How the experience of the Core will evolve for today’s — and tomorrow’s — students.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

How the experience of the Core will evolve for today’s — and tomorrow’s — students.

Larry Jackson, associate dean of Academic Affairs, Core Curriculum and Undergraduate Programs.

Jörg Meyer

But even as the Core’s framework endures, it must evolve. How the curriculum could best respond to the moment was a vital question at the outset of this academic year, and its continued evolution will be an area of focus going forward. The Committee for the Second Century of the Core, made up of a diverse, multi-generational group of College leaders, alumni and students, was recently established; the group will convene regularly throughout the year to reflect on and reevaluate the Core’s purpose and the experience it offers to each student, particularly for students of color, who may face systemic injustices in their everyday experiences. The ongoing dialogue is an effort to improve the College’s articulation of the Core — helping students to better understand why they take it and how to approach it — and to determine how the curriculum can have the most meaningful impact on current and future Columbians.

Changes are already underway. Larry Jackson, the associate dean of Academic Affairs, Core Curriculum and Undergraduate Programs, spoke with Columbia College Today about the importance of the Core in difficult times, the collective effort he and Core faculty members have made to reframe the curriculum, and the goals of presenting a wider range of experiences and perspectives to the Core community.

Larry Jackson: When the Core was founded in 1919, the intention was to help students prepare to grapple with what the creators called “the insistent problems of the present.” At the time, this included the destructive fallout from WWI, sweeping political changes, a deadly flu pandemic, police and vigilante violence against African Americans, and an anti-immigrant sentiment that led to the arrest and deportation of thousands. The idea of the Core as a way of responding to the problems of the present is something that we continue to think is important; the curriculum has evolved over time in order to meet that original goal.

Jackson: One of the problems that we have today is we have lost the personal element that we once had in democratic life. As there’s been a shift to social media and cable news, it’s become a lot easier to vilify people who disagree with us. We don’t talk to them face to face; we deal with cartoon versions of them. So I think that one of the things we try to emphasize in the Core is that we’re creating a personal space in which people face to face can grapple with ideas that they disagree with, ideas that might even offend them deeply.

I think the other side of that is recognizing the limits of civil conversation and trying to foster the empathy and the perspective that will help students understand those limits and what might drive people to those limits. Yes, we want to encourage civil conversation, but we also want to take seriously instances where people feel that they are past that. Something has happened, they have experienced violation, they have experienced something that has made their entry into civil conversation impossible. We want to encourage the empathy, the imagination, the perspective that will allow us to understand what drove people to that point.

Jackson: I go back quite a bit to Hannah Arendt; I find a lot of comfort and perspective in her work. I first read On Revolution five or six times over the course of a year. It’s a strange work that combines history, politics and philosophy, and I just found it so amazing and inspiring. It was what made me want to study philosophy and get my Ph.D. I think Arendt’s study of totalitarianism — which is on the CC syllabus now — is really penetrating if you want to understand the dangers of totalitarianism in any time or place; she provides a lot of insight. Arendt really was one of the most original thinkers of the 20th century. She makes my heart flutter.

Jackson: We are grappling with the problems of Covid-19, and we’re seeing a nationwide reckoning with a long history of anti-Black racism — problems that are similar to what students were facing in 1919 — so we continue to look to the Core as a way to be responsive. In particular, we looked at the syllabi for all five courses and tried to build bridges between the works already on the syllabus and some of our present-day issues. We are also introducing new works that we think will be especially effective.

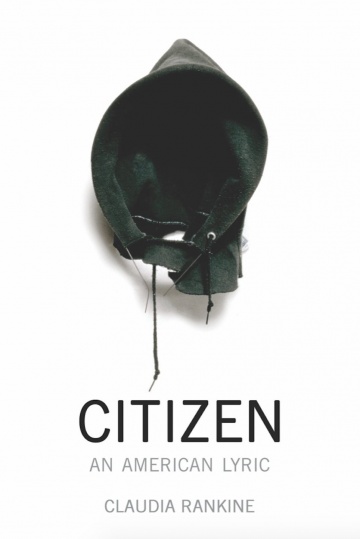

Jackson: I’m pleased to say that all five of the Core courses have added something. When Joanna Stalnaker, the chair of Literature Humanities, and I talked about what students should read during the summer, she suggested Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric — it just seemed like it was absolutely the exact right text for the moment. [See “Citizen Gets a Close Read,” below] The use of first- and second- person in Rankine’s text very compellingly addresses the experience of African Americans. It’s an extraordinary work.

For Contemporary Civilization, chair Emmanuelle Saada and I wanted to introduce a unit on race and justice; with the support of the CC faculty we added texts by David Walker, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., Angela Davis and James Baldwin.

In Music Humanities, there’s already a unit on jazz, but chair Elaine Sisman and her colleagues have extended that to look at the ways in which African-American jazz musicians have been responsive to the question of anti-Black racism. They’ve included Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and Charles Mingus’s Fables of Faubus, works that were composed specifically in response to the racism in the Black Freedom movement.

Art Humanities was already undergoing a major overhaul of the syllabus — the first since the course was created in 1947. Chair Noam Elcott ’00 and other faculty have introduced artists of color like Romare Bearden and Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as introducing race as a subject, looking at the ways that people of color were being depicted in art. That was already happening but now they’re trying to emphasize and elevate that a bit more in the teaching.

And finally, Frontiers of Science. Frontiers has four units that are constantly rotating and always include the most cutting-edge, relevant research. There were already faculty who were talking about the South Bronx having a higher rate of asthma than the rest of New York City, one of the highest in the country. So that was a good example for a conversation about environmental racism. Now they’re elevating those kinds of topics; for example, when they talk about the ethics of scientific studies, they’re going to look at the Tuskegee Experiment. They’re going to incorporate anti-Black racism into their discussion of science.

Jackson: I always love to point out that the first nine years the Core existed — when it was just one course, Contemporary Civilization, from 1919 to 1928 — there were seven different syllabi. It went through seven revisions in one decade. These kinds of changes have been ongoing throughout the Core. For a number of years now, Lit Hum and CC have undergone a review every three years. Some significant changes occurred after women were accepted to the College in the early 1980s: Jane Austen was added to the Lit Hum syllabus, then Virginia Woolf and Toni Morrison. In 1995, CC added the Quran, and Islamic philosophers were also added to the syllabus. The triennial review was not taking place in Art Hum — there have been some revisions since 1947, but this is the first major overhaul. Music Humanities is now also being revised every three years; that’s a fairly new development. And again, Frontiers of Science rotates its units every year to teach the most relevant research possible.

Those are the bigger changes, but within those frameworks there’s been flexibility for instructors to add texts and to make decisions on their own about what they’re including. The changes we’ve made this year are very much consistent with that, where we saw openings in the syllabi where we could introduce new texts. Lit Hum and CC will undergo their syllabi review this year, and we’ll see what comes out of that. The reviews will take place in the spring term, and the faculty chairs are already working to make the process as inclusive, coordinated and transparent as possible. There is also great interest in the perspectives that the Committee for the Second Century of the Core will provide.

Jackson: First and foremost, we want the Core community to be inclusive and diverse. It’s incredibly important that the Core present a range of experiences and identities — nobody should go into a Core classroom and feel like this is an experience they can’t have access to.

We can never represent all the diversity and richness of the human experience on a single syllabus, but we want to present as broad a range of experiences and perspectives as we can. We think that’s the best way for students to be able to find themselves in these works, it’s the best way for students to be able to grow and it’s the best way for students to prepare for the world they’re going to be going into when they graduate. We’re updating and adding to the Core partly because we want students to feel like they’re part of this community — we don’t want anyone to feel shut out, we don’t want anyone to feel like they don’t belong — but also because these are really important texts that are going to prepare students for an uncertain world.

Last summer, after protests decrying anti-Black police violence rose up in all 50 states, first-year Lit Hum students got a new reading assignment: Claudia Rankine SOA’93’s Citizen: An American Lyric.

Citizen, published in 2014, chronicles the experience of racial micro-aggressions in essay, image and poetry; Rankine’s use of second person, the narrative of you, is an especially powerful reckoning. “Citizen confronts the incessant lived reality of anti-Black violence from a perspective that is both intimate and collective,” says Joanna Stalnaker, the Paul Brooke Program Chair for Literature Humanities. “It is a vital work for our time, and a vital work for Lit Hum.”

Claudia Rankine SOA’93

“With this book, [my concern] was how to make something that is so consistently present, and yet fleeting and invisible, concrete,” she says. “It was a question of creating through prose a transparency that held moments that would be recognized by all, either as the aggressor or the receiver of the aggression.”

Citizen’s prose poems recount both verbal slights and intentional offenses. One longer essay considers the treatment of tennis superstar Serena Williams. A photograph of banal sunny suburbia grows teeth when you see the street sign reads “Jim Crow Road.” Most strikingly, there is a spread memorializing African Americans who have been killed by police, which gets added to with each printing. The 2020 edition read by fall term students includes the names of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, lending a bracing awareness of Citizen as a present, living document.

Rankine says she is honored to be included in the Core Curriculum, and that it’s not something she anticipated. But she does assume, in the act of writing, that her work will need a close reading. “That to me is pedagogy,” she says. “And that it should end up in an institution where close reading is valued, perhaps does make sense.”

She continues: “Of course I also teach, and I believe in the beauty of language and the importance of literature to the lives of all of us, or else we wouldn’t be in these institutions. I wouldn’t have spent almost my entire life with a book in my hand. I have the greatest regard for literature and for the culture — I do think the culture is what makes us.”

— J.C.S.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu