Breaking from customary cabernets, Massican’s Dan Petroski ’95 is changing the taste of the Napa Valley.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Breaking from customary cabernets, Massican’s Dan Petroski ’95 is changing the taste of the Napa Valley.

JÖRG MEYER

Petroski is equally blunt about the nature of his work: “People like to believe that [winemaking] is an art, it’s a craft, it’s a science, it’s a mystery. But when it comes down to it, it’s really manufacturing. No one likes to hear me say that.”

And yet. Does it get more romantic than Petroski’s decision to take a sabbatical from a successful magazine publishing career in order to apprentice at a Sicilian winery? Or his quest to find the just-right shade of blue for his brand, Massican — which took him from the Forbes Pigment Collection at Harvard to Pompeii, where he found his inspiration in a 2,000-year-old fresco? How about the label’s first wine, a white called Annia, named for Petroski’s mother?

Then there’s his belief in the transportive power of scent. “It’s so important to us as human beings, as animals,” he says. He talks about Annia’s aromatics, which evoke apples and citrus blossoms, honeysuckle and wet stones. For Petroski, it goes deeper. “I don’t even have to drink it anymore. I just smell it, and it takes me back through 17 years of what that wine tastes like and feels like. It moves me.”

Indeed, from that earliest sip in 2009 to today, Petroski has established himself as one of California’s most distinctive winemakers. In a region known for big, full-bodied reds, he is the only winemaker to produce exclusively whites. And not your typical West Coast Chardonnays — Petroski’s whites lean toward the style of the Mediterranean, “lighter, brighter, fresher” flavors, like those he enjoyed during his time in Sicily.

Early endorsement came when chef Thomas Keller selected Massican’s Sauvignon Blanc for his famed restaurant The French Laundry. (It stayed on the wine list for a decade.) Petroski went on to earn winemaker of the year distinctions twice, from the San Francisco Chronicle in 2017 and Vinepair in 2024. In 2022, Food & Wine declared him “Napa’s iconoclast” and awarded him laurels as a Drink Innovator of the Year.

In 2023, Massican was bought by Gallo, the world’s largest wine producer, with a portfolio of more than 100 brands. Among the deal’s key aspects, Petroski remained in charge of grape sourcing and winemaking.

Two other major buyers had approached him around the same time, he says, but they wanted to change too much, most notably by raising the price. “It was important to me not to make Massican more exclusive, more precious,” he says. “Gallo was the perfect fit because it was: Continue doing what you’ve been doing, and we can help you be more open to more people.”

Petroski grew up in Brooklyn, the youngest of four in a working-class family, raised by a single mom. A promising football player, he started hearing from recruiters in his junior year at Xavier H.S. and had even verbally committed to Lehigh in Pennsylvania before Columbia came calling. “I had no idea what the Ivy League was, just zero,” he says, adding that one of his teachers encouraged him to take a closer look. “They said, ‘Do you know what Columbia is?’”

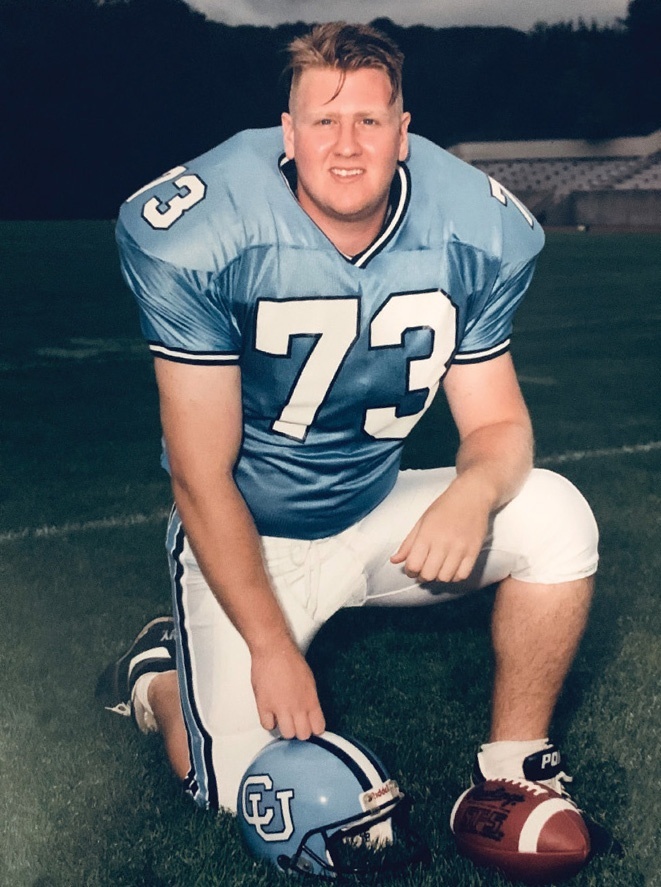

Petroski, an offensive lineman for the Lions, in his 1991 team photo.

COURTESY DAN PETROSKI ’95

Petroski graduated with a degree in history and vague ideas about what next. Following a brief detour to Detroit, he landed back in NYC at Sports Illustrated (SI). He says his College internships, especially at Interview, The Magazine Antiques and The New York Times, were crucial to opening that door, but his love for publications predated those experiences. “When I was a kid, we didn’t travel. I used to transport myself through reading magazines,” he says. “I was one of the founding subscribers of Condé Nast Traveler. Seeing pictures of people eating under canopies of trees in far and distant places — Italy, France, Greece, Spain — just engulfed my imagination.”

Petroski spent the next decade climbing the ranks at SI and its parent company, TIME; he also earned an M.B.A. from NYU. In 2005, Petroski had an opportunity to work on the weekend edition of The Wall Street Journal ’s Saturday publication. But he sensed the industry was changing and wasn’t sure he wanted to stay with it.

“I said, look, I love this place. If I leave here, I’m really going to leave, not just go to a competitor,” he says. Inspired by a TIME program that offered a sabbatical to longtime employees, he decided to create his own.

“I had a friend from business school who was Italian,” Petroski says. “We’d all visited him and his family in Italy just six months after graduation, in 2004, and we had a great time. So I said, ‘Why don’t you hook me up with some of your friends, I can work at a vineyard or something.’” Petroski laughs. “It was kind of really crazy.”

Crazy, but not wholly out of left field. Wine had become a hobby. “At TIME I had a credit card to eat at all the great restaurants in NYC,” Petroski says. “And no one knew anything about wine, so I decided to learn. I became the guy everyone would give the wine list to, because I would be able to find the value or the interesting story or the opportunity to drink well.”

By the time Petroski returned from a year at Sicily’s Valle dell’Acate winery, he was all in. He moved to Napa Valley, and in 2007 became cellar master at Larkmead Vineyards, one of the area’s oldest wineries. But even as Petroski continued his education, learning all sides of Larkmead’s business, he began to contemplate what his own operation could look like. Reds were the obvious choice — Napa is Cab Country; Cabernet Sauvignon grapes account for 54 percent of the region’s annual harvest. Merlot and Pinot Noir also abound. Yet Petroski found himself longing for something brighter.

“I had moved from one sunny Mediterranean climate to another and yet, here we were, drinking these big, bold, high-octane red wines. Even the white wines were rich,” he says.

“I was missing the Mediterranean style — these lighter, fresher wines that smelled of citrus and florals and tasted of salt air. Those are what we call white table wines, because of their food friendliness and ease of drinking. But they weren’t really part of the American consumer culture or palate.”

In 2009, Petroski set out to change that.

Petroski at Hyde Vineyard in Carneros, Calif.; he works with 17 farming families whose vineyards stretch across the region.

COURTESY DAN PETROSKI ’95

He started with the grapes. To produce the whites he dreamed of, Petroski needed to see what else Cab Country had to offer; his research uncovered varieties that had been farmed more than a century earlier.

“During the gold rush of the 1840s and 1850s, not only did Americans go west, but Europeans also came to go west,” Petroski says. “They heard about opportunity. And when there was no gold, they created agriculture.”

Left: Ribolla Gialla grapes at Vare Vineyard. Right: Sampling a glass at Massican Winery in Napa, Calif.

COURTESY DAN PETROSKI ’95; JÖRG MEYER

Today, Petroski works with 17 farming families whose vineyards stretch across northern California. Of the 10 grape varieties used for Massican, most are Italian, with musical names like Ribolla Gialla, Tocai Friulano and Falanghina. (The brand is named for Monte Massico, the Italian Campania region where his grandparents were born.) During harvest season — from early August to early October — he spends much of his time on the road, driving to different wineries and working with the teams in the cellars to make sure fermentations are going as planned.

“For me, making wine is understanding what you want to accomplish — what is the wine you want to put on the table? Then working your way backward,” Petroski says. “The idea informs everything, from what you plant; to where you plant it and what the weather is like at that vineyard; to how it is farmed; to when you harvest the grapes, and beyond. If you don’t have the vision, it’s difficult to find an easy pathway to an end.”

Petroski’s vision isn’t only for the wine in the glass. For him, Massican is also the expression of a lifestyle. There’s a magazine, a cookbook and 40 hours of playlists; in 2021, Petroski even created a virtual bar in the metaverse. “You can sit down and be taken away from the everyday and have a conversation with people from all over the world,” he says. “Part of the beauty of wine is that it creates a space, and we can help take you there.”

He is also committed to a broader stewardship, serving on the board of the Napa Valley Grapegrowers and of Napa Green, a global leader in sustainable wine- growing certification. “It really feels good to know that I stand shoulder to shoulder with farmers, and support 40,000-plus acres of agriculture in the Napa Valley,” Petroski says.

Practically and poetically, he believes the work weaves into a more enduring story.

“The California wine industry — although it’s been around for more than 150 years — it’s still very new,” he says. “We hear all about the amazing wineries and families in Europe who have been farming for 15, 16 generations. Here in America, it’s a much shorter history. So if we want this to continue, we have to give back, whether it’s how we farm, the decisions we make with our agricultural protocols or the support we give to the farm workers.

“That’s important to me, and to our industry — to make sure this continues to be here for future generations.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu