Professor Robert E. Harrist Jr. GSAS’81 delights in the study of art in all its forms.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Professor Robert E. Harrist Jr. GSAS’81 delights in the study of art in all its forms.

It is August, a traditional time of respite for academics, but Robert E. Harrist Jr. GSAS’81 is hard at work. The Jane and Leopold Swergold Professor of Chinese Art has just returned from teaching an Art Humanities/Music Humanities immersion program in Paris and is now preparing to travel to China to give a talk about inscriptions on Mount Tai (“When you go to China you don’t just climb a mountain, you read it,” he explains).

Harrist, 63, is one of the world’s foremost experts on Chinese painting and calligraphy — and one of the few who did not grow up speaking Chinese — and he knows the subject of this conference particularly well; it is the same as his 2008 book, The Landscape of Words: Stone Inscriptions from Early and Medieval China. The intense preparation has to do with giving a professional-level, public talk to a mostly Chinese audience, in Chinese — not something he ordinarily does.

JÖRG MEYER

“Words you think you know how to pronounce you might be mispronouncing because of the tones,” he explains. “All those years you’ve been meaning to look it up but haven’t quite gotten around to it.” Now he is spending hours practicing saying those words.

Only days earlier, Harrist was in Paris speaking fluent French. He can also read Japanese and speak it conversationally. Yet he claims he is “not good at all at foreign languages.” He plays Bach, Schubert and Chopin quite well on his Steinway grand, although he says, “I play at the level of an advanced beginner, and have for about 45 years.” He has thought of trying to teach Music Humanities: “It’d be wonderful, but I don’t think I could do it well. I barely know enough to teach Art Hum!” In fact, he has a degree in music in addition to an uncharacteristically deep knowledge of Western art.

Harrist’s devotion to various art forms — he is also a balletomane who has written for Ballet Review — is part of an overall enthusiasm for life’s ornaments, from the literally monumental to the quotidian. He notices details and delights in them. One might guess that his varied expertise and talents make him intimidating, but his humbleness as well as joie de vivre have won him many friends as well as made him a popular teacher. “I’ve never known anybody who takes such deep and great pleasure in life — in works of art, other people, the weather — you name it,” says William Hood, visiting professor at the Institute of Fine Arts of NYU, a former colleague and longtime, close friend of Harrist. “His whole life is fueled by joy, a capacity to be awed by things most people wouldn’t even notice.”

“I still can’t believe I get paid to do this,” Harrist says. “Can you imagine anything better than being paid to look at sculptures of Michelangelo and talk about them with smart, young people? It’s impossible to describe how fortunate people in my position are — a senior position at a place like Columbia University. We are some of the most privileged people on earth.”

“Can you imagine anything better than being paid to look at sculptures of Michelangelo and talk about them with smart, young people?”

Harrist grew up in the small town of Rockport, Texas, on the Gulf Coast. Adopted as an infant, he was the son of a refrigerator and air conditioner repairman and a homemaker. Instead of growing up hearing about when he was born, Harrist heard his parents speak of “when we got you.” “It was like being parachuted into this world,” he says. He describes his beloved hometown as a cross between To Kill a Mockingbirdand It’s a Wonderful Life. As a kid, he went hunting (“deer, quail, jackrabbit — you name it, we’d shoot it”) and rode on a roundup of his uncle’s cattle.

He also, inexplicably, yearned to learn to play the piano. “In our house, the first and only notes of classical music ever played were by me. I don’t know how I found my way to them,” he says. When his grandmother came into some money, she bought a piano. He took lessons and “got saddle sore from practice ... Whatever crazy notions I had, I was always encouraged and supported,” he says. “My parents truly were angels.”

One of those notions, stuck in his head from the time he was little, was to live in New York. “Everything I knew about New York I got from I Love Lucy. So from my perspective, everyone was funny and lived in cozy apartments and went down to the club at night. And except for going down to the club at night, it all came true,” he says, adding, “Well, I guess I could go down to a club at night ...”

After starting at Del Mar College in Corpus Christi, Texas, Harrist studied music at Indiana, where he played the oboe, until he took his first art history class and changed course, adding an art history major to his music major. He went on to a master’s in art history from Indiana (1978), where he wrote his thesis on Matisse, still his favorite artist. During graduate school he was enchanted by a survey course of Chinese art, in particular the calligraphy. He says he may have appreciated it because his eye had been trained to look at abstract art.

The professor, Susan Nelson, discouraged him from pursuing the field, as the language is so difficult. “You’ll never curl up with a Chinese novel,” she told him. He was not dissuaded and later, after he did master the language, Harrist made his own mark in the field by examining, in a holistic manner, the inscriptions carved into mountain faces at thousands of sites across China. “Visitors to China, tourists and scholars alike, frequently see these giant inscriptions, but no one before Bob fully realized how phenomenally significant this practice is as a defining characteristic of the Chinese cultural mindset,” says Jan Stuart, who met Harrist in graduate school and is the Melvin R. Seiden Curator of Chinese Art at the Freer and Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington D.C.

“In his path-breaking work [The Landscape of Words], Bob combined perspectives from these seemingly disparate fields, calligraphy, landscape studies and religion,” Stuart continues. “And he showed us the unique way in which the Chinese have orchestrated their experience of nature by turning the raw material of stone cliffs — mere physical spaces — into landscapes that convey deep values reflective of religious practice, political history, social engagement and art.”

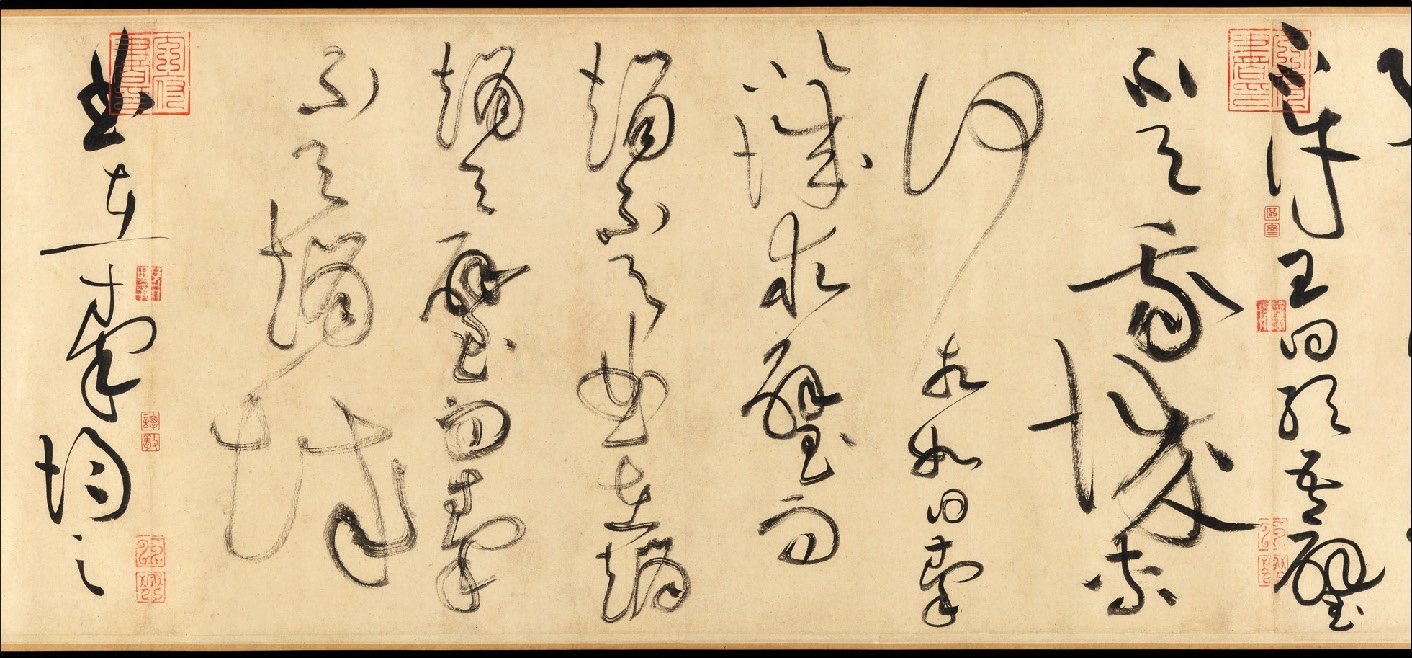

Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru, ca. 1095

Huang Tingjian (Chinese, 1045–1105)

Handscroll; ink on paper; 12.75 in. x 59 ft. 9 in.

(32.5 x 1822.4 cm)

Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988 (1989.363.4)/span>

“It was because of calligraphy that I decided to study Chinese art. I fell in love with it before I had started to learn Chinese, and although I encourage everyone to study Chinese, it’s possible to enjoy calligraphy deeply without a knowledge of the language. The text of this scroll consists of the biographies of two ancient worthies, but a connoisseur of calligraphy would concentrate on the structure of the characters and the energy of brushstrokes, not on the content of the text. It’s sometimes said that the linear patterns of Chinese calligraphy can be appreciated in the way we appreciate abstract art. That’s true, but unlike, let’s say, a painting by Jackson Pollock, calligraphy has to conform to rules: no matter how wild or abbreviated the characters, they have to be written from top to bottom following a prescribed order of strokes. In this scroll you can see traces of how time passed as the calligrapher worked. In the next to last column on the left, the brush was going dry, and before writing the final column the calligrapher dipped the brush in the jet black ink.”

In 1978, Harrist arrived at Kent Hall for an intensive master’s in East Asian studies, then continued his art history education with a Ph.D. in Chinese art and archaeology from Princeton in 1989. He joined the faculty at Oberlin in 1987, where he remained for a decade until a position opened at Columbia. He received an Award for Distinguished Service to the Core Curriculum from the Heyman Center for the Humanities in 2004 and a Lenfest Distinguished Faculty Award in 2006.

“We have been lucky to have Bob share his expansive appreciation of art with generations of Art Hum students,” says Dean James J. Valentini. “Bob is known among students for his incredible knowledge as a professor and for encouraging them to ‘articulate the obvious’ when describing art. His passion for sharing artistic sensibilities does not stop with the visual arts. While teaching in the combined Art Humanities/Music Humanities program this summer in Paris, Bob often used his talent on the piano to play for his class the pieces they were studying in Music Hum.”

Harrist chaired the art history department from 2007 to 2011 and was a beloved leader, according to Stephen Murray, the Lisa and Bernard Selz Professor of Medieval Art History, who has been on the faculty since 1986. “He has a generosity and a civility that is so rare in academia,” Murray says. “He considered the operation as a privilege, as the creation of an ideal community of teachers and scholars, not as imposing rules and restraints. He once asked me, ‘What can I do to make your life better as a teacher?’ Has any chair anywhere ever said that?”

In New York, while on sabbatical from Oberlin in 1993, Harrist met his wife, Weizhi Lu, a Spanish and Chinese teacher at an NYC public high school. They now have a 16-year-old son, Jack. “I’m from South Texas and my wife is from the south of China and together we produced a native New Yorker,” Harrist says. He notes how different Jack’s upbringing has been from his own: “I did not set foot in a major museum until I was 20, in Chicago. We just didn’t have anything like that in a small town. Being able to go to the Met — that would have been the most unbelievably dazzling, glamorous thing you could imagine.” ( Jack prefers to go to Yankees games, so Harrist has expanded his interests to include baseball.)

Nearly two decades after moving to New York, the thrill of seeing art at the Met has not worn off. Harrist goes to the museum usually once a week, often with his colleague and friend Hood. In the course of teaching art survey classes, both have lectured on Bruegel’s The Harvesters “a gazillion times,” Hood says. Yet one day they stopped to look at it together and, as Hood describes, “The next thing we knew, 1½ hours had passed.”

Another day, Harrist led Hood upstairs to look at a late-period Monet water lilies. Hood says he himself had always been prejudiced against the Impressionists, but that Harrist took him up close to the painting to examine how the color of the paint interlaced with the texture on the painting. “It was astounding. I’d never seen Monet before,” Hood says. “That’s the type of scrutiny that very few people are capable of. He’s capable of deep scrutiny, of any period, of any style, of any culture. Bob is so dedicated to the life enhancement that can come to a person who’s willing to put the effort into engaging with a work of art.”

Princesse de Broglie, 1851–53

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867)

Oil on canvas 47.75 x 35.75 in. (121.3 x 90.8 cm)

Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.186)

“I like to end Art Hum tours with this portrait, which I think is one of the most beautiful paintings in the museum. It stops us in our tracks, above all because of the seemingly photographic precision of the image. Have you ever seen a more beautiful blue satin dress? You can get lost in simply admiring what a master of oil painting Ingres was. But the painting is full of subtle distortions and weird adjustments of reality. The face has the geometric regularity of an archaic Greek statue, and Ingres never let actual bone structure get in the way of painting elegant bodies. Try to figure out how the right wrist is attached to the arm. Most of the surface of the painting is smooth and glossy, but pieces of jewelry are painted with thick encrustations of paint that stand up in relief. The Princesse de Broglie died at 35, seven years after Ingres finished her portrait. This fact has nothing to do with the origins of the painting — neither the princess nor Ingres could see into the future — but it’s hard not to let this knowledge of her fate cast a retrospective melancholy over this quiet, serene image.”

Which is why Harrist declares Art Hum his favorite course. He teaches it nearly every year, alongside Chinese Art 101 and a graduate seminar or lecture, often on Chinese painting or calligraphy (a rare offering at U.S. schools). Even his graduate classes on Chinese art, however, are geared toward the non-specialist; he encourages students of European art to participate. “He’s a rigorous looker. He can look at a single work of art for hours and continue to come up with fresh observations,” says Joseph Scheier-Dolberg GSAS’12, assistant curator of Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Met and a grad student of Harrist. He recalls the day when Harrist put up a slide of an ornamental detail in his Chinese art class and asked if anyone could identify it. Nobody could. It was a pattern from a mosaic on the subway platform at 116th Street. “He never turns his eye off. He’s always looking,” Scheier-Dolberg says.

Harrist says that getting people truly to look is a main job in art history: “The older I get, the more I find myself focusing on that,” he says. “It’s incredibly hard to look at things. You think you’re seeing things but really your eye is just drifting.” Recently he has been examining the ways of the late Meyer Schapiro ’24, GSAS’35, the preeminent art reviewer, historian and Columbia professor. Schapiro believed that to examine a work of art closely, it helped enormously to draw it. To that end, Harrist himself took up drawing about the time he became chair of the department and enrolled in classes at a studio downtown. As chair, he secured funds for students to take life drawing classes.

He says about art, “I love it more every year. Sometimes I feel I’ve only recently begun to see things myself. It makes me wonder what I was doing all those years and all I missed.”

Despite his wide-ranging expertise, Harrist is repeatedly described as low-key, humble, open-minded and humorous. “He has so much knowledge and knows all these facts, but you can go out with him and just have fun,” Stuart says. She says there’s nobody she’d rather go to a concert or ballet with than Harrist.

Nancy Zafris GSAS’79, friends with Harrist since meeting at International House in 1978, describes attending a Matisse cutout exhibition at MoMA last December: “Bob was talking to us and pretty soon there was a little cluster of people listening and following us,” Zafris says. “He was so clear and insightful and interesting, and so accepting of other people.Two older women were there from out of town and he went off with them to look at something. He was very excited about what they had to say.”

Zafris says Harrist “finds a lot of pleasure in things other academics might disdain; he doesn’t disdain anything.” She mentions his watching a Facts of Life sitcom marathon with her when he was in grad school at Princeton and his finding it “quite delightful.” On a visit to New York in October 2014, she and Harrist went to see the New York City Ballet and then went straight to a Bill Murray movie.

Susan Boynton, chair of the music department and Harrist’s teaching partner for Art Hum/Music Hum this past summer in Paris, noted that Harrist has so many friends that he was invited out or to someone’s home nearly every night. “He can relate to people really easily. There’s not a grain of snobbery in him,” Boynton says. Those traits also make it easy for Columbia students to relate to him, she says, and contribute to his popularity.

It is the students, Harrist says, who keep him inspired: “I’m always looking for new things to say ... it’s through teaching that I continue to engage with the works.”

Students of Harrist appreciate that he gets to know them and listens to them. As part of Art Hum in Paris, on a visit to the Louvre, Harrist told the class first to spend time walking around Michelangelo’s Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave sculptures, and for the students to note what interested them. Then, in the midst of the crowds, Harrist led each student around the sculptures individually for a few minutes to discuss the work. “He asked us what stood out to us and took us over to that part of the sculpture and talked about it,” says Ben Libman ’17. He says each student did as much talking as the professor: “It was very collaborative. He really embraces the seminar environment.”

“He would incorporate your strengths or interests to bring out the best in you, and for the class,” says Kaitlin Hickey ’18. She says Harrist picked up on her knowledge of mythology, and when the class was at the Medici Fountain in Luxembourg Garden, he asked her to say a bit to the rest of the class about the depiction of Leda and the Swan behind the fountain.

Indeed it is the students, Harrist says, who keep him inspired. “If I were living out in the mountains and not at a university, it’d be hard to stay interested,” he says. “I’m always looking for new things to say — even though they’ve never heard it before, I have, and they can sense a certain staleness if you don’t continue to revise and discover new things. So it’s through teaching that I continue to engage with the works.”

Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children, 17th century (ca. 1616–17)

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, 1598–1680)

Italian (Rome)

Marble; H. 52 in. (132.1 cm)

Purchase, The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, Fletcher, Rogers, and Louis V. Bell Funds, and Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, by exchange, 1976 (1976.92)

“This work is an old favorite on Art Hum tours of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is probably a collaborative work by Pietro Bernini and his far more famous son, Gian Lorenzo, one of the great virtuoso sculptors. Finished when he was only 18, this piece is a spectacular demonstration of skill. The visual interaction of the wild faun, plump children, a dog, a lizard, a tree trunk, vines, grapes and other fruit is so complex that it’s hard to know where to start looking. One thing you can do is just try to figure out where all the hands and feet are placed. Looking in this way pulls you around the statue, which is composed to make you move. Another way to enjoy Bernini’s art is to make a visual inventory of the different textures, all carved from marble: skin, hair, fur, bark, leaves, vines, fruit and more. Bernini, like a wizard, could transform stone into anything he liked.”

During the year Harrist spent in New York when he was on sabbatical from Oberlin, he went to see the New York City Ballet 65 times. It was the year of the Balanchine festival, and Harrist had discovered a love of Balanchine while in grad school at Columbia. “It changed my life,” he says of the first performance he saw. “I could tell instantly this was something marvelous I’d want to see again and again. It’s complicated, like paintings. It’s not something you can see once and think you’ve figured it out.” He became somewhat of an expert on choreography by self-study.

Harrist continues to expand his horizons within the art world. He has taken an interest in contemporary American ceramics artist Betty Woodman, for example. He continually goes to exhibitions — back in New York in September, in the 10 days between his return from the China conference and departure for a work trip to England, he was trying to squeeze in a gallery visit to see a show of works by Martha Armstrong, an artist he had never heard of. “I can’t wait to get down to Chelsea to see the paintings,” he says.

In 2010, Harrist encountered the abstract paintings of the late modern artist Roy Newell at a Chelsea gallery. But he didn’t stop at acquiring a work for his own collection; he returned to the gallery and made inquiries, then sought out Newell’s widow, Ann, to learn more. “She was so entranced with Bob, she gave him access to everything,” Hood says. Harrist curated an exhibition of Newell’s work at the Pollock Krasner House & Study Center on Long Island in 2014 and wrote the accompanying catalogue on Newell and his work.

“It was refreshing to do something outside of my normal field,” he says. “If you love art, you should love it all. You can’t be an expert in everything, but you should be interested in everything, and you should stretch yourself.”

Shira Boss ’93, JRN’97, SIPA’98 is an author and contributing writer to CCT. Her most recent article was “Building a Lifeline” (Summer 2015). She lives on the Upper West Side with her husband, two sons and two whippets.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu