Shakespeare, literary architect, performs a gut renovation and creates a classic.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Shakespeare, literary architect, performs a gut renovation and creates a classic.

The execution of the conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot: Claes Jansz Visscher’s contemporary etching depicts Londoners gazing from rooftops, windows and streets as four Gunpowder plotters are drawn to the site of execution.

Shapiro’s latest foray into the Bard’s works, The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 (Simon & Schuster, 2015), takes a radically new look at the so-familiar author. Shapiro admits that, like most scholars, he saw Shakespeare as mainly an Elizabethan writer; the playwright grew to prominence during the “Gloriana” era’s gradual decline. But three of Shakespeare’s best-known tragedies — King Lear, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra — were written in a single, extraordinary year early in the reign of Queen Elizabeth’s successor, King James. James had actually named Shakespeare and his players the “King’s Men,” his official theater company, by 1603.

In The Year of Lear, Shapiro describes how Shakespeare’s Lear was written in the shadows of England’s Jacobean gloom, as London was beset by plague and the bitter aftermath of treason. He shows us Shakespeare’s efforts to renovate an older dramatic work (King Leir, performed by the Queen’s Men) and the subtle literary changes he used to make it modern.

James Shapiro ’77

MARY CREGAN

— Rose Kernochan BC’82

King Lear draws so extensively from King Leir that Shakespeare’s indebtedness couldn’t have come solely from what he recalled from acting in it or seeing it staged years earlier, however prodigious his memory. The profusion of echoes confirms that reading the recently printed edition proved to be the catalyst for the play now forming in his mind. King Leir’s survival in turn allows us a glimpse of Shakespeare as literary architect — performing a gut renovation of the old original, preserving the frame, salvaging bits and pieces, transposing outmoded features in innovative ways.

Demand for new work was as insatiable at the public theaters as it was at court. Because Elizabethan and Jacobean spectators expected to see a different play every day, playing companies had to acquire as many as twenty new plays a year while rounding out their repertory with at least that many older and reliably popular ones. Attendance would eventually drop when familiar plays began to feel stale, and the task of breathing fresh life into those staged at the Globe would almost certainly have fallen to Shakespeare. While we know that Shakespeare wrote or collaborated on as many as forty plays, we’ll never know how many old ones he touched up. We do know (by comparing early and later versions) that he updated his earliest tragedy, Titus Andronicus (c. 1590–92), adding a poignant new scene in which a maddened Titus tries to kill a fly with a knife. Some scholars believe he was also the author of the speeches added to that old chestnut The Spanish Tragedy (c. 1587), by Thomas Kyd. For all we know, over the course of his career Shakespeare might have refreshed dozens of his company’s plays in this way and was as practiced as anyone at giving a cold, hard look at an old favorite, recognizing what now felt a bit off or what trick had been missed. His ability to pinpoint what was flawed in the works of others was one of his greatest gifts, though not one we know enough about nor celebrate today. It was a talent closely allied to his habit of relying on the plots others had devised rather than inventing his own.

Shakespeare had a talent for recognizing the untapped potential of resonant words, even the simplest ones.

Before he picked up a copy of the old Leir, Shakespeare was already familiar with several versions of this story. He may have first read about Lear’s reign in his well-worn copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland. He had also read Edmund Spenser’s brief account of it in The Faerie Queene and had come across retellings of the tale in both Mirror for Magistrates and Albion’s England. He might have even consulted Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Latin version of Lear’s story from which all these other versions derive. Yet scholars who have painstakingly compared King Lear with each of these sources conclude that as voracious a reader as Shakespeare was, and as much as he might have drawn on these and other versions of the story for particular details, it was King Leir that he worked most closely from — and against.

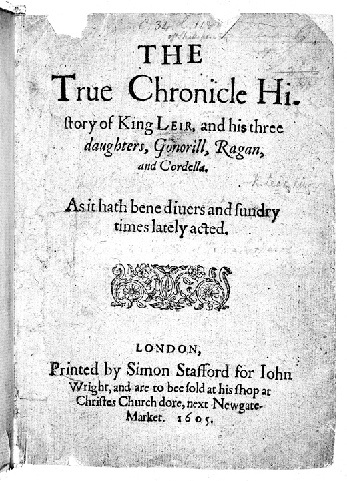

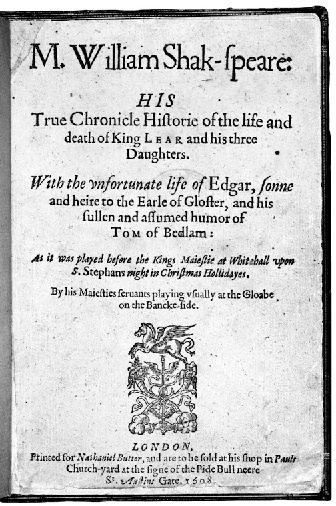

That “against” would have been obvious to anyone who compared the title page of King Leir with that of the first printed version of Shakespeare’s play, a quarto that appeared in London’s bookstalls in early 1608. Ordinarily, considerably more time passed before Shakespeare’s playing company turned one of his plays over to a publisher; a delay of a couple of years was closer to the norm for his Elizabethan plays, and as yet not a single one of his Jacobean plays had been printed. So it’s doubly surprising that Shakespeare’s play was entered in the Stationers’ Register in November 1607, less than a year after it was staged at court. The full title of the 1608 quarto of Lear feels like a riposte to the title page of the old play, which had read in full: “The True Chronicle History of King Leir, and his three daughters, Gonorill, Ragan, and Cordella, As it hath been divers and sundry times lately acted.” This time, the publisher not only names the play’s author but — and this was new — gives England’s best-known playwright top billing in large font. The play is emphatically Shakespeare’s: “HIS” is in capital letters and even gets a separate line. The main title that follows is much the same as the old play’s: a “True Chronicle History of the life and death of King LEAR and his three Daughters.” It too claims to be the “True Chronicle History” rather than distinguishing itself, say, as the “True Tragedy of King Lear.” But the title page goes on to distinguish the new play from the old one by emphasizing that it is about both the lives and the deaths of Lear and his three daughters. It also offers more than its predecessor: a secondary plot about “the unfortunate life of Edgar, son and heir to the Earl of Gloucester, and his sullen and assumed humor of Tom of Bedlam.” It would be the first and last time that Shakespeare ever included a parallel plot or subplot in one of his tragedies.

He needed it, because it was immediately clear that the story in Leir lacked counterpoint, a way to highlight Lear’s figurative blindness by juxtaposing it with something more literal. It would also enable him to critique the very notions of authority and allegiance at the heart of the main plot. Shakespeare’s genius was first in discovering the perfect foil to this story and then in almost seamlessly weaving it into the narrative of Lear and his daughters. He found it in a tale about a blinded father and his two sons, one virtuous, the other evil, that he had read years earlier in the most celebrated of Elizabethan prose romances, Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, published in 1590. Sidney’s striking image of a blind and suicidal old man being led to the edge of a cliff by his good son, both of whom appeared “weather-beaten” and in rags, had clearly stuck with Shakespeare. Sidney’s words had also stuck with him, especially what the old man tells his son as he prepared to leap to his death: “Since I cannot persuade thee to lead me to that which should end my grief, and thy trouble, let me now entreat thee to leave me. . . . Fear not the danger of my blind steps, I cannot fall worse than I am.” It took very few strokes for Shakespeare to make this scene central to his new play. In Sidney’s story, the suicidal old man had been a king who was blinded and stripped of his kingdom by his bad son; it was easy enough for Shakespeare to turn him into an earl and a follower of King Lear, then have his evil son implicated in both his undoing and blinding.

Title page of the Quarto of King Leir (1605)

© THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, C.34.K.18, TITLE PAGE

What seems inevitable in retrospect was anything but: merging plots from a play and a prose romance to form a double helix, firmly interlocked and mutually illuminating. Shakespeare also saw that Lear’s elder daughters could vie for Edmund’s affections while the good son, now named Edgar — in Sidney he eventually becomes king — could emerge as something of a hero. All this could replace the meandering and unsatisfying middle of King Leir that Shakespeare would all but scrap. It also solved a major problem of the old play. The anonymous author of Leir had been content to build to a somewhat wooden reconciliation scene between father and daughter, one that failed to pack much emotional punch. Shakespeare’s Lear would substitute for that not one but two powerful recognition scenes, the first between Lear and Cordelia, the second, soon after, where the two plots converge, between the mad Lear and the blind Gloucester. It’s debatable which of the two is the most heartbreaking scene in the play.

Title page of the Quarto of King Lear (1608)

STC 22292, HOUGHTON LIBRARY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

As Lear’s division of the kingdoms spills into a psychologically complex drama of two families, motives become more complicated and unsettled. Does Lear go mad because he has foolishly divided his kingdoms or because of his ruinous relationship with his daughters? It’s impossible to tell, because in scene after scene the political, the familial, and ultimately the cosmic are so deeply interfused. The fortunate survival of Leir enables us to see the sheer craftsmanship involved in all this. Yet it also needs to be acknowledged that Shakespeare didn’t always get the parts to fit together quite so neatly. As keen as he was to work in that image of a suicidal man led by his son to the edge of a cliff, audiences have wondered ever since why Edgar, disguised at this point as Poor Tom, doesn’t simply reveal himself to Gloucester (the excuse that Shakespeare gives Edgar, that he is trying to cure his father by putting him through all this, feels lame). And the French invasion of England, so central to Leir, sits uneasily in Shakespeare’s version, a part of the old play that he did his best to integrate but that ends up feeling confused and confusing. He himself — or if not him, members of his company — would go back and tinker with the problematic invasion, though with only partial success.

Rather than rely entirely on his own considerable vocabulary, Shakespeare somewhat surprisingly recycled what he could from the language of the old play. He had a talent for recognizing the untapped potential of resonant words, even the simplest ones. Take “nothing.” The word appears often in Leir, even as part of a raunchy joke (Gonorill and Ragan laugh about women getting stuck with a man “with nothing” — that is, one who is castrated, so has no “thing” [2.3.22–23]). But it is never used with any particular emphasis in that old play, not even when the French king asks Cordella whether Leir has “given nothing to your lovely self ?” and she pointedly replies, “He loved me not, and therefore gave me nothing” (2.4.71). Each Shakespeare play has its own distinctive music and, not unlike a symphony, its themes are established at the outset. At an early stage of recasting the old play, Shakespeare seems to have decided that “nothing” would be the motif of Lear’s score. The first time we hear the word is after Lear demands of Cordelia what she “can say to win a third more opulent” than her sisters, to which she replies: “Nothing, my lord.” Lear, stunned by her response, hurls the word back at her: “How? Nothing can come of nothing” (1.78–81). This first “nothing” takes on a life of its own, reverberating with greater force from then on, punctuated by this pointed exchange between Lear and his Fool:

LEAR. This is nothing, fool.

FOOL. Then, like the breath of an unfee’d lawyer, you gave me nothing for’t. Can you make no use of nothing, uncle?

LEAR. Why no, boy. Nothing can be made out of nothing.

(4.122–26)

Shakespeare would also, and brilliantly, use “nothing” to suture together the Lear and Gloucester plots. Even as Cordelia’s initial response to her father are the words “Nothing, my lord,” so too, in his first exchange with his father, Edmund, when asked by Gloucester about the contents of the letter he has hastily hidden, replies, chillingly, with the very same words: “Nothing, my lord” (2.31).

In Shakespeare’s hands “nothing” becomes a touchstone — and the idea of nothingness and negation is philosophically central to the play from start to finish. Cruelly, by play’s end Lear turns out to be right: nothing does indeed come of nothing, only not in the way he first meant. Early on in imagining his version of Lear’s journey, Shakespeare saw that what began with that first “nothing” must end with Lear left with nothing, except, perhaps, the knowledge that his dead and beloved daughter will never return — “never, never, never” (24.303). In the interim the words “never” and “nothing” recur more than thirty times, the word “no” more than 120, and “not” twice that often. The negativity is reinforced by the sixty or so times the prefix “un” occurs, as characters are “unfriended,” “unprized,” “unfortunate,” “unmannerly,” “unnatural,” and “unmerciful.” Call it what you will — resistance, refusal, denial, rejection, repudiation — this insistent and almost apocalyptic negativity becomes a recurring drumbeat, the bass line of the play.

From THE YEAR OF LEAR by James Shapiro. Copyright © 2015 by James Shapiro. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu