., Ashkin followed Julius to the College and worked in the Columbia Radiation Laboratory on magnetrons, which produced microwaves and were a precursor to the laser. He joined Bell Labs after obtaining a Ph.D. from Cornell in 1952 and worked there until his retirement in 1992. He led the lab’s laser science department 1963–87, and it was there that he developed his optical tweezers.

Ashkin, who had been interested in the subject of light pressure since childhood, created his optical tweezers by shining a laser through a tiny magnifying lens, which creates a focal point for the laser. Particles are drawn in and trapped there, unable to move. Trapping biological material proved to have groundbreaking practical applications in research and in understanding the behavior of the basic building blocks of life, like DNA. Today, optical tweezers are widely manufactured and sold to researchers.

Ashkin was awarded one-half of the 2018 physics prize, sharing it with Gérard Mourou of France and Donna Strickland of Canada. At 96, he was the oldest recipient of a Nobel Prize at the time; the next year, John B. Goodenough received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry at 97. Ashkin is survived by his wife, Aline, a former high school chemistry professor; sons, Daniel and Michael; daughter, Judith; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

— Alex Sachare ’71

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu