|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURESJohn Reeves Casts OffBy Jonathan Kelly '04 On an unseasonably warm February evening three years ago, a lanky forward, Joe Case '02, cocked his arms behind his head and launched a soft three-point shot — high and arched as if it flowed from a water fountain — that rained through the net and gave the Lions an insurmountable lead against Pennsylvania. As they had the night before, after the team’s victory over Princeton, students poured out of Levien Gymnasium at the game’s final buzzer and clambered across the dimly lit campus, regrouping upon the Low Library Steps. In the middle of this mass of incoherently chanting, light blue t-shirt-clad students stood Director of Athletics John Reeves. Reeves had cut short the standard post-game pleasantries for the second consecutive night in order to bask in the celebration. It had been 15 years since the men’s basketball team had swept Penn and Princeton at Levien, and the time had made the wins more gratifying. Standing like Sisyphus on top of his mountain, Reeves thought about how much fun Columbia students were having, and how happy he was to share the moment.

“I really felt their energy and excitement that night,” said Reeves, crossing his long legs in his office three years later. “The people I’ve always worked for were the undergraduate students.” Coming to Columbia when its athletics program was at a nadir, Reeves demanded — even though he didn’t always get — better facilities, as well as equity for women’s sports, and brought the program to a new level. Columbia athletics no longer is instantly associated with the football team’s notorious 44-game losing streak, or an ill-conceived and ill-fated gymnasium construction plan that helped bring the University to a standstill in 1968. While not all goals were achieved, Reeves, who retired on June 30 after 13 years at Columbia, leaves Columbia athletics in better shape than when he arrived, with solid prospects for continued improvement. “I think conditions are ripe for another step forward,” says former provost Jonathan Cole ’64, who oversaw the athletics department during Reeves’ first 12 years. “There’s a different set of values in the program today. There is an expectation that we are going to compete for championships on a regular basis.” Forty-two years ago, on the day after he married his wife, Janice, Reeves — who received his Ed.D. in physical education administration from Teachers College in 1983 — began his career in intercollegiate athletics as the men’s head soccer coach at Bloomfield (N.J.) College. His career would include stints at five institutions, with 34 years as an athletics director. Reeves came to Morningside Heights in August 1991 as Columbia athletics was crawling its way out of the doldrums. It was an institution still linked to a demoralizing losing streak in football, an institution drifting steadily from the legacies of Sid Luckman ’39, Lou Gehrig ’25 and Jim McMillian ’70. The search for an athletics director to replace the retiring Al Paul encountered the sort of hindrances that seemed to plague the athletics department with unsurprising regularity. None of the candidates who applied were up to snuff, and Reeves, an adept athletics director at SUNY Stony Brook, had withdrawn his name from the search, to the dismay of some committee members. Having garnered attention by elevating two sports to Division I status and opening a new indoor athletics facility, Reeves was happy at Stony Brook and reluctant to leave behind a tenured professorship.

The sanctuary of tenure, however, eventually paled next to the excitement of a new professional challenge. When the committee asked Reeves if he would reconsider, he agreed to apply, but on the condition that the director of athletics answer to the provost (who answers directly to the president), and no longer to the director of student affairs. “I’ve always been a guy who liked a challenge,”

Reeves says, reflecting on his decision. “I wanted Columbia

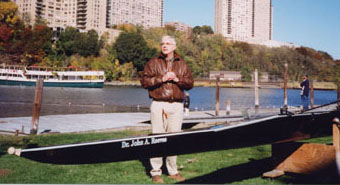

to be my last stop.” This presented a challenge for Reeves, not a problem. Devoutly positive, “problem” does not reside in his lexicon. “‘Challenge’ is a good word for Columbia,” says Reeves. “We’re land-locked, and we don’t quite have the endowment that Harvard and Princeton have, so we have challenges, and we never should deny that.” Reeves’ initial goal was to balance the budget and create innovative ways to generate revenue. The opening of the Dodge Fitness Center in 1996 provided much of the answer. By charging admission for the expanded facility, Reeves was able to bring in millions of dollars annually to enhance the physical education and athletics budget. Additionally, Reeves initiated a series of children’s instructional sports camps to supplement the department’s discretionary income fund. These camps have mushroomed, and now are attended annually by more than 250 children. In 1997, Reeves finally erased the athletics department’s $450,000 budget deficit. Under his direction and persistence, new funds made possible a number of new facilities. The Dick Savitt Tennis Center at Baker Field, completed in 2002, replaced an antiquated clay surface with cushioned hard courts under a modern dome. The stately 1929 Boathouse on the Harlem River, a new softball facility, the 6,000 square foot Aldo T. “Buff” Donelli Strength Room, the refurbished football and basketball locker rooms, a new Wien Stadium turf and a turfed practice football field are among the physical achievements that have taken place under Reeves’ watch. “John was a fighter for necessary resources,” says Cole, who played varsity baseball as an undergrad. “The facilities were in horrible condition. He had to overcome a legacy, and he carried out his plan with deftness and aplomb.”

However, attaining financial stability was less important to Reeves than elevating the credibility of Columbia athletics and expanding its offerings. In no way was this desire better manifested than in Reeves’ commitment to women’s sports. Of Columbia’s 29 varsity programs, 15 are women’s teams, and Reeves has been responsible for the creation of the last four: women’s lacrosse, field hockey, softball and golf. The women’s golf team began playing tournaments in 2003–04 and will attain full varsity status this fall. This commitment to women’s athletics at a school that only went coed in 1983 has transcended the creation of programs. After the graduation of Olympic swimmer Cristina Teuscher ’00, Columbia created a women’s sports endowment in her name. In February, Columbia hosted a successful black-tie gala commemorating the 20th year of the Columbia-Barnard Consortium and its continuing commitment to women’s athletics. One conspicuous blemish on Reeves’ legacy is Columbia’s failure during his tenure to win an Ivy League championship in either of the marquee sports, football and men’s basketball. In the past 13 years, the Lions have won or tied for 22 Ivy League championships and two national championships (both in men’s fencing). It’s the smallest number of Ivy titles among the league’s eight schools, and the majority of those championships have come in traditionally strong yet less popular sports such as men’s and women’s fencing, men’s tennis and, recently, women’s cross country. During Reeves’ tenure, the football and men’s basketball teams — programs that produce the most widespread alumni interest and following among students — recorded just two winning seasons each. In 2002–03, Columbia failed to win a single Ivy League game in either sport, a league first. “[Part of Reeves’] goal was to try to make sure that football and basketball received attention,” said Bill Campbell ’62, who played on the football team’s last championship squad in 1961, coached the Lions from 1974–79 and now is a successful businessman as well as a University trustee.

During the mid- to late-1990s, Reeves seemed to be succeeding. In 1996, the football team posted an 8–2 record, the team’s second winning season in three years. However, the Lions soon receded into the nether regions of the Ivy League under then-coach Ray Tellier, who had achieved noteworthy success as the head football coach during Reeves’ tenure at the University of Rochester. The football team never again reached .500, and the squandering of a three-touchdown lead to Lafayette on a dreary Saturday in October 2002 convinced some fans and alumni that Reeves had valued professional loyalty over success, charges that Reeves rejects. “In a sense, it’s a shame because Ray was the same coach he had been for years,” Reeves says of Tellier, who resigned after a 1–9 season in 2002 but continues to work in the athletics department. “Unfortunately, he lost six games in the last 10 minutes in his last year.” Criticism of Reeves’ loyalty to his coaching staff came to a head, however, in the wake of men’s basketball’s disappointing 2001–02 campaign. One winter removed from the upsets of Princeton and Penn, a talented and senior-laden team finished the season with a disappointing 4–10 Ivy League record. The letdown prompted letters from alumni — some printed in CCT — criticizing Reeves for not replacing then-head coach Armond Hill. Reeves defended Hill, his record and his performance. Although Reeves maintains that part of the 2001–02 team’s collapse was due to the nagging injuries of sixth man Mike O’Brien ’02, he admits that his adamant response was a mistake, and that it cost him some credibility. However, Reeves does not regret standing up for his coach.

“Until you make a decision that you are going to make a change, you defend the people around you,” says Reeves. “You know what they’re going through, you know what their challenges are, and they don’t need a leader who doesn’t support them. I wrote a letter about where our coach was coming from and where he was going. I would do it again because I believed in the coach. The alumni just understand wins and losses.” Gerald Sherwin ’55, former president of the Alumni Association and chairman of the men’s basketball alumni advisory committee, understands as well as any alumnus the constraints under which Reeves worked and recognizes that success is not measured solely in wins and losses. However, he also unapologetically observes, “As long as you keep score, you might as well win.” As the head of physical education and intercollegiate athletics, Reeves ran a varied program. For 13 years, he likened his job to a pyramid starting with physical education instruction at the base and ascending to intramurals, club sports and, at the summit, intercollegiate athletics. When he arrived, a large part of his job was building this pyramid out of sand when, Cole says, “There were people at the University who disdained athletics.” Now the cries to win may be a harbinger of things to come. “Winning has been elevated in importance, and that is a good thing because unless you have that desire among alumni, students and administrators, it’s hard to hire and retain coaches and give them the resources to win,” says Reeves. “What has come is a raising of the bar in areas where we were given the green light to spend more on recruiting and coaching resources.”

“A lot of alumni are interested in wins and losses, especially in the major sports,” says Sherwin, who believes that the tide may be turning. “Unfortunately, we haven’t had too much of that recently, but maybe we will with [men’s basketball coach] Joe Jones and [football coach] Bob Shoop.” Jones and Shoop were among Reeves’ final hires, and will play a critical role in determining the tenor of his legacy. While neither posted winning inaugural seasons, both manifested remarkable promise. Shoop’s team upset Harvard and Princeton for the first time since 1978 and finished at 4–6, including 3–4 in the Ivy League. Jones’ team climbed from 2 to 10 victories, capped by a double-overtime win over a Yale team coached by Jones’ brother, James, that resulted in Columbia students storming the court en masse. Wandering the crowd that night was Reeves, struck with a case of déjà vu, recalling his happiest moment at Columbia: the 2001 sweep of the so-called “Killer Ps.” The ascendancy of both programs will hinge greatly on the ability of Shoop and Jones to recruit successfully. In order to bring in the best athletes, however, Columbia may need to reconsider its recent prioritization of athletics. In the 1980s, five acres of Baker Field were sold to make room for a hospital. In 1993, plans for a high-rise athletic facility atop the Dodge Fitness Center were abandoned, and, most recently, a plan for an aquatics center at 122nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue was rejected and the site instead was used for the Law School and the School of Social Work. Another site long coveted by Athletics, the undeveloped southeast corner of Broadway and 120th Street, is expected to be devoted to a new science tower.

Reeves repeatedly petitioned the administration to build on behalf of athletics, and believes that job must be continued by his successor. “I think a fresh voice will have more success,” says Reeves. “Each time you go someplace else, you can achieve more for a certain period of time. For Columbia, it is the perfect time for someone else to come in.” For those familiar with the daily operation of the athletics department, Reeves’ legacy is clear. “He has taken all our programs and moved them forward,” says Associate Athletic Director Jacqueline Blackett, who served on the search committee that hired Reeves. “Our students and athletes have been able to know their athletics director, which is unique at a Division I school. Working with John has been like working with family.” In the last year alone, Reeves has proven that Columbia can compete for the top coaches and athletes. President Lee C. Bollinger, who did not find losing palatable at the University of Michigan, has changed the reporting structure so that athletics now reports directly to his office. “John Reeves has set the direction for the program,” says Josie Harper, director of athletics at Dartmouth. “I know now that President Bollinger will make it happen.”

“I think it’s a new era, where athletics has been given a high priority,” Reeves said wistfully in April, shortly after it was announced that the field hockey team, which has had little success in recent years, was going to be coached by USA National Field Hockey team captain Katherine Beach. She was Reeves’ final hire, his final imprint on the department. “I wanted to continue to carry a banner that says ‘We’ll go as high as we can to find the best coach,’ ” says Reeves. “If I did it for men’s sports, I am certainly going to do it for women’s.” In his office, Reeves moves to his computer to point out the screen’s wallpaper: two empty chairs staring off the dock of his waterfront property in the Poconos. The author of six books and numerous articles, Reeves has plans to pen a book on the new directions of intercollegiate athletics, but he admits there will be distractions. “I want to read, write, travel and fish,” he says, “but skip the first three if the fish are biting.” Jonathan Kelly ’04 graduated with a B.A. in history. He is pursuing a career in journalism and is a fact-checker and researcher at Vanity Fair.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||