|

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA FORUMEveryman in Times Square

Photo: Mel Rosenthal

Marshall Berman ’61 is the Distinguished Professor of Political Science at City College of New York and CCNY Graduate Center, where he teaches political theory and urban studies. His books include The Politics of Authenticity: Radical Individualism and The Emergence of Modernity; All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity and Adventures in Marxism. In his latest work, On the Town: One Hundred Years of Spectacle in Times Square (Random House, $29.95), Berman explores the symbolism of the famous crossroads in the flashing heart of Manhattan. “The signature experience … is being surrounded by too many in the midst of too much,” he writes. “Rem Koolhas calls it ‘Manhattanism,’ or ‘The Culture of Congestion.’ It is loved all over the world. It gives people a thrill, a rush, a power surge from being there.” In this brief selection from On the Town, Berman looks at one of the Square’s most famous images: “V-J Day, Times Square, 1945,” by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

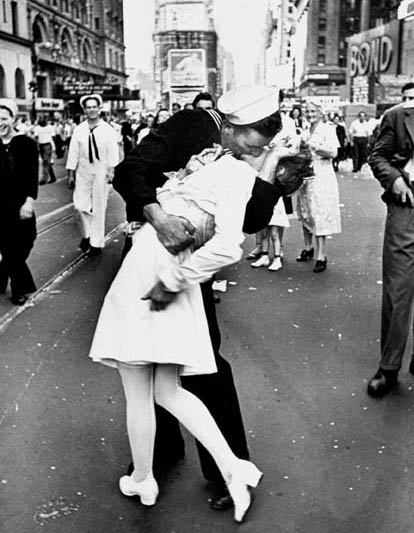

“V-J Day, Times Square, 1945” Photo: Alfred Eisenstaedt — Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

The two most famous people in the history of Times Square are anonymous. They are a man and a woman locked in each other’s arms. They were part of the enormous crowd that gathered in the Square on August 15, 1945, V-J Day, the day and night of Japan’s surrender and the end of World War Two. The PBS History of New York, produced by Ric Burns [’78], shows marvelous newsreel footage of that moment. When I first saw this footage in 2001, drawn from the National Archives, I was amazed I’d never seen it before, yet in another sense I felt I’d been seeing it all my life. It was a moment well choreographed. Around twilight, Mayor LaGuardia announced the surrender, and then, at a prearranged signal, after four years of blackout, all the lights in the Square went on. An earthshaking roar went up. A big band on a bandstand nearby (I have read it was Artie Shaw’s) began to swing, and thousands of men and women instantly started to dance, holding each other, jitterbugging, men throwing women into the air. The dancing is said to have gone on all through the night and past sunrise. Even when there was no music playing, couples moved to their own. As the camera pans the crowd, it is a thrill to see so many men and women who clearly are strangers embrace, hug and kiss, dance, squeeze the hell out of one another. Two of them, a sailor and a nurse, locked in a rapt embrace at the very center of the Square, became the subjects of a great photograph. It was taken by the German Jewish refugee photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, and it ran on the cover of Life magazine. They were also photographed at just about the same moment, from a slightly different (and less exciting) angle, by U.S. Navy photographer Victor Jorgensen; Jorgensen’s photo was reprinted in the next day’s New York Times. The sailor and the nurse and the crowd and the Square form one of the classic images of America and Americans in the twentieth century. It is a luminous moment of spontaneous, collective free love. Some of the fascination of this picture springs from its mystery: Who are this man and this woman? Together they form a sort of counter-monument to all our monuments to the Unknown Soldier: Instead of reminding us of the universality of death, they summon up an equally universal erotic life. Over the years, like claimants to a vacant throne, many men and women have put themselves forward as the real incarnations of this primal couple. In October 1980, Life ran a spread entitled “Who Is the Kissing Sailor?” The magazine compiled a kind of short list, ten men and three women. It reprinted their portraits from youth and from middle age, along with brief life stories and sound bites about what they did on the great day. Life tried, not very effectively, to assess their rival claims. Every one of the men (and one dead man’s brother) was certain he was the sailor, and wanted recognition from the world. The women tended to be more tentative and ironic: They said yes, they had embraced sailors in the Square, but so had many other young women who looked just like them. Eisenstaedt himself, who took hundreds of pictures that day, was of no help in sorting out the lineup. The men’s geographical and occupational spread — fish-seller, Rhode Island; school custodian, Illinois; history teacher, New Jersey; psychologist, California — made a fine Popular Front microcosm, reminiscent of so many real and imagined platoons and bomber crews of the Good War, and so many photo spreads in the prime of Life. In the 1990s, the Internet brought forth more candidates, and left reality as elusive as ever. Time magazine in 1996 ran an editorial on the controversy. The mystery could never be solved, they said, and it didn’t matter: “The real kisser remains Everyman.”

Jacket Design: Beck Stvan

Eisenstaedt’s photo is a perfect Renaissance perspective, with the foreground directly on the lower part of the bowtie, with big buildings converging diagonally toward the vanishing point, and a giant sign with a paternal figure promoting Ruppert Beer right on the point. This sailor and this nurse are surrounded by big buildings, by silver trolley tracks, by neon signs, and by the sky, but also by an assortment of other people. About twenty feet away there is a second sailor (and, in some croppings, a third), smiling on the couple. Another comment is suggested by the huge neon sign just to their right, which advertises BOND, then America’s biggest ready-made clothing store. Americans in 1945 all knew Bond Clothes, whether or not they wore them. It was one of those brand names like “5 & 10,” like “Life,” like “Times Square” itself, whose direct simplicity expressed America’s democratic and universal longings, the desire to bring us all together, like the Popular Front, “The House I Live In,” the Good War itself. The sign that proclaims the bond between this primal couple also highlights the more complex bonds that hold together the city, the country, maybe even the world. The other people in the picture are participants in the crowd’s festivities, but also, like ourselves, spectators of the couple’s embrace. They are both wearing uniforms, which mark them as “public servants” and separate them from the multitude of civilians (like ourselves) who surround them and whom they serve. His uniform is black, hers white. The contrast between them, sharpened by black-and-white film, heightens the clinch that binds them together. It also vests their unity with all sorts of symbolic resonance: man and woman, black and white, land and sea, war and peace, aggression and nurturing, yin and yang. All the great elements that define the picture — the couple, the crowd, the buildings, the signs, the sky — are composed so as to create a very satisfying whole. Actually, if we look closely, we can see it is a somewhat unstable whole. The two bodies are wound together at a precarious angle, tilting and twisting sharply downward. (In the Jorgensen photo, shot from about thirty degrees to the right, the tilt is even sharper.) If the sailor doesn’t get a stronger foothold soon, their momentum is going to throw them to the ground. Do they know they could crash? Are they worried? Not that we can tell. But if we think about this sailor, we will remember he has to be attuned to decks far shakier than any embrace on Broadway. The nurse herself does not look worried; she seems to be giving herself very freely to this embrace. She seems sure, and we can be pretty sure, that in a minute or so he will make some deft move that will stabilize them both. (“I guess he learned that sense of balance on board a ship.”) Even though, from what we can see of his face, he is just a kid, we can probably count on him to protect both of them — and so to protect the civilians, to protect us. * One thing that makes this picture so perfect is that, subliminally, it works so well as a parable of World War Two itself: “The Good War,” waged to protect both America and the world from real and powerful evil.

“Over the years, like claimants to a vacant throne, many

Eisenstaedt’s image shows us how, in the 1940s, the technology of street photography and the social structures of photojournalism gave photographers a power surge: They can open up all the ruptures and polarizations in our being, only to reconcile them and bring them together for all of us to see. It is hard to look on this tableau without nostalgic envy. At the same time, it is hard not to wonder, What planet was this? Can the gulf between this couple and ourselves ever be crossed? We’ll talk about it. The civilian and military people looking on are spectators to the embrace — as we ourselves are, so many years after — but also to the act by which the photographer is turning it into art. They may look like they aren’t doing much, but in fact their presence in the picture means a lot. They are like the chorus in old Greek comedies and tragedies (this picture looks more like comedy); they function not only as spectators of the action, but as commentators on it, and sometimes as participants in it. The Greek chorus was understood to represent the body of citizens, in a polis that was turning itself into the world’s first democracy. In an important sense, the comic and tragic actions were performed for these citizens; they couldn’t have been performed without them. They were the first rituals of democracy. The years 1944 and 1945 make up one of the great moments in the history of democracy, the moment of victory against the most murderous regime in history. (For once, thanks to Adolf Hitler, this language of hyperbole and propaganda told the truth.) It was a moment when, as victory unfolded, new rituals were born and made on the streets. Eisenstaedt’s photo is an active part of this creative process. It gives us the power to see how an act of totally “free love”, an embrace between strangers in the midst of a crowd of strangers, can be a communion of citizens. * Why can’t she be the one to make the move? She probably can, in the sense that she physically knows how. But in a year like 1945, she will assume that the man holding her knows how to lead, and she will let him, for their mutual comfort; however, if he can’t lead, she will know what to do. Her assumptions will be shared by any woman on the dance floor at the Astor Ballroom a hundred or so yards away, and by any modern single mother. Excerpted from ON THE TOWN by Marshall Berman. Copyright © 2006 by Marshall Berman. Reprinted by arrangement with The Random House Publishing Group.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||