Mike Wallace ’64 is the “radical historian” behind the Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicles of New York City.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Mike Wallace ’64 is the “radical historian” behind the Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicles of New York City.

Jörg Meyer

Wallace’s reply is almost automatic: “Except that it’s not.”

I should have known better. If there’s anyone who can take the long view in these incredibly turbulent times, it’s Mike Wallace, who has devoted his life and career to unpacking the essential lessons from centuries of American history. There is no succinct way to summarize Wallace’s accomplishments, but let’s try anyway. He is a Distinguished Professor of History at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the CUNY Graduate Center. He is the founder or cofounder of a series of influential historical projects, including the Radical History Forum, the New York Public History Project and the Gotham Center for New York City History. He is the recipient of a long, long list of honors and prizes, beginning with a Columbia University Presidents Fellowship in 1961 and ending with the first Federal Hall Medal for History in 2017.

And, yes, there’s the Pulitzer Prize-winning book that is widely regarded as the greatest and most authoritative history of New York City to date.

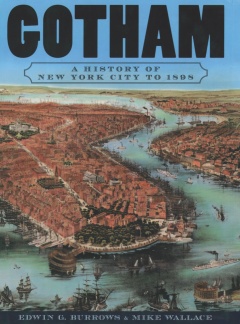

Wallace authored Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 alongside fellow historian Edwin G. Burrows in 1998, a stroke of timing that coincided with the 100th anniversary of New York’s consolidation into five boroughs. And if that subtitle sounds almost comically ambitious, it has nothing on the book itself. Gotham is the rare work that is helpfully described in both page count (1,408) and pounds (4.73).

But now, reflecting on Gotham and its sequel, Wallace doesn’t mention the starred reviews or the Pulitzer. His measure of the project’s success is a simpler one: The sheer number of readers who told him they’d enjoyed reading a history book. “That’s the indispensable criteria,” Wallace says. “If you don’t enjoy it, you’re not going to remember it. You’re not going to finish it. You’re not going to believe it.”

A bird’s-eye view of the City of New York, ca. 1884.

Library of Congress

It’s a pragmatic philosophy that happens to be squarely in line with what attracted Wallace to the subject of history in the first place. Entering Columbia College in 1960, at 18, Wallace was at just the right time, and in just the right city, to fall in love with the subject — though that wasn’t the original plan. “I was going to be a doctor. My mother was very clear on that,” he says, laughing.

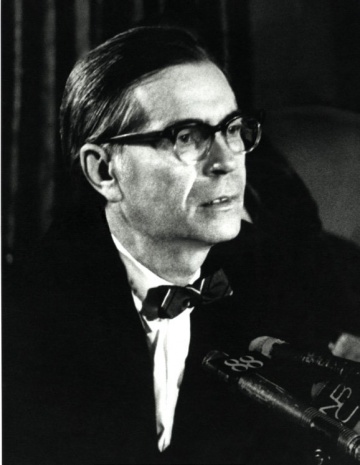

Wallace’s mentor, Richard Hofstadter GSAS’42, in 1968.

Columbia University Rare Books & Manuscript Library

In addition to his personal and professional relationship with Hofstadter, Wallace’s young career was defined by another key event: his participation in the student strike of 1968, which famously resulted in the occupation of campus buildings and their subsequent storming by the NYPD. Wallace was elected to the Strike Coordinating Committee — in “the more moderate faction,” he says — though Hofstadter opposed the protests. “The remarkable thing is that we remained friends and colleagues despite the tempestuous ’68 moment,” says Wallace. Splitting his time and his influences between a respected (but relatively orthodox) historian and an exciting (but relatively unstable) political movement put Wallace in a unique position to bring both intellectual rigor and revolutionary spirit to the field of history. Wallace’s dissertation, which was on the nature of American political parties, began with a straightforward premise supported by Hofstadter: Political parties are, broadly, a net good for the United States. But Wallace’s experience on the strike committee, and his interactions with other young historians who were eager to challenge accepted norms, pushed his research toward those who often went ignored in historical discussions: “People who were excluded by the two-party system — and were meant to be excluded.”

By the early 1970s, Wallace had emerged as one of the world’s premier practitioners and proponents of “radical history,” which sought to understand historical events through previously overlooked lenses like gender, race, sexuality and class. “You began to have Black activists [looking at published histories] and saying, ‘What the f--- is this?’ So Blacks get added into the picture. Then come the women. ‘Oops, you left out half of the population.’ But by adding individuals or groups into the picture, you’re also left with the necessity of confronting the white reaction to this. You’re confronted with the necessity of analyzing and understanding racism. So it wasn’t just addition. It was transformation.”

The concept of “radical history,” which has become central to the approach of many modern-day historians, was revolutionary at the time, and Wallace devoted much of his career to practicing and spreading it. In 1971, he took a job at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice to teach police officers the history of American justice. In 1973, he became a co-founder and director of the Radical History Forum, and was the editorial coordinator of the Radical History Review through the mid-80s. He published a series of essays, eventually collected into a volume called Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory, that explored how and why American history is (often misleadingly) packaged for the general public. And in 2000, he established the Gotham Center for New York City History, which aims to “increase scholarly and public understanding of New York City’s rich and living past.”

Wallace’s inclusive, pragmatic, forward-thinking approach to history, and to New York City in particular, proved uniquely timely when — just a year after the Gotham Center was founded — the World Trade Center was attacked on September 11, 2001. In his book A New Deal for New York, which was published just a year after 9-11, Wallace made the provocative case that the rebuilding necessitated by the attack on the World Trade Center was also an opportunity to rethink the future of New York City, with a government-funded program that would tackle looming crises like breakdowns in mass transit and unaffordable housing.

“History doesn’t guarantee anything. But my default position is that New York will bounce back.”

Today, it’s impossible to read A New Deal for New York without drawing parallels to the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus has been a disruptive and devastating force across the world, but few American cities have been affected as dramatically as New York, where the population density and public transit systems pose unique challenges for the virus’s potential spread. As countless small businesses close their doors and a not-insignificant portion of residents vacate the city entirely, it’s easy to wonder: Is there really a way that a post-pandemic New York City can thrive? Can it even recover?

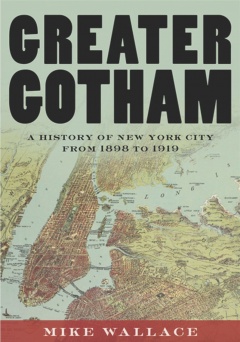

NYC views, past and present (below).

Wikipedia Commons

For someone with such a depth of knowledge about New York City’s past, Wallace is clearly, rigorously invested in the city’s present and future. This is both the danger and the joy of asking Mike Wallace about New York City: You can ask a simple question, but there are no simple answers. If you ask what it was like to grow up in New York City, he’ll patiently explain that it was a time when there was very real debate about whether Queens even counted as New York City. And if you ask what neighborhood he lives in now, you’ll get an elegant mini-treatise on the fluctuating boundaries of Park Slope that weaves in fluid social dynamics and the history of the railroad depot.

For all his knowledge and love of the city, Wallace is currently only a part-time New Yorker. Wallace’s wife (and sometimes collaborator), celebrated Mexican writer Carmen Boullosa, is a distinguished lecturer at CUNY’s Macaulay Honors College, but the couple split their time between New York and Mexico City. “At a time when bi-nationalism is not seen as desideratum, we are, I guess, an example of possibilities,” he says. Wallace has taken to his second home city, though he admits his Spanish is rusty enough that he eventually bows out of the frequent salons with Mexican writers, artists and intellectuals he and Boullosa host at their home. “They’re very welcoming to me at the dinner table until the third glass of wine — at which point English is out the door, and so am I.”

Fortunately, there’s no shortage of work to occupy him. There’s a third volume of Gotham on the way, which will pick up where Greater Gotham left off in 1919 and stretch to the end of WWII. “Fortunately, the logic [of the historical narrative] is pretty clear: ’20s boom, ’30s bust, ’40s war,” Wallace says. Each Gotham book is a titanic undertaking, and “nothing about this project happens quickly,” he says. The book won’t write itself, so Wallace has focused all of his energy on it, retreating almost completely from the crowded roster of events that defined him as a busy public intellectual in the early 2000s.

To the immense relief of anyone fearing another lengthy gap between books, he confirms that a not-insignificant chunk has already been written. Still: Gotham was published in 1998, when Wallace was 56; Greater Gotham was published in 2017, when Wallace was 75. If the third volume required the same amount of time, it would be published in 2036, when Wallace would be 94.

There is no delicate way to ask the obvious question that hovers around the third book, so I’m a little surprised when Wallace himself brings it up with a matter-of-fact shrug. “On this one, I’m under the time pressure of death,” he says. “But I’ve always felt that.”

And so, barring that final and unwelcome stopping point, the work continues. In New York or Mexico City, Wallace wakes up, sits down at his desk, and diligently goes back to assembling his surpassingly comprehensive history of the greatest city in the world. In fact, this very conversation is an unusual break from his routine. “You’re the only person that I’ve done an interview with. My rule is: I don’t deviate from the historical work for anything,” he says, pausing thoughtfully. “But this is the historical work.”

Scott Meslow is a writer, editor and critic for publications including GQ, Vulture, POLITICO Magazine, The Atlantic and The Week. His first book, From Hollywood With Love — an oral and visual history of Hollywood romantic comedies in the ’80s and ’90s, and the genre’s resurgence in the streaming era — will be published in early 2022. He lives in Los Angeles.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu