Beth Willman ’98 wants others to make as many discoveries as possible from the largest astronomical dataset in history.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Beth Willman ’98 wants others to make as many discoveries as possible from the largest astronomical dataset in history.

Left: Willman in her office in Wilmington, Del. Right: The night sky dazzles over the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory as the Milky Way sprawls overhead. Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) can be seen just above the observatory.

JÖRG MEYER; H.STOCKEBRAND / RUBINOBS / NOIRLAB / SLAC / DOE / NSF / AURA

Beth Willman ’98 used to think about all the typical things a preteen in the ’80s might ponder: math homework, video games — and the fundamental nature of space and time.

“I remember sitting in my bed tent trying to figure out how far the edge of the universe is,” she says. “You know, just those existential questions you think about in middle school.”

From her childhood bedroom in a Pittsburgh suburb to her home office in Wilmington, Del., Willman still contemplates those perennial questions and how to answer them. She sits at her desk surrounded by plushie replicas of galaxies (including the one she found), an aluminum plate used to make a map of the universe and copies of The New York Times science section with space photos on the cover. They are evidence of a career steeped in discovery and her new mission to help others make their own breakthroughs.

Willman, an astronomer by trade, is the CEO of the LSST Discovery Alliance (LSST-DA). The Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) is a revolutionary undertaking that will, essentially, create the most comprehensive map of the observable universe ever. The new NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which sits atop a mountain just east of La Serena, Chile, has been specially constructed to house an enormous telescope and camera that will scan the sky for 10 years, generating an unprecedented amount of data: about 20 terabytes per night.

But the data is just the starting point for Willman. Her job is to make sure anyone with a good question to ask of LSST will be able to do so — whether they’re an undergraduate at a small university, a community college student or an early-career researcher looking for that first big breakthrough.

“Rubin’s LSST is going to create the conditions for democratizing science,” she says. “Brilliance is everywhere, not just at top research universities.”

Astronomy is one of the scientific disciplines at the forefront of the “big data” era. In the past, scientists had to count stars and objects by hand from photographs. LSST and other modern surveys scan and photograph the night sky, then convert the images into data points that will be housed in databases that make them more easily accessible. While the discovery of a galaxy or asteroid typically makes headlines, those findings wouldn’t be possible without the software and analysis tools needed to comb through massive amounts of data. And the more data there is, the more discoveries can be made — if one has the right tools and skills.

Historically, well-resourced institutions with large research capacities have had access to leading astronomical datasets, along with — crucially — the computational resources and engineering expertise needed to interpret them. By contrast, for students and faculty at less-resourced institutions, it can be difficult to analyze the survey data — no matter how promising the research question.

Willman views the LSST Camera before it was installed at the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

COURTESY BETH WILLMAN ’98

“What does it look like when you include 10 times more people in the scientific process, who wouldn’t have been included otherwise, and what results from that?” she asks. “It multiplies the science. Things will be discovered that wouldn’t have been discovered. I truly believe that because astronomy is on the leading edge of gathering open, well-curated data, other fields will learn from it.”

Despite her childhood fixation on the size of the universe, Willman wasn’t always an “astronomy gal,” she says. She was more interested in math and physics — her AP physics teacher even encouraged her to captain her school’s team in a local coding competition, giving her a taste of what it’s like to be a leader.

“I remember how great it felt to tell people about what the team had done, even though I’m pretty introverted,” Willman says. “And it felt great to stay late at school and push through debugging code. It’s a problem to solve and an answer to find; I just love that.”

Her plans changed when she was accepted to the College and received a letter from astronomy professor Joseph Patterson inviting her to join observations at an observatory in Chile. While her mind was blown that her application stuck out enough to warrant a personal letter, Willman still wasn’t sure astronomy was her thing. But the outreach made a lasting impression.

“Honestly, before I got involved with Columbia’s astronomy department, I thought astronomy was dumb — that it was just lists of planets and stars,” she says. “I didn’t appreciate that it was physics applied to the sky.”

A Rabi Scholar, Willman got involved in research on campus, but it wasn’t until she worked in famed astronomy professor David J. Helfand’s group that she found her place. “I always felt like he wanted me to be there, and I always felt better about myself after I left his office,” she says. “He asked me what I thought, and had the undergraduates and graduate students collaborate. He encouraged me to push myself intellectually.”

Helfand believes that Willman’s experience is one that arises naturally from having a non-hierarchical structure. Graduate and undergraduate students are on the same playing field, he says, and Willman’s opinions were respected and valued because they were equal contributions to the group — and possibly arrived the fastest.

“I used to tease her; she’s a very fast talker,” Helfand says.

The NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory team installing the LSST Camera on the Simonyi Survey Telescope in March 2025.

COURTESY BETH WILLMAN ’98

Willman says her galaxy proved pretty helpful for getting her name out there early in her career, but it isn’t something she’s still actively researching. However, she found something during her second postdoc that she still uses daily — a new focus.

“[It] gave me the chance to see how much I liked a holistic view of science,” Willman says. Rather than repeating the cycle of grant to research to publication, the experience enabled her to “see different parts of the machine. There’s fundraising, other people, the government and more. It really gave me a fuller picture.”

Willman took that desire for integrated science to Haverford College, where she spent seven years on the astronomy faculty. Rooted in the Quaker tradition, the college emphasizes community and collaboration across all facets of campus life, which helped Willman hone the cooperation skills needed to be a good leader. She continued researching ultra-faint galaxies with undergraduates, in addition to a stint as chair of the astronomy department; she says the latter prepared her to jump into leadership roles within large science collaborations.

“I had an understanding of the pieces that are needed to make something work,” Willman says. “And there was a lot of emphasis placed on listening to other’s perspectives, even if you disagreed. That characteristic of my leadership style was established early on, and it’s carried forward to the present.”

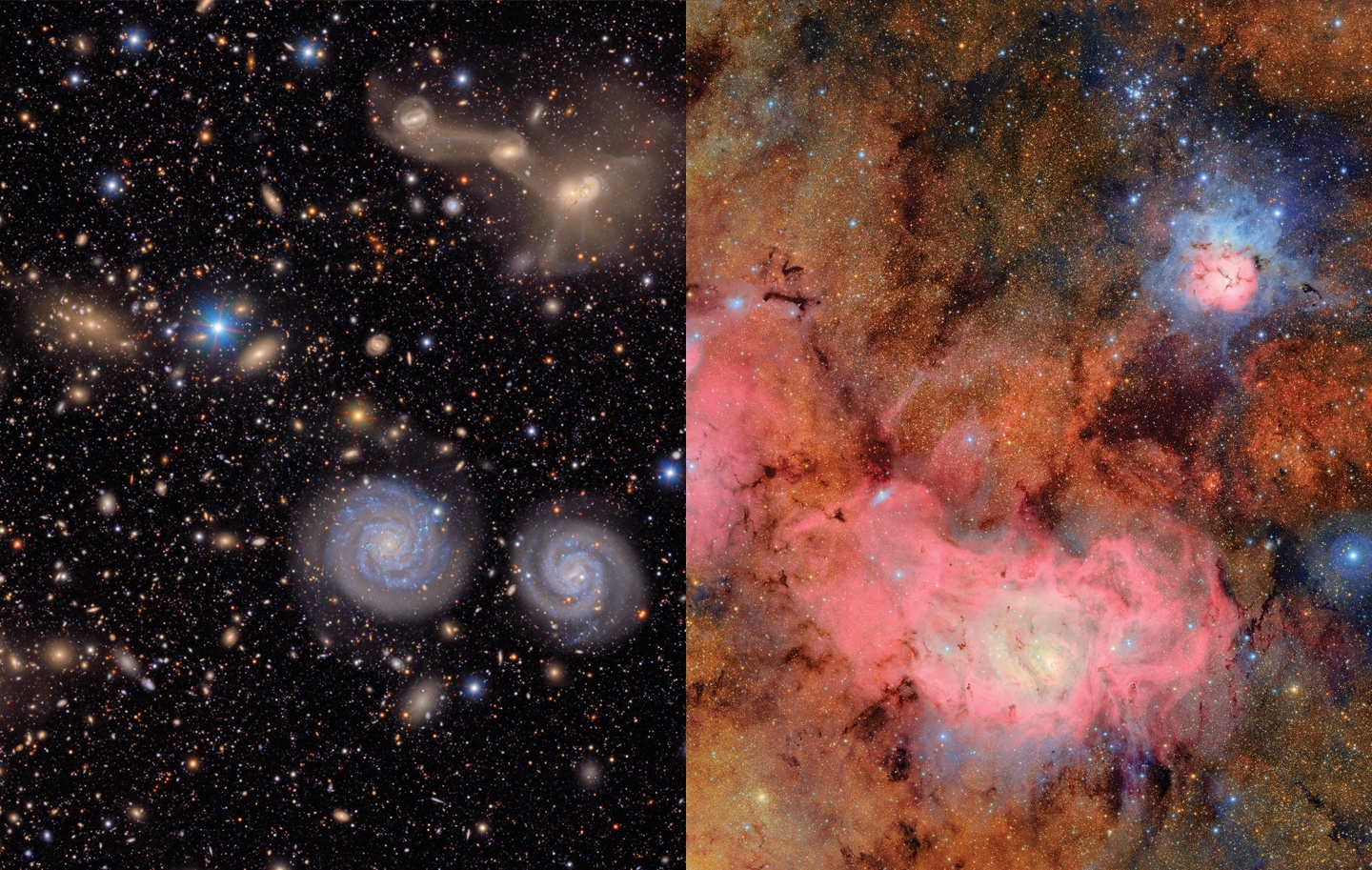

Left: A small section of NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s view of the Virgo Cluster. Two prominent spiral galaxies, three merging galaxies and galaxy groups near and far are visible.

Right: A view of the Trifid nebula (top) and the Lagoon nebula, which are several thousand light years away from Earth. The image combines 678 separate images taken just over seven hours, which reveals faint details like clouds of dust and gas.

NSF–DOE VERA C. RUBIN OBSERVATORY

At the Rubin Observatory in Chile, preparations for LSST are almost complete. Engineers are testing the telescope and scanning the night sky, checking to make sure that the enormous amount of data captured is as accurate as possible. In fact, the LSST will gather more astronomical data in just one year than all previous astronomical surveys. The key is in its digital camera, the largest ever built, encased in a telescope about as wide as a tennis court and capable of shooting an area more than 40 times the size of the moon. The LSST’s massive camera-telescope will take about 800 photos each night, meaning it won’t take long to capture a record number of images.

Meanwhile, Willman and her team are making preparations of their own. The survey is scheduled to begin in early 2026, with the first Data Release coming in 2027. It’s exciting, but also raises questions about who will have access to the tools and expertise needed to participate in groundbreaking discoveries using the largest astronomical dataset in recorded history.

“Once you can touch the data, what do you do with it? How do you get the software engineering skills to manipulate it? Do you have colleagues to collaborate with? How do you get the training to do this?” Willman asks.

The Rubin team took the first on-sky engineering data with the LSST Camera on April 15, 2025, shortly after darkness fell on Cerro Pachón.

RUBINOBS / NSF / DOE / NOIRLAB / SLAC / AU

“We are building partnerships between institutions that have a longer history of working with survey data as well as less resourced institutions to not just offer a spot at the table, but also to really integrate them into the system,” she says.

Case in point — Columbia and Rutgers, both member institutions of LSST- DA, have teamed up to bring CUNY into the fold, giving students and researchers at all three universities access to one another’s computing power, engineering and other resources. Willman says these kinds of partnerships are emblematic of LSST-DA’s approach to building a model of scientific collaboration.

She’s also developing programs to help astronomers streamline their work. Willman’s newest endeavor, Project Dovetail, is currently testing how contract software engineers might be hired to take on some of the more basic coding related to the survey data. (That way the work can be finished faster, delivering reproducible results and shared analysis software that much sooner for everyone to use.)

“You’ve got all of these engineers out there working from home since Covid-19 who just think astronomy is neat and want to spend 10 hours a week in the evenings doing this cool project,” Willman says.

In addition to membership dues from participating institutions, these exploratory programs and fellowships are made possible by private funders. Willman works to persuade other organizations of the importance of her nonprofit’s mission.

“If LSST-DA doesn’t do what it does, there are still going to be great discoveries, but we’re going to see that a lot of them come from the ‘haves’ — the institutions that have the computing capacity and software engineers on staff to do it,” she says. “But the other pathway is to seize the opportunity that has been created. This is a billion-dollar investment, and you can multiply the impact of that billion-dollar investment by getting the resources needed to do science into the hands of as many people as possible.”

Innovative programs like the ones LSST-DA is piloting are especially important in an era where traditional funding sources for science are not as reliable as they once were. Helfand, who has been on the finance and audit committee of LSST-DA, says that Willman’s leadership has been transformative and will continue to guide the organization as astronomy enters uncharted waters.

“She’s totally committed to supporting the member institutions and making sure they have access to resources,” Helfand says. “And I don’t just mean money. I mean data science experts and other tools to pursue their projects effectively. It’s going to be really important.”

Last June, Rubin released the first images captured by the telescope, and they’ve already led to an abundance of findings — including 2,104 new asteroids, stellar streams (which tell the stories of past galaxies) and more. It’s been a good test for Willman to identify what’s working and what isn’t ahead of the survey’s official launch. And she’s excited for all the future discoveries — she knows firsthand what it’s like to find something new. But she’s even more excited to see how many people can engage with and use this life-changing data.

“At this point in my career, I’m most proud of things like getting community colleges involved, or a new program to connect scientists with engineers,” she says. “These things that are impacting the practice of doing science are what will stick with me the most.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu