|

|

|

|

|

|

|

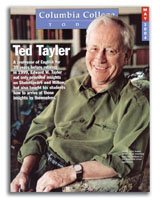

LETTERS TO THE EDITORTed Tayler

Many thanks for David Lehman ’70’s excellent profile of Ted Tayler, my favorite Columbia professor [May 2004]. I wonder if other students of Tayler remember him asking us what his favorite fish was. According to him, the tails of male sticklebacks turn red when they fight. One morning, a great number of them were found belly-up in the aquarium following the passage of a large red mail truck. The sticklebacks, it seems, had apparently mistaken Art for Life. With puzzlers like this, delivered in his measured pace, Tayler embodied the role of Zen master for a generation of literary acolytes. The Sons of Ben would have understood perfectly. Dan Gover ’66 The Ted Tayler bandwagon appears filled to overflowing. I’d like to claim at least a toehold on the running board by dint of having been assigned to Tayler’s first Humanities A class, which convened on a Thursday morning in late September 1960 in the building now called Dodge. I was among the first to hear the “Don’t get nicotine stains on the mat” anecdote, clearly spurious even then but just as clearly an indelible piece of Taylerana. I subsequently enrolled in a 17th-century survey course taught by Tayler, and in his first senior seminar, which met at 2 p.m. on Friday, a time that could be loved only by someone who loved teaching. I had arranged a hedonistic schedule in the last semester of my last year, with classes on only Tuesdays and Thursdays, so that I could play as much tennis as possible. Tayler knew it, and I think delighted in the inconvenience to me. One warm spring Friday, showing up in a pair of madras Bermuda shorts, I was greeted by Tayler’s dry imitation, perhaps, of that old Amherst wrestling coach: “Nice of Oster to show up on his way to the Hamptons.” Jerry Oster ’64 After the passing of so many of my professors, I was thinking about who I wanted to speak with and thank without waiting for a life cycle. I immediately thought of Professor Tayler. As many of his former students stated in the article, “He changed my life.” I know that sounds trite, but it is true. I came to Columbia convinced of my career path — political science, government, leading to law school. A funny thing happened on the way to the library: I had to take Humanities, and fate shone on me by putting me in the section taught by Professor Tayler. I do not like admitting it, but until that class, I hated to read, and I was anxious about any writing assignment. I had a number of junior and senior high school English professors who never made our work more than a stroll down the checklist of clichés. My writing was passable, but certainly not much above average. With his “go ons” and his challenges and his ability to “tayler” teaching to each student, he changed everything. I became an English major; I became a student of the period Professor Tayler taught; I took every course he had (explaining to my friends outside of Columbia that it was possible to take a full-year course on John Milton and read everything he wrote because, like that mountain, it was there); he became my faculty adviser; he helped me get the assignment to teach the discussion group on Shakespeare; and he did a lot more. One day, Professor Tayler was perceptive enough to notice that I had gotten almost a terminal case of unrequited love sickness. He insisted we go out for coffee and gave me the best advice on dealing with relationships I have received to date. While I was in New York for college and graduate school, I stayed in touch. Then when I moved to Washington, D.C., I lost what had been a special chapter in my schooling. The CCT article brought it all back and has inspired me to get in touch with him. As we are now in our 50s, many of our teachers are getting on. It is good to remember to say thanks to them when we can do it directly and in person. Abbe Lowell ’74 David Lehman ’70’s article about Professor Tayler highlighted how he influenced a generation of Columbia undergraduates who went on to distinguished careers in poetry, literature and academia. Although I didn’t, let me tell you how Professor Tayler influenced me. In 1966, I was a senior, majoring in zoology, who had already been accepted to medical school. My friend, John Seybold ’67, an English major, told me that I shouldn’t miss taking a course with Tayler, so I asked his permission to sign up for his graduate seminar in Milton. I explained to him that I didn’t know anything about Milton, and hadn’t taken any literature courses other then Bentley’s course in modern drama and Dupee’s course in modern poetry. I asked him if he thought that I would be able to do the work for his course. Tayler laughed quietly and told me to register; thus started the most intellectually challenging and stimulating time of my life. Every week, I found myself sitting next to Tayler at a conference table along with nine brilliant English majors. Tayler would lead a lively discussion with them, which I would struggle to follow. Toward the end of the hour, he would turn to me and say something like, “Galinsky, explain to these fellows how Milton uses time before and after the Fall.” I would say something that probably made no sense to anyone in the room, but Tayler would smile, nod sagaciously and ask me another question. He would then continue asking me questions until, under his tutelage, I finally composed a coherent answer. I’m not sure, but I think that he was using me to summarize the lesson that he wanted to communicate to all of the smart people in the room. Then he would announce that for the next meeting, we would have to write a paper on Milton’s use of metaphor. I would spend all of my time for the next week trying to come up with some idea about Miltonian metaphor, because I knew that he was going to ask me to explain everything at the end of the hour. In my field of geriatric medicine, my patients and I grapple with terrible problems. Frequently, we find ourselves confronting challenging situations in which the answers to life’s questions do not come easily. I would like to think that Tayler taught me about how to search for truth and meaning, a process that transcended the question about Milton that he posed. He taught me something about struggling with life and death in a meaningful way. Professor Tayler, thank you for allowing me to register for your course. David E. Galinsky M.D. ’67 To the CoreThank you for your provocative May 2004 issue. I found Timothy P. Cross’ article on the evolution of Lit Hum especially engaging and rewarding during this celebration of Columbia250. During my College years, it was fashionable to malign Lit Hum as the obsolete “Greatest Hits of the Mesozoic Era, Vols. I and II.” Butler Library was draped with banners of alternate lineups of authors to be studied in Lit Hum, authors whose gender and race, as well as their works, were intended to better represent the history of literature and speak to modern students. Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Cicero, Vergil? They were the Dead White Guys, and the Lit Hum syllabus was ever up for debate. There are, I can safely say from the heart of commercial Manhattan, worse and more hype-driven canons to which one can devote one’s energy. Check out midtown’s frenetically erected monument to the new, hip and trendy, the AOL Time Warner complex at Columbus Circle. It is midtown’s burgeoning agora to McKim, Mead and White’s Morningside Heights Acropolis. Can’t abide Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles? Try Hugo Boss, Eileen Fisher and (even the formerly timeless and classic but now MTV’d–up and precious) Coach. More expensive than an Ivy League education! More hype than Columbia250! Filled to bursting with worshippers! We live in an era obsessed with age and hell-bent on fresh starts, a culture that feeds on the latest, newest and most “in” via hundreds of channels. We watch people on TV get their homes, wardrobes, love lives and bodies gutted and done over. Even a Core course must face the overarching values of the modern and up-to-date; reading is not “in,” and what most people do read (and watch and listen to) seems to be geared toward how to look, dress, act and smell like the latest 20-year-old pop icon. Especially at a time such as this, the Lit Hum syllabus could seem a relic and fall under attack. The traditional and classic always will be challenged by the modern and iconoclastic. So be it; the debate over the Lit Hum syllabus is worthy and ultra-Columbia. It also may be beside the point of the Core Curriculum. My favorite delayed-reaction Columbia moment (similar to those set up by Professor Edward Tayler and described in David Lehman ’70’s article in the May issue) at Columbia was inspired by the inimitable Professor Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41 near the time of President Lee C. Bollinger’s inauguration. In true Columbia spirit, I was armed with skepticism about the subject and prepared to be nonplussed by the celebrated scholar. Many then-undergrads in attendance, laboring under the heavy reading loads of the Core, fidgeted and averted their glazed eyes toward the evening traffic on Amsterdam, but succinctly, elegantly, de Bary demonstrated himself to be, like the Core itself, not about his considerable hype, and far beyond it. De Bary brought to life a history of teaching and learning at Columbia. Months later, I had my Eureka! feeling and was able to put the Core into proper perspective. Great Books? Great Thinkers? The most important thinker in the Core is each College student, and the thoughts (“Great” or not) the Core ultimately exhorts us to examine most closely are our own. Homer, Herodotus (or do today’s Lit Humsters call him H-Rod?) and the rest of the Dead White Guys? They still have plenty to say about such perpetually modern issues as the ugliness of war and the tyranny of self-aggrandizing second-generation despots, and I don’t regret a page. Their names are literally carved in stone, but their greatness was and perpetually is a matter of personal evaluation by each of us — and only a starting point. As for them and the educators who have maintained the tradition of an ambitious discussion-oriented literary program for Columbia undergraduates, semper sint in flore. Amy Ann Hamilton ’92 I read with interest Timothy P. Cross’ article on the evolution of the College’s Literature Humanities course. The article revived a long-forgotten memory: The astonishment and, not to put too fine a point on it, sheer disgust I felt as a College sophomore in 1979 at the absence in the syllabus of any text representing Romanticism. Lovers of foolish consistencies are, I am sure, delighted to see that, a quarter-century later, the spirit of Irving Babbitt, T.S. Eliot, Yvor Winters and other despisers of Romanticism remains vibrant and well. Kevin Shelton ’82, ’83 GSAS

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||