A Black History Month Exclusive: The College’s first Black graduate helped to unify South Africa.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

A Black History Month Exclusive: The College’s first Black graduate helped to unify South Africa.

Editor’s note: This feature first appeared in Columbia College Today’s Spring/Summer 1987 issue; it has been reedited and updated for historical clarity. The original article can be read here.

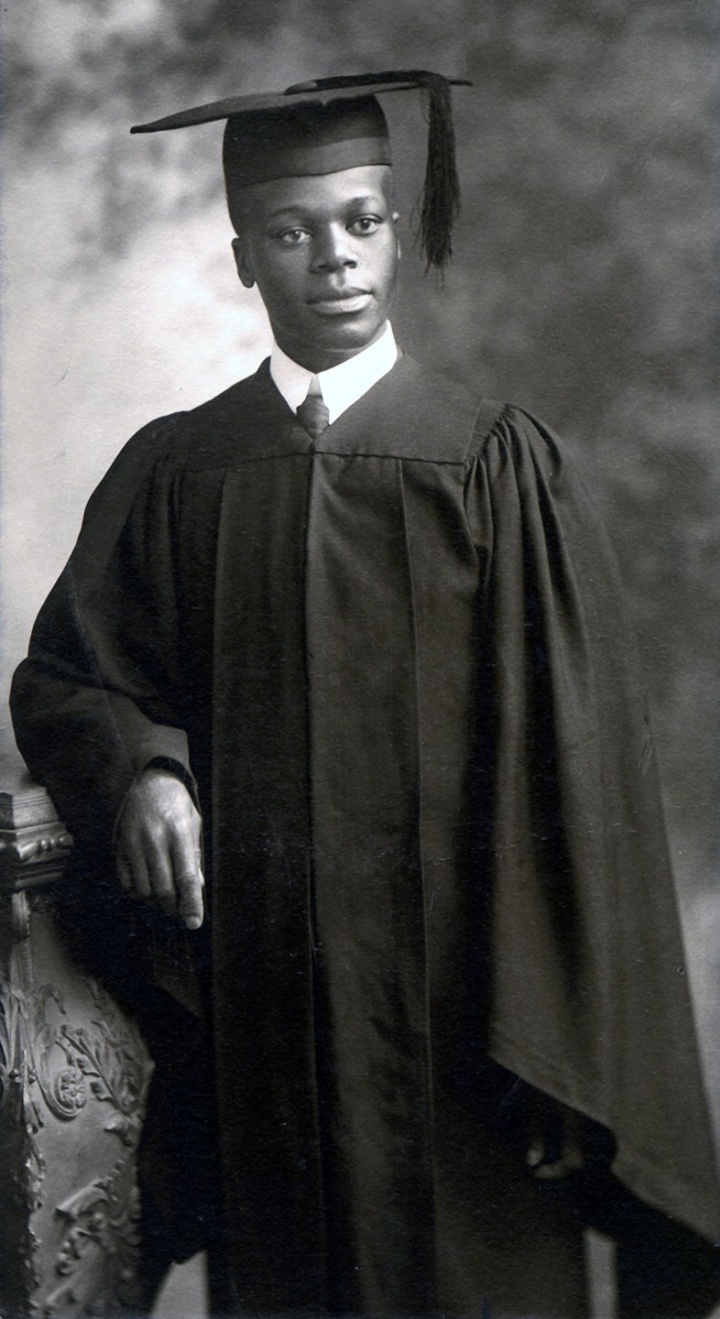

University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries

The creation of the organization that ultimately led the fight for racial equality in South Africa was, however, but one of many milestones in Seme’s remarkable life. After becoming the first Black graduate of the College nearly 115 years ago, he achieved renown as a prize-winning orator. In the 1930s, he served as ANC president for seven controversy-filled years. And toward the end of his life, he became a father figure to Black South African activists such as Anton Lembede and Walter Sisulu (one of Mandela’s cellmates during his imprisonment), who became important ANC leaders themselves.

Seme was born into a wealthy Christian family in South Africa on October 1, 1881, just after the proud Zulu kingdom to which his ancestors belonged was colonized by Britain. (He later said he was a Zulu aristocrat, though some historians dispute this.) His brilliant performance at his mission school attracted the attention of the American clergymen who ran it, and Seme was sent to study in the United States at Mount Hermon School for Boys in Massachusetts, where he received a classical education.

At the College, Seme focused on subjects related to Africa, Black people and the modern world. He took courses in anthropology, history and political science, anxious for scientific responses to the racist theories that were then current in both colonial Africa and overseas white society.

Seme was also deeply interested in Booker T. Washington’s vocational education programs for Black Americans. He visited Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1906, attended a speech Washington gave to Black businessmen in Atlanta the following year, and later wrote two admiring letters to the American educator.

Seme’s living arrangements while at Columbia served to put him in touch with Black reality in the U.S. There were no dorms when he entered the College, so he spent his four years of school living in Harlem, two on West 134th Street and two on West 135th — the first two blocks in the area where Black residents settled.

“My ambition,” Seme said after graduating, “has been to study the broad features of American life. I have tried to learn those things that will benefit my people and enable me to help them as I should. I enjoy hard work, and I have always desired to be in the center of things.

“This is why I came to Columbia. New York City is the cynosure of all American life; the greatest interests of the country are directed from this center. A glance through the city’s records is enough to convince any mind that Columbia is a force behind the throne in the greater movements of New York life.”

“I have tried to learn those things that will benefit my people and enable me to help them as I should.”

Outside the classroom, Seme was elected VP of the Freshman Debating Society and belonged to the Barnard Literary Society during his sophomore and junior years. As a senior, he won the prestigious Curtis Medal for Oratory with a speech on “The Regeneration of Africa,” which received national note. The oration was republished in both The Columbia Monthly and The Colored American magazine, and earned him an interview in The New York Times.

Seme combined a commitment to the enlargement of the horizons open to Black South Africans with a faith in its attainment through persuasion and loyalty to Britain, rather than confrontation. His ideal (much like Booker T. Washington’s) was the participation of African elites as junior partners in the white state and economy, not their overthrow in the name of the Black majority as a whole. He declared to the Times that his people “do not clamor for social equality, for that is an impossibility, but their aim and ambition is to be permitted to engage in international trade.” He also said he believed “the rule of the English to be a good thing for the African, bringing civilization and higher development.”

Seme in an undated photo.

Seme became the second Black South African to qualify as an attorney, and in 1910, just as South Africa was becoming an independent dominion, he returned home. Though Africans numbered three-fifths of the country’s population, in Johannesburg, where he settled, they were not allowed to walk on the sidewalks, much less vote. More discrimination lay in store: In the new all-white Parliament, proposals were afoot to end skilled mining jobs and prohibit land sales to Black people.

While quickly achieving repute in the legal profession (his first case, in which he secured a rare acquittal of a Black person accused of a crime against a white person, was widely noted), Seme threw himself into politics with characteristic energy. During 1911 he organized a series of meetings aimed at fusing the existing African political groupings, divided by provincialism and personalities, into one body, for which he drafted a constitution.

Seme’s greatest triumph came on January 8, 1912, when dozens of leading Africans from around the country assembled in Bloemfontein to consider the formation of a unified movement that would challenge the white government. Seme delivered the keynote. “In the land of their birth, Africans are treated as hewers of wood and drawers of water,” he roared. “The white people of this country have formed what is known as the Union of South Africa — a union in which we have no voice in the making of laws and no part in their administration. We have therefore called this conference so that we can together devise ways and means of forming our national union for the purpose of creating national unity and defending our rights and privileges.”

At the end of his fiery speech he moved for the creation of a South African Native National Congress. Cheers filled the hall, and the motion passed unanimously. The 30-year-old Seme became the first treasurer of the organization.

The establishment of the congress, which changed its name to African National Congress in 1923, was a remarkable achievement. It was the first national organization to give a voice to indigenous leaders in any African country and served as a model for others elsewhere. However, unlike later movements, it was neither militant nor mass-based. It was an alliance of African petits bourgeois and aristocrats who favorited a “qualified franchise” permitting only the propertied minority of Black citizens to vote.

While Seme’s great achievement was the creation of the ANC, his term as its president (1930–37) nearly destroyed it. He was elected by conservatives who were alarmed by the congress’s swing to the left in the late ’20s, when the growth of Black trade unions stirred the masses. Seme’s opponents, however, charged that he and like-minded party members preferred drinking tea in the parlors of white liberals to demonstrating in the streets.

Seme’s victory turned the ANC away from the African workers and peasants, the vast bulk of the Black population, and launched it into a self-destructive spiral of petty politicking. He revealed a disturbing will to dominate, sacking four colleagues on the national executive committee and stacking an ANC convention to ensure his reelection. While autocratic within his organization, toward the authorities he displayed a fawning attitude that infuriated government opponents, Black and white. The collapse of ANC structures during his presidency, both at grassroots and national levels, led other leaders to insist on his replacement at the 1937 Silver Jubilee convention of the organization he had founded.

Seme did not, however, remain fixed in his views. In the 1940s, when a revitalized ANC became more assertive, he adapted to the times. He contributed to a 1942 manifesto in which the congress came out for majority rule for the first time.

Indeed, with hindsight, Pixley Seme may well prove to have been one of Columbia’s most influential sons. When he died in 1951, it marked the end of the germinal phase of African politics in South Africa, and the opening of a period of popular mobilization. His funeral, conducted by the Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg, Ambrose Reeves, drew a crowd of 2,000, including the entire ANC national executive committee. After the service, the committee met to plan a campaign of civil disobedience, which in 1952 was to transform the congress from an elite coterie into a mass movement.

Later, in the 1980s and ’90s, the anti-apartheid movement transcended its South African origins to become an international cause, and its success was a landmark achievement in the fight for human rights. Today, the ANC remains the governing party of the Republic of South Africa.

As South African historian Mary Benson concluded of Seme’s legacy: “If Seme failed personally in the 1930s, his earlier achievement is what matters more. The foundation of the ANC was a positive act of unification rare in South African history.”

At the time of writing in 1987, Craig Charney was preparing a doctoral dissertation on Black South African politics at Yale University and had been a Johannesburg correspondent for The London Times Higher Education Supplement. Today he is a pollster and political scientist for Charney Research, with more than two decades of experience in over 45 countries. Research assistance on the original article was provided by Associate Editor Myra Alperson.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu